A New Time for the 9:30 Club

“On the corner of Ninth and V Streets NW, the big construction dumpsters are filling up with rubble, as the inside of the big yellow brick building that sits there gets transformed. Rumors have been flying for weeks that it’s going to be the new 9:30 club, the granddaddy of the city’s alternative music spaces.”

--The Washington Post, November 3, 1995

The rumors were indeed true. The famed 9:30 Club was gearing up to move from its downtown F Street location (which interestingly shared the exact alleyway with the Ford’s Theatre that John Wilkes Booth used to escape after killing Lincoln), to its new home at 815 V St. NW, formerly known as the WUST Radio Music Hall. As Eric Brace wrote in The Washington Post in 1995: “If you’ve ever been to the 9:30 Club, you know its strengths and weaknesses. You could say it’s an intimate place, full of atmosphere and character. Or you could say it’s a small, smelly club, with a big pillar right in front of the stage, and that there’s no place to comfortably sit and watch the bands.”[1]

Both descriptions of the 9:30 were true. While the club was known as a destination for alternative music in the 1980s, it had just as strong a reputation for being cramped and dirty (with everything from a stench to rats). With the club’s 1996 move, owners Seth Hurwitz and Rich Heinecke, hoped to create a larger and cleaner space, while keeping all of the 9:30’s atmosphere and character.

