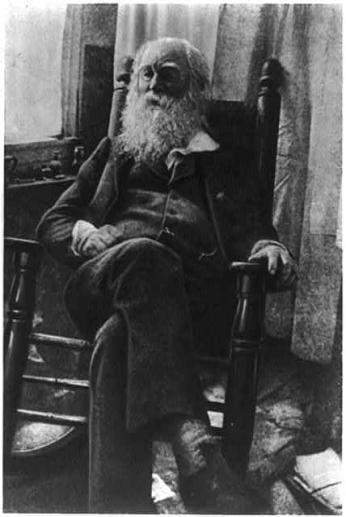

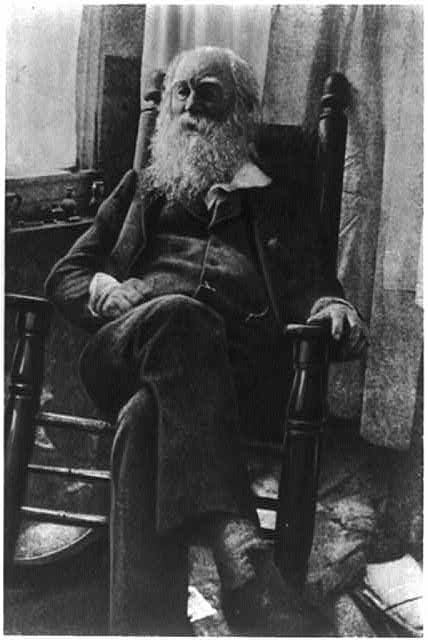

'The real war will never get in the books': Walt Whitman Chronicled the Civil War From Washington Hospitals

When Walt Whitman first rushed to Washington in the winter of 1862, the trip had nothing to do with poetry.

It was Dec. 16 — nearly two years into the Civil War and seven years into Whitman’s poetry career — when the New York Herald listed a “First Lieutenant G.W. Whitmore” among the troops killed or wounded in Fredericksburg, Va. The misspelled listing was referring to George Whitman, Walt’s brother, who had enlisted in the Union Army in 1861.

Walt left immediately to search Washington’s hospitals. The poet would stay in the city for the next 11 years.

Back in New York, the rest of the Whitman family waited on a telegram. After a few days of silence, Jeff Whitman, another brother, was getting anxious. “We are all much worried at not hearing anything from you,” he wrote to Walt. “I know you will spare neither pains nor anything else to find him, and I do hope that dear brother George is not seriously hurt.”

For two days, Whitman searched for his brother among the city’s wounded. But George was not in Washington; in fact, he had never left Fredericksburg. When Whitman found him there, he was alive and well. A small cheek wound — the injury that had placed George on the lists in the New York Herald — had already healed. When Whitman returned to the city, he wrote his sister, Martha, that he would be happy if he could only be with her and get a steady job in New York.

But on the journey back to Washington — a train ride followed by a boat ride up the Potomac — Whitman found himself among wounded soldiers traveling north. And at some point, he started talking with them, asking how he could help. By the end of the trip he was sending letters to parents, brothers, and wives, updating them on the status of their boys. “On the boat I had my hands full,” he later wrote.

It was around this time that Whitman found himself drawn to the city’s wounded, and he visited the hospitals daily. His services were small ones — he would talk with the wounded, try to cheer them up, and play games like twenty questions. He prided himself on stopping to read the details of each patient’s injury as he walked down the rows of beds. When he described his encounters in his letters and journals, he always remembered names.

The time had come, he decided, to find a way to support his work financially — he was, after all, an unpaid volunteer with no other source of income. And so the poet wrote to one of his earliest admirers: Ralph Waldo Emerson. When Whitman first published Leaves of Grass, he had sent a copy to Emerson. And while the first edition of the poetry collection had been unsuccessful, it impressed Emerson, who was already a prominent essayist and poet. Whitman told Emerson he wanted to apply for a position in Washington, and asked him to write letters of introduction to the Secretary of State and the Secretary of the Treasury.

“It is pretty certain that, armed in that way, I shall conquer my object,” read the letter. “Answer me by next mail, for I am waiting here like ship waiting for the welcome breath of the wind.”

Emerson replied, “If you wish to live in that least attractive (to me) of cities, I must think you can easily do so.”

Whitman took a part-time job at the Army Paymaster’s Office. He developed a routine: After work, he would relax, bathe, change his clothes, and eat dinner. Then he would pack a bag of gifts — paid for with donations raised by George and friends back home — and head to the hospitals. Most days, he would visit with the wounded for four or five hours. Sometimes he stayed all night.

The Civil War proved to be a sort of revelatory experience for Whitman. The wounded soldiers, with their silent composure in the face of suffering, had a certain type of strength that Whitman saw as a reflection of their country’s character. They had a quiet nobility about them, and the poet found it beautiful that ordinary Americans could exhibit such strength. “I now doubt whether one can get a fair idea of what this war practically is, or what genuine America is, and her character, without some such experience as this I am having,” he wrote.

And as Whitman discovered this sense of nobility within his country, he thrived on the conviction that he was a part of it. The small comforts he provided each day became a source of pride for him. In his letters and journals, he often wrote about the individual soldiers who particularly depended on him (“not a soul here he knew or cared about, except me”) and the meticulous care with which he went about his hospital duties (“I have come to adapt myself to each emergency, after its kind or call, however trivial, however solemn, every one justified and made real under its circumstances”).

When he wasn’t talking with the soldiers, or bringing them gifts, he was reading them poetry — but never his own. He would read from Shakespeare and the Bible, and never mentioned that he was a poet himself. He encouraged the soldier to write letters, and when asked, he wrote the letters himself. Often, when a soldier didn’t make it, Whitman wrote to the parents.

By Whitman’s estimate, he made over 600 hospital visits over the course of the war, visiting between 80,000 and 100,000 wounded.

“The Hospital, I do not find it, the repulsive place of sores and fevers, nor the place of querulousness, nor the bad results of morbid years which one avoids like bad s[mells]—at least [not] so is it under the circumstances here—other hospitals may be, but not here,” he wrote to Emerson. He added, “I desire and intend to write a little book out of this phase of America.”

Whitman would publish that book, called Memoranda During the War, in 1865. And in that same year, he published Drum Taps, a collection of poems about his experiences in the Civil War. In one of those poems, he writes, “Beauty, knowledge, fortune, inure not to me—yet / there are two things inure to me; / I have nourish'd the wounded, and sooth'd many a / dying soldier; / And at intervals I have strung together a few songs, / Fit for war, and the life of the camp.”

Later, Whitman would call the Civil War “the very centre, circumference, umbillicus, of my whole career.” Reflections on his time in the hospitals are peppered throughout his poems and prose works.

And yet, he never believed that any sort of writing would paint a clear picture of what he had witnessed.

“The real war will never get in the books,” he would write in Specimen Days. “Its interior history will not only never be written — its practicality, minutiæ of deeds and passions, will never be even suggested.”

The war and the soldiers that filled Whitman’s literary life, according to the poet, could never be truly, wholly represented in writing. The Whitman in Washington was a self-described “sustainer of spirit and body in some degree, in time of need” who never once mentioned he was a poet — he believed, it seems, that writing was a secondary role.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)