The Silent Sentinels Pushed Washington for Women's Suffrage

On January 9, 1917, a delegation of 300 prominent women from across the country visited the White House and presented President Woodrow Wilson with a written appeal for voting rights.

“We desire to make known to you, Mr. President, our deep sense of the wrong being inflicted upon women, in making them spend their best health and strength, and forcing them to abandon other work that means fuller self expression, in order to win freedom under a government that professes to believe in democracy. No price is too high to pay for liberty. So long as the lives of women are required, these lives will be given.”[1]

They would leave disappointed. As he had done many times over the previous four years, Wilson reiterated his stance that women’s suffrage was a matter to be decided by the states rather than by federal mandate. He would not push the issue.

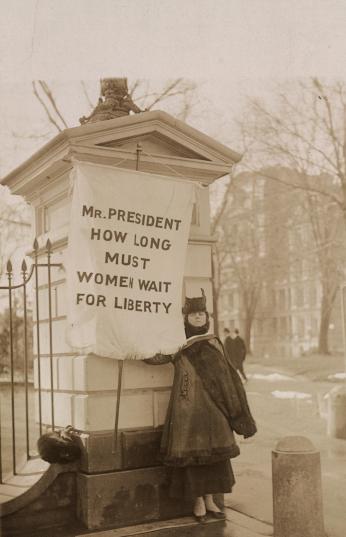

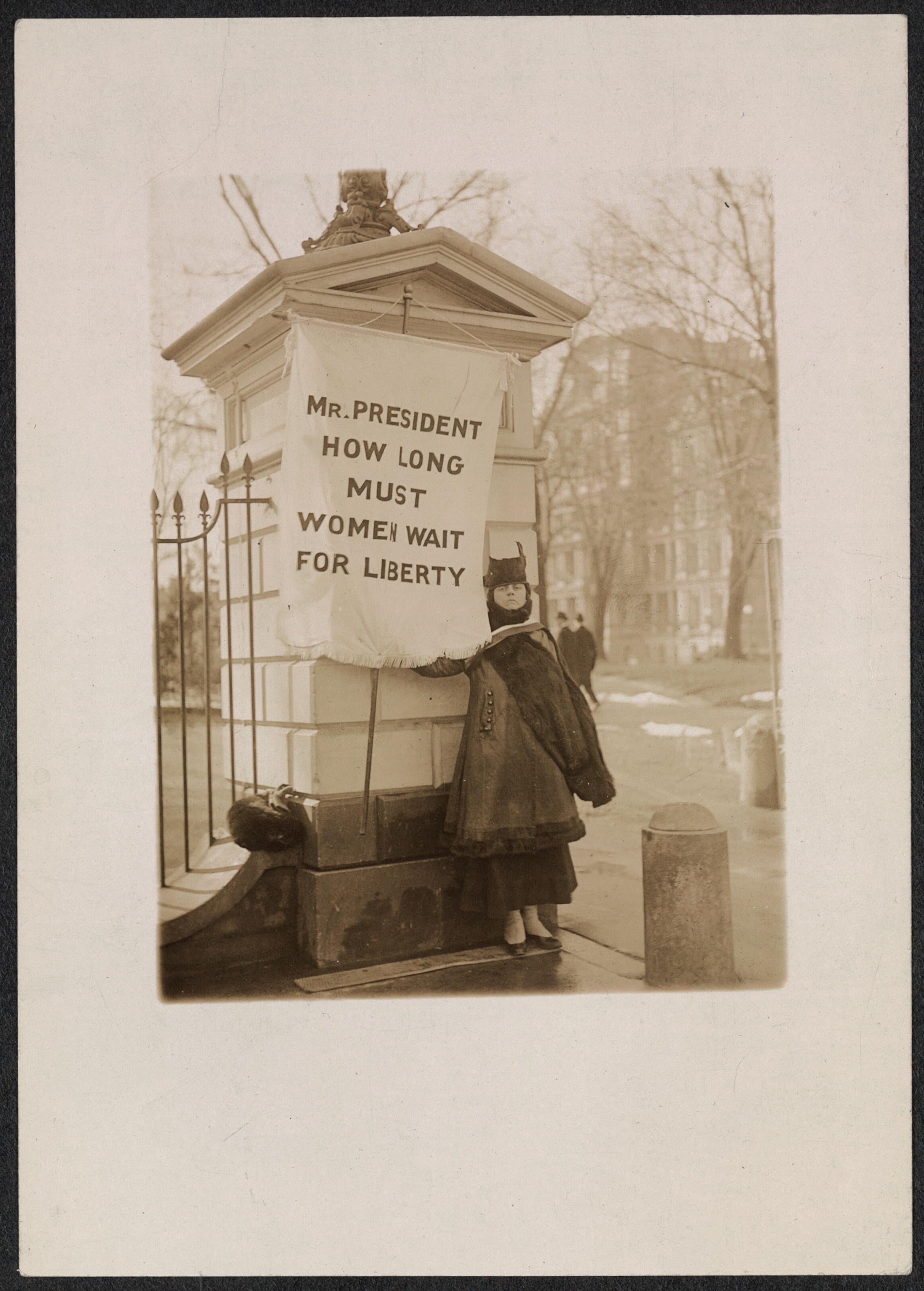

At 10 o’clock the next morning, 12 women from the National Woman’s Party took up posts outside the White House entrances.[2] They stood in silence, wearing purple, yellow, and white ribbons, and holding large banners, which read:

“Mr. President, what will you do for woman suffrage?”

The idea behind the vigil, which organizers planned to continue on a daily basis, was to make it impossible for the President to enter or exit the executive mansion without being confronted with the suffrage question. Though tame by today’s standards, The Washington Herald called the effort “the most militant move ever made by the suffragists of this country.”[3]

