"Say your say, do your thing, stand up and be counted": The First National Black Deaf Advocates Conference

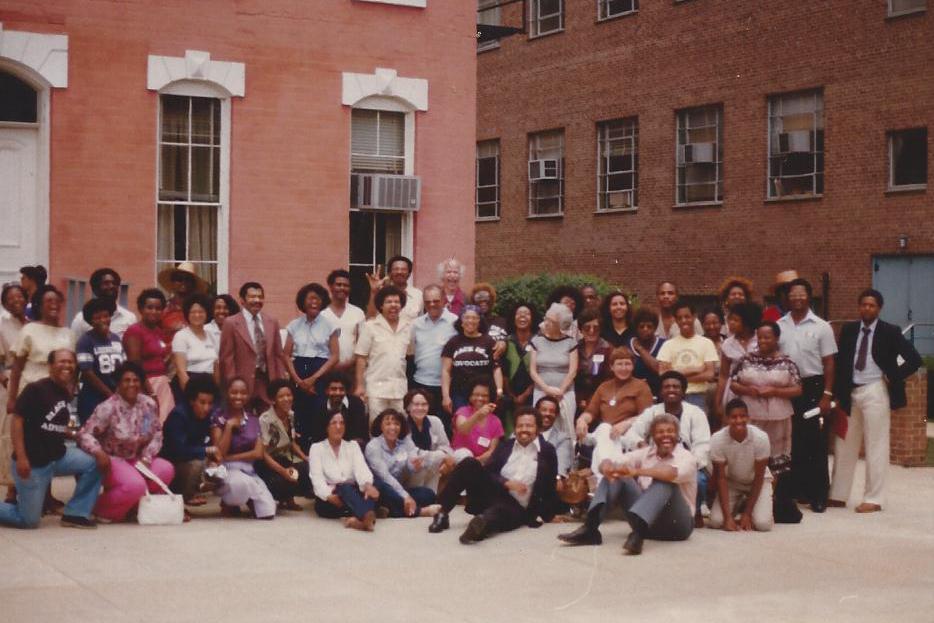

If you wandered onto the campus of Howard University on July 25, 1981, you would have been met with quiet. Not the quiet of a campus empty of students for the summer, but the quiet of over 100 people conversing in American Sign Language about the importance of bolstering the Black Deaf community.

These people—everyone from teachers to social workers to academics to political leaders[1]—were part of a momentous event in Black Deaf history: the first conference of what would soon become a nationwide organization called the National Black Deaf Advocates.

Planning for this conference had been in the works for over a year. Leaders in the Black Deaf community from DC and around the country had noticed a lack of Black leadership in Deaf organizations and were determined to change that. A promotional flyer for the conference read, “Feeling lonely? Frustrated?? Left Out??? Isolated????” and encouraged potential attendees, “Now is your chance to find out what’s happening; to say your say, do your thing and to stand up and be counted.”[2]

The flyer was a not-so-subtle acknowledgement of what many in the Black Deaf community knew all too well: Racism had just as insidious an impact on Deaf communities as hearing ones, and the history of being Black and Deaf in America was marked with exclusion. The largest national Deaf group, the National Association for the Deaf (NAD) prohibited Black membership until 1965. Even after it opened its doors to Black people, the group remained largely white.[3] The same was true for Gallaudet, the country’s first Deaf university. It did not allow Black students until 1952 and their numbers remained low into the 1960s.[4]

In the vacuum created by this exclusion, other groups emerged to serve the needs of Black Deaf people. These ranged from gatherings on street corners to formal nonprofits offering a wide array of services and events.[5] But by 1980, local Black Deaf leaders in DC wanted more. They partnered with community members from across the country to present the idea for a national Black Deaf organization to the National Association for the Deaf.[6] NAD expressed support for the idea,[7] though they were skeptical as to why a separate national Black Deaf organization was necessary.[8]

Organizers Ernest Hairston and Linwood Smith knew exactly why it was necessary. Without an organization focused on Black Deaf people’s specific needs, “it would be the same old story—token Black person joins the organization and is a good old fellow, outmaneuvered by sophisticated white members, smiling all the while. It is time for a different approach.”[9]

That different approach began with the weekend-long conference at Howard, which leaders branded “The Black Deaf Experience.” The event was a first for the Black Deaf community: A geographically diverse meeting of the minds focused entirely on Black Deaf issues.[10] Participants flocked to the conference from the DC area, nine US states, and even the countries of Kenya, Nigeria, and Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo).[11]

From its conception, the conference was intended as a space where people did not have to compartmentalize their Black and Deaf identities like they may have done in other areas of their lives. As Lottie Crook, one of the conference’s organizers, explained, “it grew out of a need of Black deaf individuals and their families and friends to better inform themselves and their communities about what it means to be both Black and deaf in America today.”[12]

The event had three stated goals:

To better inform ourselves and the community about being both Black and deaf in America

To identify and examine the social, economical, educational, religious, political, and health issues and their impact on the Black deaf community

To formulate some strategies and problem solving techniques that participants can take back to their communities and use.[13]

On the first day of the conference, attendees gathered in a Howard classroom for a welcome address by Dr. Jay Chunn, the Dean of the Howard School of Social Work and Marion Barry, the mayor of DC. Then the group sang and signed “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” the “Black national anthem.”[14] This opening ceremony encapsulated many themes of the conference: mutual support, education, and working hand-in-hand with the Black hearing community. Hairston and Smith reflected that, “A recurring statement at the conference was the need for Black people to work with Black people, in most instances because of the need for empathy, roots, role models, and special understanding, especially in the areas of mental health and social services.”[15]

