1989: Bringing Down D.C.'s Drug King

April 15, 1989 – almost “go time.” A joint force of DEA, FBI and D.C. Police officials had spent nearly two years building their case against the District's largest drug network, and a series of coordinated raids had been carefully planned for the next day.

But then rumors began to circulate that word of the impending raids had leaked out onto the streets. Worried that their opportunity would be lost, authorities hurriedly put their plan into action, early.

At 5:30pm, officers arrested Tony Lewis at his home in Arlington. A few hours later, they nabbed the big prize – alleged ring leader Rayful Edmond III – at his girlfriend's house in the 900 block of Jefferson St., NW. With the two biggest targets in custody, officials launched searches at more than a dozen other addresses in the District and Maryland, including Edmond's grandmother's rowhouse at 407 M Street, NE, which was thought to be the headquarters of the operation.

And what an operation it was.

Edmond allegedly supervised a wholesale and retail illegal narcotics business that brought in 1,700 pounds of cocaine a month from California and employed more than 150 people. At the height of the District's drug epidemic of the late 1980s, business was good – very good. The group generated as much as 2 million dollars a week and controlled perhaps 50% of the cocaine trafficking in the city.

The inner workings of the Edmond's network sound like the script from a movie or perhaps a certain HBO series.

Much of the cocaine was purchased from the Los Angeles-based Crips gang, which had a direct connection to a Colombian drug cartel. Couriers from Edmond’s network would travel to California carrying suitcases full of money – often 3 million dollars or more. After making the purchase, the couriers would return to D.C. by plane or in rented vans filled with drugs.

As The Washington Post described it, “The bags of cocaine allegedly were distributed to street sellers by lieutenants with names like 'Mad Dog,' 'Whitey' and 'Fat Cheese.'…. After selling the crack, the sellers turned in their proceeds to lieutenants…. Walkie-talkies were used so the lieutenants, sellers and lookouts could communicate and ensure that the sellers would not be robbed.”[1] The inner circle was a close-knit family organization.

Any time police came by on patrol, lookouts shouted warnings. “Oller-ray! Oller-ray!” Pig-Latin for “roller,” which was street-slang for patrol car. Trip wires and debris were strewn across alleys to help dealers avoid arrest.

Associates spoke in code to disguise their dealings. Street sellers were paid $400-800 per week but could make as much as $5000. “Mules,” who transported the drugs from L.A., were paid as much as $1,000 per kilogram that they brought to the Washington area. Other couriers were paid for delivering cash to Los Angeles for drug purchases.

Enforcers armed with automatic weapons kept away rival dealers and killed those who infringed upon Edmond's territory, which was centered around the open air drug market at Orleans Place, NE but spread to other parts of the city. Over 30 homicides during 1988-89 were attributed to clashes between Edmond's network and rival groups.

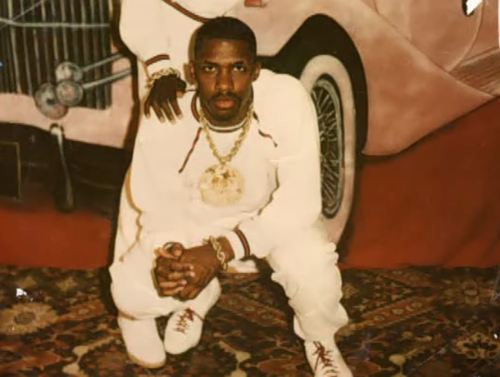

For his own protection, Edmond himself kept a certain amount of distance from the day-to-day dealings of his organization. He was not handling the drugs or cash on the street. But the flashy lifestyle the business afforded him – with his fleet of cars, designer clothes and expensive jewelry – certainly made an impression. As the Post put it, “Edmond was something of a walking advertisement for his organization.”[2]