The protests attracted state delegations from across the country. Organizers also promoted special days to attract particular groups – teachers day, lawyers day, artists and musicians day, wage earners day, and others – which they called “chapters of a serial story on the nationwide demand of women for the passage of the federal suffrage amendment.”[4]

Beyond waving as he passed through the White House gate, Wilson seemed unmoved by the protests at first. According to Metropolitan Police, he gave orders that the suffragists should not be removed as long as the demonstrations remained peaceful.[5] Meanwhile, the reaction the so-called “Silent Sentinels” garnered from everyday Washingtonians was mixed. Some expressed their support for the women’s efforts; others heckled.

Criticism picked up after the country entered World War I on April 6. As one reader wrote to The Washington Post:

“It seems to be that the President, especially in these trying days, should be spared every annoyance that can be possibly averted, and surely the cause of woman suffrage is not helped by resorting to these bad manners and mad banners.”[6]

A few days later, The Evening Star suggested that the demonstrators should redirect their efforts to more patriotic pursuits, “Suffragists who do picket duty outside the White House gates could do the country more good if each went out and obtained five men for the navy.”[7]

For their part, the demonstrators balked at the idea that their efforts were unpatriotic. As a spokeswoman for the picketers told the press, “The necessity for protest against discrimination was never greater than it is today, when such important decisions are being made…. American women are as ready as men to serve their country by every means in their command. When they ask for a share in the government women are only seeking a more complete opportunity for patriotic service.”[8]

