The First Leading Lady of Washington: Marcia Van Ness

In the historic society of Washington, there has always been a woman at the top. Sometimes she rules with an iron fist, sometimes it’s with charm, but she does rule. And the very first of these ladies was Marcia Van Ness.

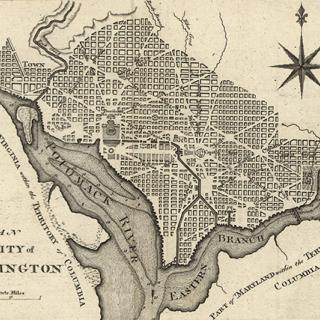

This future “heiress of Washington” got her start as Marcia Burnes, the daughter of David Burnes, a stubborn Scottish farmer. In 1790, the new location for the capital was chosen, George Washington got to know Mr. Burnes very well. Possibly too well, in the president’s opinion. Although every other farmer in the new District had accepted the change and gave up their land to development, David Burnes refused to turn over his tobacco fields. It took a personal visit from Washington and more than a little cajoling to change the Scotsman's mind.

When he did change his mind, Burnes became an instant millionaire. He owned 600 acres in the middle of the new Washington City, and people were eager to buy. After the death of her older brother, Marcia stood to inherit her father’s entire fortune. In the burgeoning society, she was more than a catch. And she had charms beyond her father’s money. One later newspaper referred to her as “the fairest belle in all the realm.”[1] She had attended a respected finishing school in Baltimore and could dance the minuet and gavotte, finely embroider, and was well-versed in French and literature.

As her father’s cottage was the only building for miles around, Marcia met every eligible man in government. She eventually chose the young and handsome John Peter Van Ness, a congressman from New York, who was reportedly “well-fed, well-bred, and well-read.”[2] It was an excellent match, as in his lifetime John would go on to be a general, the mayor of Washington, the president of two banks, and a commissioner supervising the reconstruction of the destroyed city.

The couple at first stayed in the Burnes cottage after their marriage, and then in a brick house just off Pennsylvania Ave on 12th street, but this was all in wait of the extravagant Van Ness Mansion. Said at the time to be the “finest house in America,” no expense was spared; the final product cost over $75,000.[3] They hired Benjamin Latrobe, the architect for the Capitol building, to get the job done and boy, did he deliver. Besides the marble mantels carved in Italy, gorgeous white portico, and extensive wine vaults, the house was also at the forefront in comfort: both hot and cold running water was available on every level of the house.

The parties thrown in the Van Ness Mansion were famous, attended by all the very best in Washington, such as the Madisons, the Monroes, the Decaturs, and the Tayloes. Marcia remained in the cream of society, known to all who were distinguished. Washington Irving, author of “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” was a guest in their home and described her as “a pretty and pleasant little woman, and quite gay.”

Marcia Van Ness was not just the toast of the upper crust, she was also a heroine to the city’s needy children. The War of 1812 left many young residents without parents. and the newly created “Washington City Orphan Asylum” dedicated itself to the cause. Marcia was fundamental in creating the asylum, but she promoted First Lady Dolley Madison as board director, to bring prestige to their efforts. Orphans, possibly only girls, were taken in and spent their days learning to read and write and being trained in domestic work to support themselves as adults. The asylum was first housed on Van Ness land but went through many locations and changes over the years. It exists today as the Hillcrest Children and Family Center.

The benefactress’s life was not without her own sorrow, however. Marcia’s daughter and newborn grandchild both went to the grave in 1823, taken by a summer illness infecting the swampy capital. After 1823, Marcia exited society and instead threw herself into her charity. When the Burnes fortune, over $1.5 million, finally passed to her, she turned it over to her husband and continued to devote herself to the orphans of Washington. When Mrs. Madison left the capital in 1817, First Lady Elizabeth Monroe declined the position of director and Marcia took the helm.

She remained director of the Washington City Orphan Asylum until her death at age 50, on September 10, 1832. Congress was in full session but adjourned on the day of her funeral to honor her passing, an exceedingly high honor, and extremely rare for a woman. Washington citizens voted to attach a silver plate to her coffin. Sources differ on exactly what was written, but it may have gone something like:

The citizens of Washington in testimony of their veneration for departed worth dedicate this plat to the memory of Marcia Van Ness, the excellent consort of John Peter Van Ness. If piety, charity, high principle and exalted worth could have averted the shafts of fate, she would have still remained among us, a brighter example of every virtue. The hand of death has removed her to a purer and happier state of existence, and while we lament her loss, let us endeavor to emulate her virtues.

Whatever the plate said, her funeral was well attended and orphans dressed in the green uniform of the asylum sung a prayer and laid willow branches on her coffin. She was buried in the Van Ness Mausoleum, which today stands in Oak Hill Cemetery.

Marcia Van Ness was born the daughter of a humble planter in an undistinguished wilderness, but she died honored by Congress in the nation’s capital. Although not widely remembered today, her story reflects the transformation of Washington in its earliest days.

Footnotes

- ^ Lockwood, Mary S. “Historic Homes of Washington: Noted Men and Women who have Inhabited Them.” The National Tribune. (Washington, D.C.), 25 Nov. 1897. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ “Historic Houses of Washington.” Washington, D.C.: A Turn of the Century Treasury. Ed. Frank Oppel and Toney Meisel. (Castle: 1987).

- ^ Huntington, Frances Carpenter. “The Heiress of Washington City: Marcia Burnes Van Ness, 1782-1832.” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C., Vol. 69/70 (1969/70).

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)