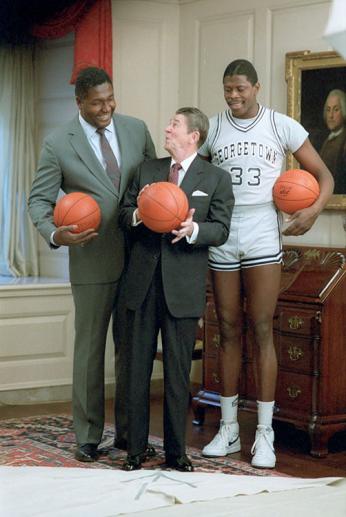

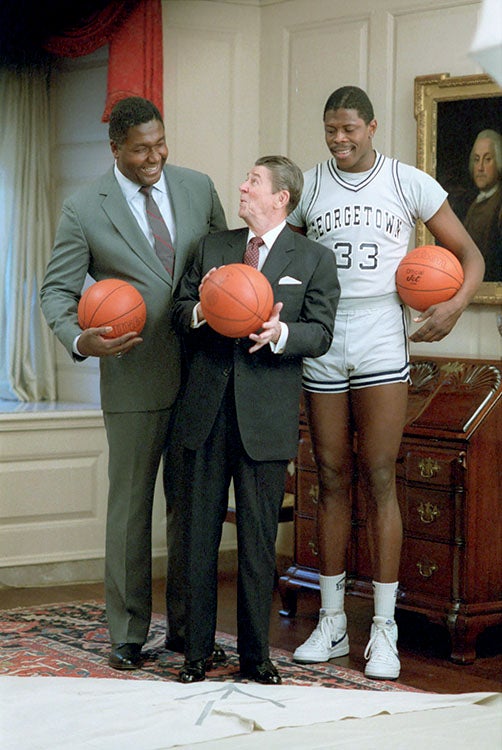

The company he kept was also a source of interest. A few days after the raids, ABC News broadcast a special two-and-a-half hour, live edition of Nightline from Our Lady of Perpetual Help church in Anacostia. Among the revelations that came out of the program was that Edmond – a big basketball fan – had been associating with Georgetown University basketball players, including star center Alonzo Mourning and that coach John Thompson had requested a meeting with the reputed dealer.

As Thompson told host Ted Koppel, “I didn't get into his background or conduct an interrogation; that's for the police. But the legal process is a long one, while the problem is an immediate one. I tried to make sure he knew the goals and objectives of my kids, and [tried to] make it very clear to him that I didn't want anything going on with my kids. I was trying to deal immediately with a specific problem.”[3]

On September 11, 1989, Edmond went on trial along with 10 associates including several family members and Tony Lewis. Edmond was charged with leading a continuing criminal enterprise, which carried a sentence of life in prison.

Authorities implemented unprecedented security measures for the case. The courtroom was equipped with a bulletproof shield separating those involved from spectators. Additional bulletproof panels protected the judge and jurors, and the courtroom was ringed with U.S. Marshals.

In addition, U.S. District Judge Charles R. Richey ordered that the jury be sequestered during the trial and their names be kept secret – even from him – on the grounds that jurors' fear of retaliation by Edmond's network could remove “any semblance of an impartial jury.”[4]

Rather than being detained at D.C. Jail, Edmond was held at Quantico Marine Corps base and flown in daily by helicopter. It was media spectacle.

The trial lasted 56 days. Prosecutors presented Edmond as a charismatic drug mastermind who had learned the trade from his parents at a young age. Jurors heard vivid descriptions of Edmond’s flashy lifestyle, which the prosecution claimed was funded by drugs and violence. The most damaging piece of evidence was a secretly-recorded conversation in which Edmond’s mother, Constance “Bootsie” Perry, told an associate that her son had started off as a small-time drug dealer but then “just got too big” and went out on his own.

Defense lawyers portrayed Edmond as a compulsive gambler who earned up to $50,000 per week playing dice and numbers and used his winnings to fund his lifestyle.

On December 6, the jury reached its decision. Rayful Edmond III was found guilty on all counts and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

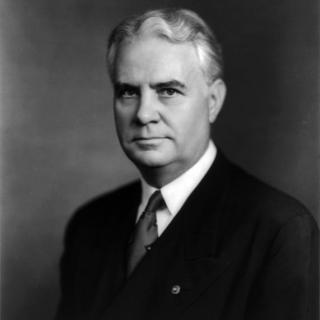

U.S. Attorney Jay Stephens celebrated the verdict and said the case was evidence that law enforcement officials “stand shoulder to shoulder with the people of this community to turn the tide of drugs that have so devastated this city.”[5]

Edmond maintained his innocence, claiming authorities were looking for someone to blame for the drug problems on the D.C. Streets. “I am not the person the U.S. Government is trying to make me out to be.” He also said he believed he would have received a fairer trial if the jury had been racially integrated. (All 12 jurors were black.) “I'm not racist, but white people would have taken their time. They would have gone by the law... This jury never asked any questions about the law. Even me—I'm intelligent—and I studied the legal issues. I didn't understand some of it. I'm not saying they weren't intelligent. They just weren't fair.... They came in too quick.”[6]

It was the longest and costliest drug trial in D.C. history. (Over $258,000 alone had been spent on transporting, housing, feeding and protecting jurors.) Edmond, 24, was sent to the Federal Penitentiary in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania to serve his sentence. And so ended the career of the biggest drug dealer in D.C. history…

Except that it didn’t.