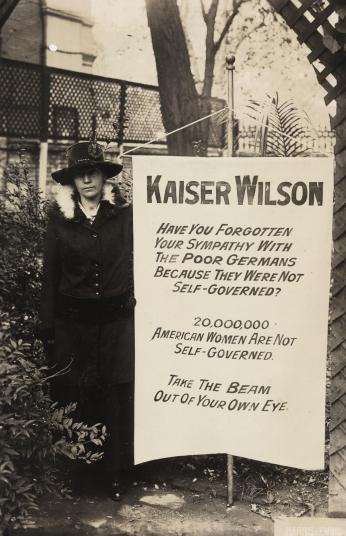

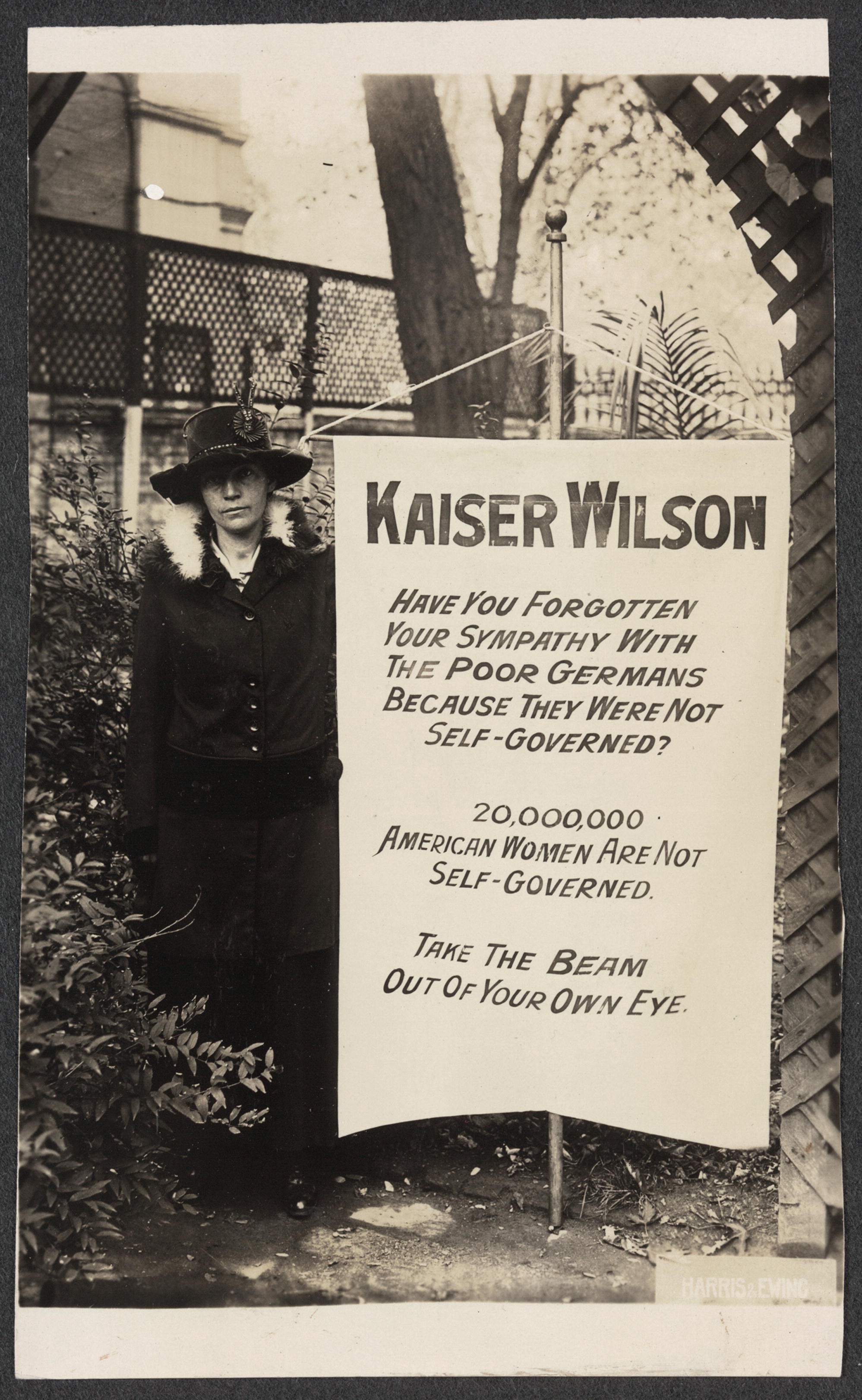

In late June, tensions grew when the demonstrators unfurled a 10-foot banner addressed to a Russian delegation, which was in Washington to meet with Wilson at the White House. It read, “To the Russian mission: President Wilson and Envoy Root are deceiving Russia. They say ‘we are a democracy.’ Help us win a world war so that democracies may survive. We, the women of America tell you that America is not a democracy. 20,000,000 American women are denied the right to vote. President Wilson is the chief opponent of their national enfranchisement. Help us make this nation really free. Tell our government that it must liberate its own people before it can claim Russian as an ally.”[9]

A mob of incensed men and women tore the banner down, accusing the demonstrators of sedition and treason. When a similar scene broke out the next day, police changed their stance. The demonstrators and the crowds that gathered to oppose them were told to move or risk arrest for “obstruction of traffic.” When two picketers—Lucy Burns and Katherine Morey—refused to do so on June 22, they were arrested. Many more arrests would follow as authorities grew increasingly impatient with the protests and associated clashes.

The protests reached a boil in mid August when, on several occasions, picketers displayed banners addressing the president as “Kaiser Wilson.” Mobs of counter protesters rushed them and destroyed the banners. Police did little to intervene before arresting several picketers.

As a strategic maneuver to call attention to their cause, arrested picketers routinely declined to pay fines in favor of serving sentences at the Occoquan Workhouse, the reformatory that the District government had opened in Fairfax County a few years earlier. Initially, sentences were short – three days – but they grew to six months as the protests continued.

