The Making of Old Town Alexandria

A walk through Old Town Alexandria is a stroll through Colonial America. The cobblestone streets, brick houses, and various shops and pubs all combine to transport visitors to quaint, rustic, 18th century United States. But the picturesque Old Town we know today didn’t just happen naturally. Rather, it was planned (and re-planned!) repeatedly, in response to America’s burgeoning historic preservation movement, mid-century urban renewal efforts and a lot of involvement from local citizens.

By the 1920s and 1930s, America was at the peak of the Colonial Revival movement, a period marked by nostalgic preservation of all things historic in reaction to the rapidly modernizing world.[1] George Washington’s home, Mount Vernon was a popular tourist destination and a major highway was built to run from the mansion through Alexandria, and into D.C. Alexandria city planners knew the flow of people passing through their city was a huge potential source of income. City planners had the idea of turning Alexandria into a historic district, in order to capitalize on tourists brought in by the highway. It was a solid plan. Alexandria had a plethora of historic buildings and plenty of famous figures in its past. Plus, officials were very familiar with the success that Williamsburg had enjoyed by turning back the clock to colonial times, so they had high hopes.

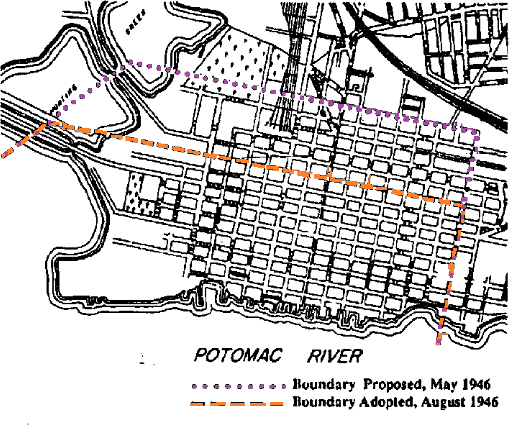

Initially, preservation efforts focused mainly on the residential buildings within inner Alexandria. In 1946, Alexandria City Councilman Paul Delaney drafted the Charleston Ordinance, a piece of legislation modeled after Charleston, SC, which was one of two historic districts in the U.S. at the time (the other was New Orleans). The ordinance was revised several times but finally passed, officially creating Old Town Alexandria, the third Old and Historic district in the United States.

Under the Charleston Ordinance, efforts had been focused on protecting Alexandria’s historic buildings in its original residential neighborhoods, which lay inland. Meanwhile, the nearby commercial area, located along King St, was in a state of decline.[2] By the 1960s, the King St area was filled with empty stores and derelict buildings. There were some residences there, too, in which people lived on top of another. One finding reported that many of the residences lacked basic plumbing and sewage. “I’ve got no sink, no bathroom, no bath, no nothing,” said one resident at the time.[3] Another resident said, “the rats come in like mad”[4] into his house. The planning director labeled the area “a breeding ground of crime,” adding “the police and health departments consistently report more calls to this area than any other.”[5] Clearly, the state of this area was a problem for city officials, whose Old Town district was attracting a lot of new residents and visitors, just as hoped. Something had to be done. Enter urban renewal.

The first proposed urban renewal plan was the Beggs Plan of 1960, urban planner John Beggs of New York City.[6] This plan called for the demolition of 20 blocks in Alexandria, including a number of structurally sound buildings and historic buildings. “This means that some houses that are still good houses will have to be sacrificed ... some people in Old Town won’t like that,” said the urban renewal coordinator, Stuart Morrison, at the time.[7] That turned out to be an understatement. The plan was wildly unpopular — so much so that the meeting of the Alexandria City Council to discuss Beggs’ proposal was described by the Alexandria Gazette as “the most riotous aggregation of indignant citizens since the war of 1812.”[8] One Alexandrian at the meeting with the last name Beggs stood up to announce that, just to clear the record, he was of no relation to John Beggs who had proposed this plan.[9] The plan was voted down unanimously.

As Donald King, former Chairman of the Community Development Committee said later, “Beggs took the easy way — tearing down everything.”[10] Alexandria needed a more creative plan.