Over the course of the weekend, workshops held at the conference highlighted six major issues: education, family, social services, health and mental health, employment, and interpreting. Attendees could choose from workshops, group and panel discussions, and Q&A sessions. There were also informational sessions about the latest developments in the Deaf community, such as understanding Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act and how to use the newly invented telecaptioner, a device that generated captions for home TV sets.[16] Speakers and workshop leaders included leaders in the Black Deaf community, Howard professors, and representatives of organizations that served the Black Deaf population, such as the Division of Mental Health Programs for the Deaf at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital.[17]

After each day of events, attendees spilled out into the broader Washington community, into restaurants, bars, and hotels. They forged friendships and hatched plans, dreaming of a world where their full selves would be acknowledged and welcomed.[18]

The conference also provided a way to bridge gaps within the Black Deaf. Chuck Williams, one of the conference’s organizers, recalled, “During that time in 1981 and forward… many of them [the attendees] were Black Deaf people who were from the South and we didn’t realize they didn’t go to integrated schools at that time. So, we came and learned about them and so did they… Their signs were unique. I learned so much but they smiled and we dressed the same and their communication was a little bit different.”[19]

Another attendee, Sheryl Emery, recalled meeting scholar and conference organizer Ernest “Ernie” Hairston at the conference. “I grew up in the Midwest and never had the opportunity to meet other Black Deaf role models, so Ernie and other people I met there was the first time I’ve seen professional, educated Black Deaf men who were working and talking about history and their responsibilities. I mean, that blew my mind.”[20]

By the conference’s end, people like Williams and Emery were proof that the conference’s goals of informing and strengthening the Black Deaf community had been achieved. That 1981 conference was a successful test run for what was to come. During the conference, organizers planned the creation of a national organization, the National Black Deaf Advocates (NBDA), which was officially founded the following year.[21]

Today, NBDA continues to serve the Black Deaf community, hosting the same annual conference that began in 1981. The organization addresses causes such as Black Deaf education, police violence, fostering leadership among Black Deaf women, and creating scholarships and mutual aid funds.[22] In addition, NBDA and its passionate members remain instrumental in holding other Deaf groups accountable and making a space for Black Deaf people in the Deaf community.

Footnotes

- ^ Conference speakers list, MSS 168, Box 1 Folder 1, National Black Deaf Advocates Collection, Gallaudet University Archives.

- ^ “Black Deaf Advocates Urge You to Attend…,” MSS 168, Box 1 Folder 1, National Black Deaf Advocates Collection, Gallaudet University Archives.

- ^ Benro Ogunyipe, “Deaf Culture Through the Lens of History,” Described and Captioned Media Program.

- ^ Rezenet Tsegay Moges, “From White Deaf People’s Adversity to Black Deaf Gain”: A Proposal for a New Lens of Black Deaf Educational History,” Journal Committed to Social Change on Race and Ethnicity 6, no. 1 (2020): 83.

- ^ Ibid., 37

- ^ “District of Columbia Area Black Deaf Advocates, Inc.,” 1991, MSS 168, Box 16 Folder 13, National Black Deaf Advocates Collection, Gallaudet University Archives.

- ^ Susan Teeter, “Need of Deaf Blacks Recognized,” The Cincinnati Enquirer (Cincinnati, OH), Jul. 6, 1980.

- ^ Ernest Hairston and Linwood Smith, Black and Deaf in America : Are We That Different? (Silver Spring, MD: T.J. Publishers), 1983, 48.

- ^ Ibid., 48.

- ^ Ibid., 37.

- ^ “District of Columbia Area Black Deaf Advocates, Inc.,” 1991, MSS 168, Box 16 Folder 13, National Black Deaf Advocates Collection, Gallaudet University Archives.

- ^ Letter from Lottie Crook to Jay Chunn, MSS 168, Box 1 Folder 1, National Black Deaf Advocates Collection, Gallaudet University Archives.

- ^ Hairston and Smith, 47.

- ^ “The Black Deaf Experience Wrap-Up,” Jun. 26, 1980, MSS 168, Box 16 Folder 12, National Black Deaf Advocates Collection, Gallaudet University Archives.

- ^ Hairston and Smith, 47.

- ^ “The Black Deaf Experience Wrap-Up,” Jun. 26, 1980, MSS 168, Box 16 Folder 12, National Black Deaf Advocates Collection, Gallaudet University Archives.

- ^ Conference speakers list, MSS 168, Box 1 Folder 1, National Black Deaf Advocates Collection, Gallaudet University Archives.

- ^ Restaurant recommendations list, MSS 168, Box 1 Folder 1, National Black Deaf Advocates Collection, Gallaudet University Archives.

- ^ Sheryl Emery, Ernest Hairston Chuck Williams, interview by Deaf News, February 26, 2021, transcript and recording, Deaf News, dailymoth.com.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “District of Columbia Area Black Deaf Advocates, Inc. 10th Anniversary Celebration Program: History of District of Columbia Area Black Deaf Advocates, Brief Chronology by Lottie Crook,” 1991, MSS 168, Box 16 Folder 12, National Black Deaf Advocates Collection, Gallaudet University Archives.

- ^ “Programs and Advocacy,” National Black Deaf Advocates.

![504 Button Bright yellow protest button created by the American Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities (ACCD). The pin reads in black block-lettering: "Handicapped Human Rights, Sign 504, ACCD." [Source: National Museum of American History]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/504%20Button.jpeg?itok=yiaSjVx2)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)