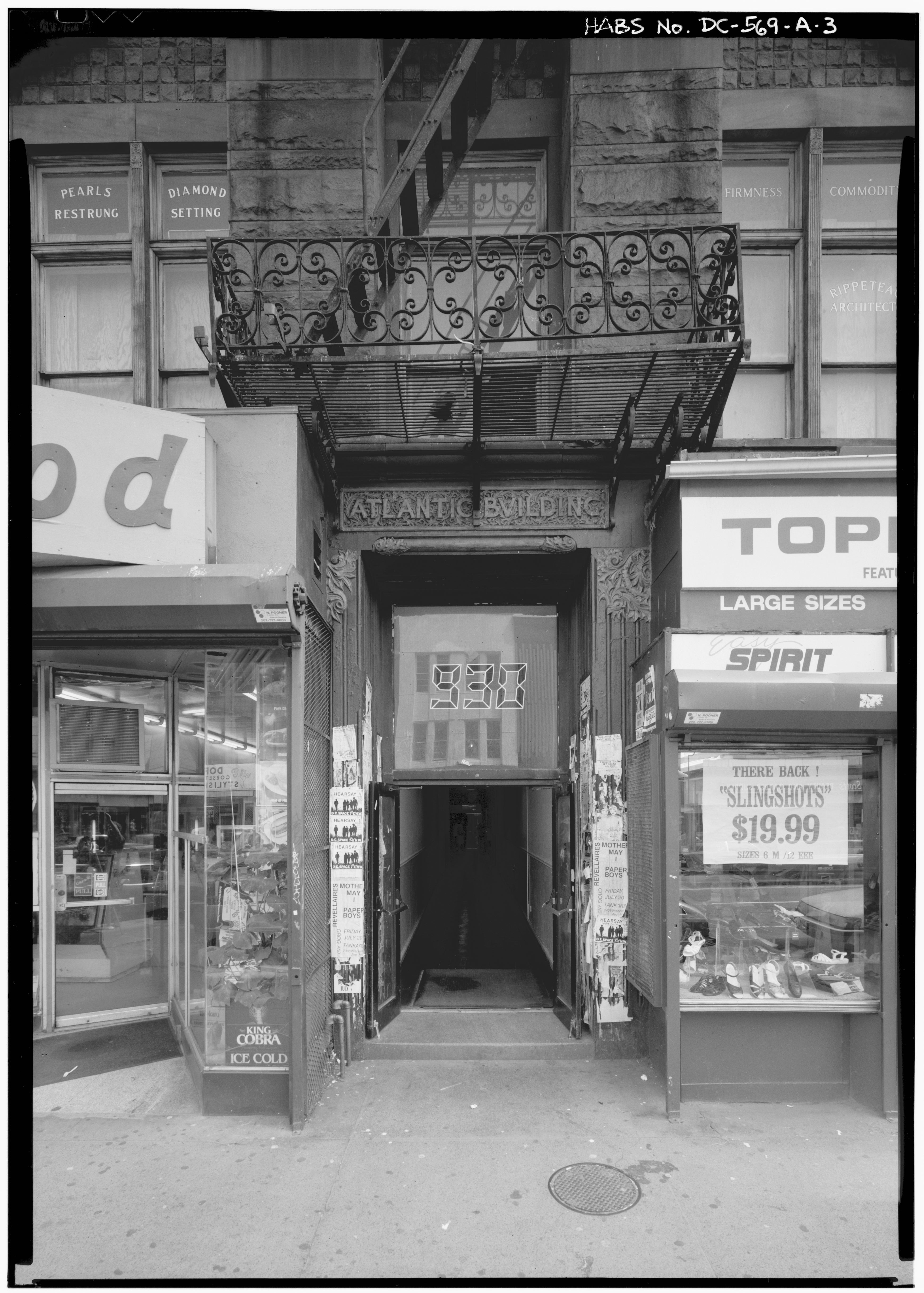

The tiny, L-shaped 9:30 Club, located in the historic Atlantic Building on F Street NW, was originally founded in 1980 by John Bowers and Dody DiSanto. For the next six years, DiSanto helped the club to grow, and took to booking “new music, preferably of an experimental, avant-garde or performance art nature.”[2] By as early as 1981, however, it became obvious that in order for the club to survive, it would have to appeal to pop culture ideals.

DiSanto worked frequently with Seth Hurwitz and Rich Heinecke of the It’s My Party (I.M.P.) concert promotion company to book up-and-coming bands that eventually became some of the biggest names in new wave and punk. In 1986, Hurwitz and Heinecke bought the 9:30, and continued to grow the club as a landmark for alternative music.

In fact, the club’s notoriety grew so much, that the tiny 199 capacity space on F Street became too small for an establishment that had hosted The Red Hot Chili Peppers, Fugazi, R.E.M., the Police, and even Nirvana.[3]

Hurwitz and Heinecke had been thinking about moving the club since buying it in 1986, and after a six year search for a new property, they chose the WUST Radio Music Hall building located at 815 V St. NW, and purchased it for $700,000.[4] Prior to housing WUST, the V St. building was the home of Duke Ellington’s, a music club owned by the famous jazz pianist and composer who was a Washingtonian himself.

“A no-nonsense, industrial-looking structure on the outside, the building had two obvious advantages for its new user—size enough for nearly 1,000 fans (compared with 300 or so downtown), and a high, column-free central spaced framed on three sides by balconies. It was, in other words, very like a bare-bones theatre that could be handsomely adapted into a music club.” [5]

Seth Hurwitz explained that a new moveable stage would allow for the space to be “anything from a coffeehouse to a concert hall. It’s designed to be small and expand, not as a big place that will get small as an afterthought.”[6] The architect and designer for this versatile concert space, was Neal Duncan.

Duncan was no stranger to the 9:30 Club. As he recalled later, “Before I got married I was there every night it was open. Five nights a week, say, for 10 years—thousands of hours, millions of decibels.”[7] Duncan even met his wife at the place, and unsurprisingly felt a deep connection with the club. One night at the club, he approached Hurwitz and offered his architectural services, saying “I love this place, and I’m an architect, and if you’re ever thinking of moving, I’d like to help out.” Duncan added, “We made a loose arrangement. I would give them advice on new spaces, with the idea that when the time came I’d get the job.”[8] When the time came, Duncan worked closely with Hurwitz and Heinecke throughout the six year property search, and even did schematic designs for six different places before they unanimously agreed on the Radio Music Hall, and started a $1.3 million building project.[9]

Keeping his emotional connection to the 9:30 in mind, Duncan transformed the Radio Music Hall Building into Hurwitz and Heinecke’s vision for a versatile space. The new club featured lights and speakers on an overhead track that allowed them to move with the moveable stage, a three-level balcony free of view-blocking columns, and brand new dressing rooms with “showers, fax machines, [and] personal viewing balconies to watch the stage without joining the riffraff.”[10] (Nice dressing rooms were a universal request of every band to come through the original 9:30 Club who found the spaces dirty and uncomfortable). Once a new sound-system, kitchen, and four bars were up and running, the reborn 9:30 Club opened on January 5, 1996 with a “thundering, grandiose meld of punk, metal and art-rock” concert from the Smashing Pumpkins.[11]