The Alexandria City Council thought they had achieved just that in 1963 when they approved the Gadsby Commercial Urban Renewal Plan. This plan had been created by city planners under the supervision of historic preservationists, who were there to ensure the preservationist agenda was kept alive during redevelopment.[11]

The plan, slated at $50 million,[12] was broken down into three phases, each of which would redevelop a different section of King St. The first phase would redevelop two blocks — the block where Gadsby’s Tavern was located (where the plan derived its name) and the following block, where City Hall was located. The second phase of the project included the south side of the 300, 400, and 500 blocks of King St, and the north side of the 500 block of King St. Phase III would develop the 600 block of King St.[13]

In 1964, Phase I commenced. The area in front of City Hall was developed into a large plaza, called Market Square, which was a recreation of the original farmer’s market from 1753.[14] A block over, Tavern Square was developed around Gadsby’s Tavern, a historic building that was preserved.[15] Other buildings weren’t as lucky. The Belvoir hotel was located right next to the Gadsby Tavern and stood on foundations that had dated back to 1792. No one realized the hotel was quite so old until it had already been torn down.[16] Another building lost to renewal was Arell’s Tavern, believed to be a local meeting place for George Washington and other leaders.[17] Problems only increased as the plan moved into Phase II.

This phase consisted of large scale demolition of older commercial structures along King Street to replace them with modern structures. But before demolition began, those with property in the area challenged the city’s right to demolish the buildings. Property owners refused to sell their buildings to the city to be torn down and they said the City Council’s declaration of the area as blighted in order to obtain the right to tear them down was an “arbitrary and capricious” attempt to take private property.[18] Almost simultaneously, citizens of Old Town belonging to various preservation groups raised their voices against bulldozing buildings in this area because of their historic value.[19] E.K. Van Swearingen said that the city was, “willing to make a fast buck at the expense of historic monuments.”[20] Preservationists also weren’t thrilled with the resulting architecture of Phase I, calling the buildings a “monument to Mammon,”[21] which was entirely against the colonial feel they hoped for.

The preservationists took their fight to court, along with property owners, but both cases were promptly shut down by an Alexandria judge.[22] Demolition occurred, and Phase II was completed in 1981. But the change in public opinion was palpable. When a storm blew over a partially renovated building at one point during construction, a local said, “See, even the Lord’s against urban renewal.”[23] When it came time to begin phase III, Alexandrian citizens wanted nothing more to do with the urban renewal project. They were in luck — this phase was never completed due to a lack of funding.[24]

Footnotes

- ^ Mary Miley Theobald, “The Colonial Revival,” Colonial Williamsburg (2002), http://www.history.org/foundation/journal/summer02/revival.cfm.

- ^ Stephen J Craig-Smith and Michale Fagence, Recreation and Tourism as a Catalyst for Urban Waterfront Redevelopment: An International Survey, (Westport, CT: Praeger Publishing, 1995), 42.

- ^ Everard Munsey, “Alexandria Homes Show Years of Neglect: Slum Residents Suffer With Cold, Filth, Vermin,” The Washington Post, Oct. 24, 1960.

- ^ Mechlin Moore, “Alexandria Weighs Code As Step in Urban Renewal,” The Washington Post, Nov. 25, 1957.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ted Pulliam, Historic Alexandria: An Illustrated History, (San Antonio, TX: Historical Publishing Network, 2001), 60.

- ^ John Neary, “Alexandria Given $18 Million Plan for City Renewal,” The Evening Star, July 19, 1960.

- ^ Ted Pulliam, Historic Alexandria: An Illustrated History, 60.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Victoria Stone, “300 Cheer Demise of City’s Renewal Plan,” The Washington Post, July 27, 1960.

- ^ Ted Pulliam, Historic Alexandria: An Illustrated History,60

- ^ Peter S. Diggins, “Alexandria Stars $50 Million Urban Renewal Job Next Week,” The Washington Post, August 2, 1965.

- ^ Ted Pulliam, Historic Alexandria: An Illustrated History,61.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Gretchen M. Bulova, Images of America: Gadsby’s Tavern, (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2015), 61.

- ^ Ibid., 62.

- ^ Walter B. Douglas, “Alexandria Renewal Claims Historic House,” The Washington Post, August 6, 1964.

- ^ Maurine McLaughlin, “Alexandria Group Pledges Fight to Save Old Houses: Downtown Renewal Proposal Termed Modest Monument to Mammon,” The Washington Post, September 14, 1967.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Demolition In Old Town Still Upheld,” The Washington Post, December 27, 1967.

- ^ Maurine McLaughlin, “Alexandria’s Urban Renewal Opposed: Phase III in Trouble Legal Action Election Issue Other Projects,” July 10, 1966.

- ^ Gretchen M. Bulova, Images of America: Gadsby’s Tavern, 61.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)