In Lewisburg, Edmond made contacts with other inmates who had connections to Colombia’s Medellin drug cartel (a different cartel from the one with which he had previously dealt) and was soon back in business. Using prison phones, mail and visiting hours, he brokered deals between the Colombian suppliers and D.C. drug dealers. (Edmond would make collect calls from the prison to associates in D.C., who would then patch him through to contacts in Colombia.) He even mediated disputes and persuaded the Colombians not to kill Washington dealers who fell behind in their payments.[7]

For his role, Edmond was paid handsomely, earning over $200,000 before the scheme was discovered. But what good would $200,000 do a man who was locked up for life? For Edmond, his second career represented something more basic. As he explained later, "At the time, my mindset was I had to still have people look up to me and prove that I was still capable of making things happen.”[8]

When word of Edmond’s new enterprise went public in 1996, U.S. Attorney Eric Holder blasted the Federal Bureau of Prisons, “It is intolerable that criminals who were incarcerated for the precise purpose of protecting our citizens have instead been able to use prison facilities as their home offices for creating and commanding massive narcotics enterprises that have left nothing in their wake but death and destruction.”[9]

By then, however, the saga of Rayful Edmond III had taken another twist. In exchange for the government reducing his mother’s sentence – in 1990, Constance Perry had received a 14 year sentence for her participation in her son’s drug ring – Edmond reached a deal to become a government informant. Operating from inside the prison system, he began setting up drug traffickers on the outside for law enforcement to take down.

In 1998, Edmond’s testimony helped convict 11 people on drug trafficking charges. His mother was released from prison and he was put into the prison system’s witness protection program. His current location of incarceration is confidential.

Update: In February 2021, U.S. District Judge Emmet G. Sullivan cited Edmond’s cooperation with prosecutors in other drug and homicide cases, and reduced Edmond’s prison sentence for his D.C. case from life without parole to 20 years. However, he still remains incarcerated due to a pending 30-year prison sentence for orchestrating drug deals from the Federal Penitentiary in Lewsiburg, Pennsylvania.

Footnotes

- ^ Horwitz, Sari, “Sweep Broke Drug Ring, Officials Say,” The Washington Post, 18 Apr 1989: A1.

- ^ Walsh, Elsa, “Edmond Convicted on All Counts in Drug Conspiracy Case,” The Washington Post, 7 Dec 1989: A1.

- ^ Wilbon, Michael, “Thompson Met with Drug Suspect to 'Confront Problem,'" The Washington Post, 29 Apr 1989: D1.

- ^ Lewis, Nancy, “Edmond Trial to Begin with D.C.'s First Use of Anonymous Jury,” The Washington Post, 10 Sep 1989: B1.

- ^ Walsh, Elsa, “Edmond Convicted on All Counts in Drug Conspiracy Case,” The Washington Post, 7 Dec 1989: A1.

- ^ Walsh, Elsa, “Edmond: I felt Railroaded,” The Washington Post, 12 Dec 1989: A1.

- ^ Locy, Toni, “Notorious D.C. Drug Dealer Turns Informer to Aid Mom,” The Washington Post, 9 Aug 1996: A1.

- ^ Locy, Toni, “Convicted Drug Kingpin Reveals Empires Riches,” The Washington Post, 25 Feb 1997: B1.

- ^ Locy, Toni, “Notorious D.C. Drug Dealer Turns Informer to Aid Mom,” The Washington Post, 9 Aug 1996: A1.

Other Sources

Horwitz, Sari, “Sweep Broke Drug Ring, Officials Say,” The Washington Post, 18 Apr 1989: A1.

Lewis, Nancy and Sari Horwitz, “16 Linked to Drug Gang Arrested in Area Sweep,” The Washington Post , 17 Apr 1989: A1.

Lewis, Nancy and Sari Horwitz, “Area Sweep Nabs Alleged Drug Leaders,” The Washington Post, 16 Apr 1989: A1.

Lewis, Nancy, “Edmond's Mother Among 9 Guilty on Drug Charges,” The Washington Post, 31 Mar 1990: A1.

Lewis, Nancy, “Edmond Trial to Begin with D.C.'s First Use of Anonymous Jury,” The Washington Post, 10 Sep 1989: B1.

Locy, Toni, “For Jailed Kingpins, A Cocaine Kinship,” The Washington Post, 19 Aug 1996: A1.

Locy, Toni, “Notorious D.C. Drug Dealer Turns Informer to Aid Mom,” The Washington Post, 9 Aug 1996: A1.

Locy, Toni, “Convicted Drug Kingpin Reveals Empires Riches,” The Washington Post, 25 Feb 1997: B1.

Shinn, Anniys, “Running Low on Rayful,” Washington City Paper, 8 Sep 2000.

Thompson, Tracy, “As Anonymous as the Trial Was Long,” The Washington Post, 7 Dec 1989: A23.

Walsh, Elsa, “Addicted to the Dollar,” The Washington Post, 23 Apr 1989: A1.

Walsh, Elsa, “Edmond Convicted on All Counts in Drug Conspiracy Case,” The Washington Post, 7 Dec 1989: A1.

Walsh, Elsa, “Edmond: I felt Railroaded,” The Washington Post, 12 Dec 1989: A1.

Wilbon, Michael, “Mourning in Court: A Lesson on Friends and Foes,” The Washington Post, 23 Nov 1989: B3.

Wilbon, Michael, “Thompson Met with Drug Suspect to 'Confront Problem,'" The Washington Post, 29 Apr 1989: D1.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)