Soon disturbing reports started coming out of the Workhouse. Virginia Bovee, who was fired from her position as a night officer, alleged that Superintendent William Whittaker and his son beat the jailed picketers. Bovee also described disgusting living conditions at the workhouse, where bedding was rarely changed and worms were routinely found in food supplies.[10]

The District government pledged to investigate the situation. Perhaps not surprisingly, its review offered a very different appraisal. “We can and do conscientiously state that we found absolutely nothing to criticize in this institution on in any of its parts. Occoquan appears to us, with its wide, open spaces and lack of bars, more like a country summer resort than a penal institution, and as far as health is concerned we believe that it would be difficult to find more comfortable and hygienic surroundings.”[11]

On Oct. 4, guards and picketers clashed inside the prison when the suffragists tried to prevent officers from removing Mrs. Margaret Johns who they said had been ill. While the guards claimed she would be taken to a hospital, Johns refused to go and other prisoners became worried that she would be placed in solitary confinement.

The unrest continued as picketers refused to carry out their assigned work tasks (sewing, gardening, etc.) and went on a hunger strike in attempt to be recognized as political prisoners, rather than common criminals. After several days, guards resorted to force feedings. As Burns detailed in her secret jailhouse diary, it was a horrific experience.

“I was held down by five people at legs, arms, and head. I refused to open mouth. Gannon pushed tube up left nostril. I turned and twisted my head all I could, but he managed to push it up. It hurts nose and throat very much and makes nose bleed freely.”[12]

According to Burns and affidavits from several other women, the night of Nov. 14 brought on a new level of abuse. At the instruction of Superintendent Whittaker, guards violently rounded up the picketers and forced them into cells on the men’s side of the workhouse. They were threatened throughout the night while Burns was handcuffed to the jail bars and left wearing only a blanket.

The incident, which picketers called the “Night of Terror,” seemed to be a clear attempt to break their resolve and some, such as Eunice Dana Brannan, suspected the order came from outside the prison.

“The guards… acted brutal in the extreme, incited to their brutal conduct towards us, … by the superintendent. I thought of the offense with which we had been charged—merely that of obstructing traffic—and felt that the treatment that we had received was out of all proportion with the offense that we were charged, and that the superintendent, the matron and guards would not have dared to act towards us as they had acted unless the relied on support of higher authorities.”[13]

Two weeks after the “Night of Terror,” the prisoners were released and news of their ordeal started to trickle out to newspapers. Many Americans were appalled including, apparently, Wilson. On January 9, 1918 – almost a year to the day after the Silent Sentinels began their “militant” protest – Wilson announced his support for a federal amendment for women’s suffrage. Two months later, the arrests, trials and punishments of the picketers were ruled unconstitutional by the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Was Wilson's change of heart a direct result of the pickets? It’s difficult to say, but it’s clear that the sentinels helped keep the suffrage issue in the American consciousness as the nation's involvement in the war acclerated. Ultimate victory finally came in August 1920 when the 19th Amendment granting all American women the right to vote was ratified.

Footnotes

- ^ “Suffragists Pickets to Patrol White Lot,” The Washington Herald, January 10, 1917, 3. Accessed March 17, 2016 via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress.

- ^ The National Woman’s Party, led by Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, grew out of the older Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage.

- ^ "Pickets Posted at White House Today by Women," The Washington Herald, January 10, 1917. The strategy of picketing the White House was not universally embraced by suffrage groups beyond the National Woman’s Party. Many for suffrage advocates (such as the National American Woman Suffrage Association) worried that the public displays would actually turn voters off and hurt their cause. Some state groups even blamed the NWP’s White House picketing on failed state votes on suffrage.

- ^ “Seventeen Special Days Planned,” The Evening Star, January 24, 1917, 13.

- ^ “Obnoxious Banner Is Torn to Shreds,” The Evening Star, June 20, 1917, 1.

- ^ “‘Bad Manners, Mad Banners’ of the White House Pickets,” The Washington Post, April 23, 1917, 8.

- ^ “Suggestion to the Pickets,” The Evening Star, April 25, 1917, 2.

- ^ “Suffragist Pickets Stay at White House,” The Evening Star, February 3, 1917, 13.

- ^ “Obnoxious Banner Is Torn to Shreds,” The Evening Star, June 20, 1917, 1.

- ^ “Ex-Officer Files Charges Against Occoquan Heads,” The Washington Times, August 29, 1917, 3. Accessed March 17, 2016 via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress.

- ^ “Pickets ‘Jovial’ and Not Unhappy,” The Evening Star, November 23, 1917, 11.

- ^ Doris Stevens, Jailed For Freedom (New York: Boni & Liveright, Inc.), 1920: 201.

- ^ Doris Stevens, Jailed For Freedom (New York: Boni & Liveright, Inc.), 1920: 205.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)