Impressions of Washington: Charles William Janson, 1807

Throughout the history of the capital, people have thought of it as… a pretty bad place, honestly. From Lead Belly in 1937, to Mark Twain and Charles Dudley in 1873, to Nathaniel Hawthorn in 1862, to Byron Sunderland in the 1850s, to Charles Dickens in 1842, to a British Chaplin in the War of 1812, to Abigail Adams in 1800, it seems like pretty much everyone has disliked the District. If you don’t want to read one more, skip to the bottom to check out the people who, somehow, against all odds, actually like the city — if not, read on!

Charles William Janson was an Englishman who lived in and wrote about America from 1793 to 1806. He published the account of his travels in 1807, in The Stranger in America. The following is what he had to say about what was then called “Washington City.”

The entrance, or avenues, as they are pompously called, which lead to the American seat of government, are the worst roads I passed in the country; and I appeal to every citizen who had been unlucky enough to travel the stages north and south leading to the city, for the truth of the assertion. In the winter season, during the sitting of Congress, every turn of your wagon wheel is for many miles attended with danger. The roads are never repaired; deep ruts, rocks, and stumps of trees, every minute impeded your progress, and often threaten your limbs with dislocation.

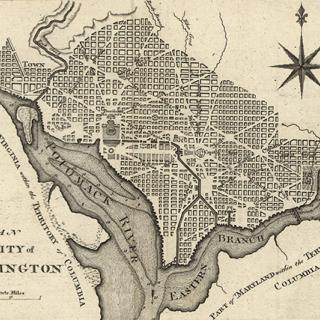

Arrived at the city, you are struck with its grotesque appearance. In one view from the Capitol Hill, the eye fixes upon a row of uniform houses, ten or twelves in number, while it faintly discovers the adjacent tenements to be miserable wooden structures, consisting, when you approach them, of two or three rooms one above another.

The country adjoining consists of woods in a state of nature, and in some places of mere swamps, which give the scene a curious patchwork appearance. The view of the noble river Potomack, which the eye can trace til it terminates at Alexandria, is very fine. ????

The president’s house is situated one mile from the Capitol, at the extremity of Pennsylvania Avenue. The contemplated streets of this embryo city are called avenues, and every state gives name to one. The Pennsylvania is the largest; in face I never hear of more than that and the New Jersey Avenue… this boasted avenue is as much a wilderness as Kentucky, with this disadvantage, that the soil is good for nothing. Some half-starved cattle browsing among the buses, present a melancholy spectacle to a stranger. So very thinly is the city peopled, and so little is it frequented, that quails and other birds are constantly shot within a hundred yards of the Capitol, and even during the sitting of the houses of Congress.

The president’s house is certainly a neat but plain piece of architecture, built of hewn stone, said to be of better quality than Portland stone, as it will cut like marble, and resist the change of seasons in a superior degree. Only part of it is furnished; the whole salary of the president would be inadequate to the expense of completing it in a style of suitable elegance.

The ground around it, instead of being laid out in a suitable style, remains in its ancient rude state, so that, in a dark night, instead of finding your way to the house, you may, perchance, fall into a pit, or stumble over a heap of rubbish. The fence around the house is of the meanest sort; a common post and rail enclosure. This parsimony destroys every sentiment of pleasure that arises in the mind, in viewing the residence of the president of a nation, and is a disgrace to the country.

Well! And now, as promised, some more positive reviews to cool off with: Friedrich Ratzel in 1874, William Howard Russel in 1861, Maximilian Hartman in 1861, 1850s Georgetown 4th of July, and Frances Few in 1808.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)