According to the Washington Post, “both the Smashing Pumpkins and the 9:30 Club were on their best behavior” that opening night.[12] The Pumpkins played from 9 p.m. until midnight with only one short break, and started with an acoustic set in which they sat down and wore pajamas. “Those who were not enthralled by the show had plenty of postmodern architectural mysteries to investigate, such as the way the walls in the balcony contrast wire mesh covering with faux-classical columns.”[13] Any disinterested concert-goers, however, were engaged with the Pumpkin’s longer, and much louder second set. Billy Corgan, lead singer for the Pumpkins, even yelled “we’re not tired!” during their second set of encores.[14] When the show finally ended, the new 9:30 Club had been inaugurated in a way that was most appropriate for its prior 15 years of history.

Although some hard-core 9:30 regulars felt that the new space lacked the intimacy of the original club, the V Street location was able to provide a unique concert experience of its own, while keeping the grunge charm of the original club. Although a little part of the old days was lost in the move, the change was, for the most part, seen as a positive one, and music fans have been enjoying bangin’ concerts at the 9:30 ever since. Perhaps Peter Zaremba of The Fleshtones put it best:

“For the Fleshtones, the new 9:30 club doesn’t have the same feeling of home that the original did. It’s a really fine, fine place to play, and they still treat bands really well. But it’s a different scene, a different audience. It’s just not 1980 anymore. But that’s a good thing.” [15]

Footnotes

- ^ Brace, Eric. 1995. “Time For A New 9:30: OUT THERE.” The Washington Post (1974-Current File); Washington, D.C., November 3, 1995, sec. On The Town. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Harrington, Richard. 1995. “The 9:30 Club: The Time of Their Lives.” The Washington Post (1974-Current File); Washington, D.C., December 31, 1995, sec. Arts. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ “Meet Me at 9:30: A History of DC’s 9:30 Club.” 2016. Washington.org. July 25, 2016. https://washington.org/visit-dc/930-club-history-washington-dc.

- ^ “Welcome to the Club: An Oral History of D.C.’s 9:30 Club on Its 30th Anniversary.” 2010, April 18, 2010. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/04/16/AR20100….

- ^ Forgey, Benjamin. 1996. “A Big Hand For the New 9:30: An Old Fan Orchestrates Rock Venue’s Makeover.” The Washington Post (1974-Current File); Washington, D.C., January 5, 1996. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Brace, Eric. 1995. “Time For A New 9:30: OUT THERE.” The Washington Post (1974-Current File); Washington, D.C., November 3, 1995, sec. On The Town. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Forgey, Benjamin. 1996. “A Big Hand For the New 9:30: An Old Fan Orchestrates Rock Venue’s Makeover.” The Washington Post (1974-Current File); Washington, D.C., January 5, 1996. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Welcome to the Club: An Oral History of D.C.’s 9:30 Club on Its 30th Anniversary.” 2010, April 18, 2010. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/04/16/AR20100….

- ^ Forgey, Benjamin. 1996. “A Big Hand For the New 9:30: An Old Fan Orchestrates Rock Venue’s Makeover.” The Washington Post (1974-Current File); Washington, D.C., January 5, 1996. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Jenkins, Mark. 1996. “9:30: Just the Place For Smashing Pumpkins.” The Washington Post (1974-Current File); Washington, D.C., January 6, 1996, sec. Style. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Welcome to the Club: An Oral History of D.C.’s 9:30 Club on Its 30th Anniversary.” 2010, April 18, 2010. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/04/16/AR20100….

![“The restored Lincoln Theatre, once a premier African-American entertainment venue, Washington, D.C.” (Photo Source: The Library of Congress) Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. The restored Lincoln Theatre, once a premier African-American entertainment venue, Washington, D.C. United States Washington D.C, None. [Between 1980 and 2006] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2011636050/. “The restored Lincoln Theatre, once a premier African-American entertainment venue, Washington, D.C.” (Photo Source: The Library of Congress) Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. The restored Lincoln Theatre, once a premier African-American entertainment venue, Washington, D.C. United States Washington D.C, None. [Between 1980 and 2006] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2011636050/.](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/17856v.jpg?itok=KiWAaHRq)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)