The Little Italy Under the Parkway

Few would believe that Arlington County once contained its own Little Italy – and few would recognize it if they saw it. Unlike the prototypical image of urban markets and crowded apartments, what Arlingtonians once referred to as "Little Italy" (or "Little Sicily") was an isolated makeshift village occupied by Italian quarrymen and their families on the banks of the Potomac, accessible only by footpath.

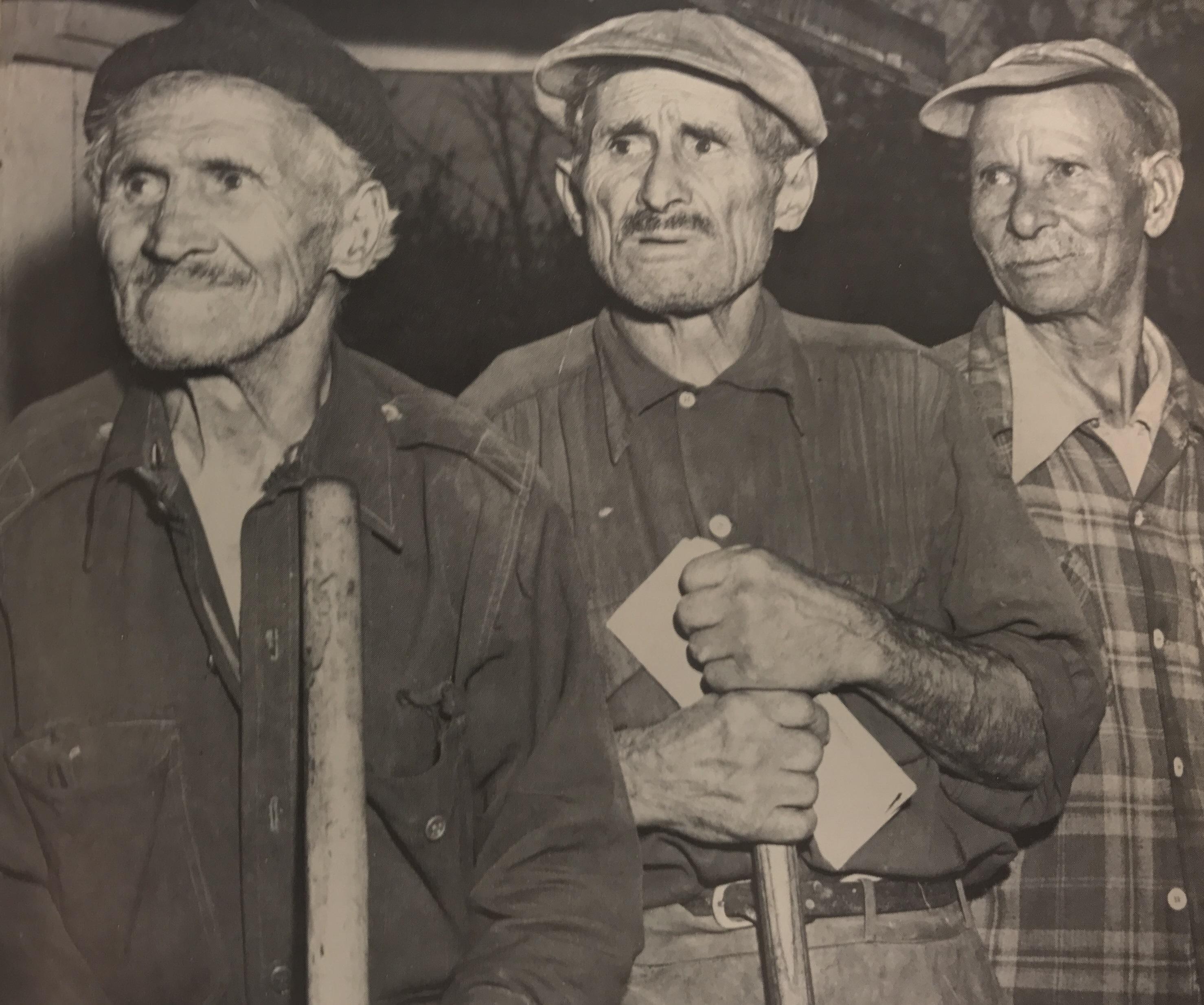

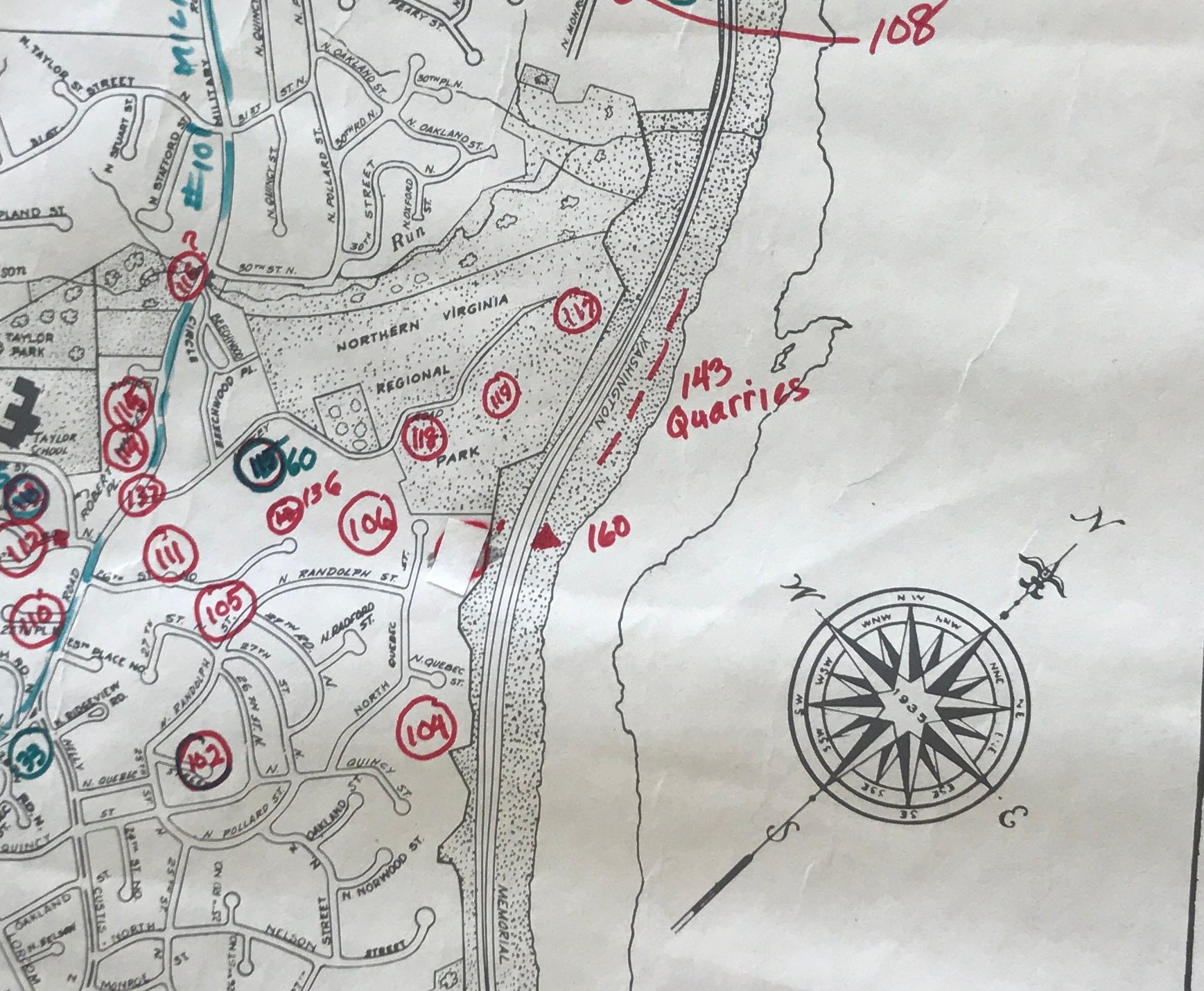

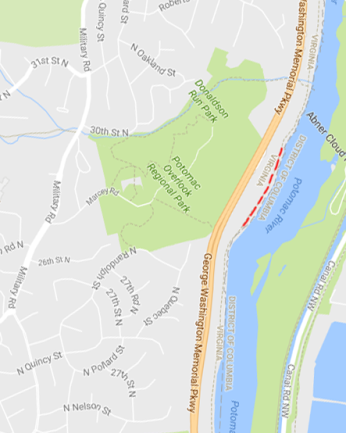

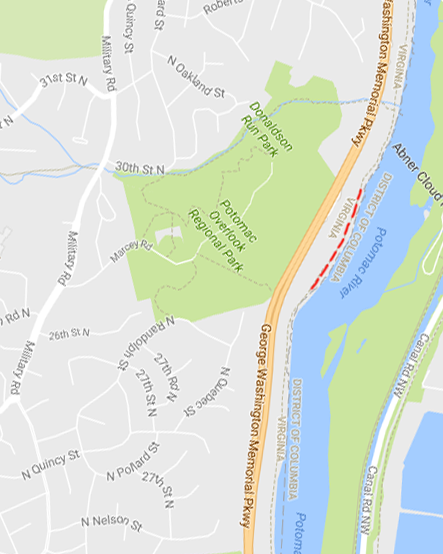

This obscure and bizarre part of Arlington's history is, unsurprisingly, quite poorly documented. Most information about the settlement and perhaps the only known photographs of its residents come from a 1956 Evening Star article and a few pages in Eleanor Lee Templeman's book Arlington Heritage, published three years later. Though listed by Templeman as a "destroyed site"[1] in a 1973 letter to the Arlington Historical Society, remnants of the Little Italy quarry can still be found today. Along the Potomac Heritage trail near Potomac Overlook Regional Park, stranded, rusting quarry equipment remains an unexplained and often confusing sight for hikers.

First acquired as farmland by New York entrepreneur Gilbert Vanderwerken in 1851, the quarry site switched hands several times between various quarrying companies (and for a brief period, the Union Army)[2] for the next 80 years. The quarry produced a "fine granite bluestone"[3] that was hauled to Washington on barges and used in the construction of notable D.C sites, including St. Patrick’s Church and the Healy building at Georgetown University. Also extracted was rubble, much of which was used to lay the foundation of the city's roads.[4]

While the Italians were not the only men working in the north Arlington quarry (roughly 100 African American quarrymen from Westmoreland County were employed seasonally alongside them), the Italians were the only ones to form a self-sufficient ethnic enclave on the quarry site itself. In its heyday (approximately 1910-1938), Little Italy was home to roughly 30 workers and their families who lived in self-made “shacks,” a word used with pride by one of the community’s last residents.[5] Despite its unusual location and circumstances, the enclave developed many of the trappings of a normal neighborhood, including its own general store, and even an unofficial mayor – Michele Dimeglio.[6] As a result, Little Italy was able to function almost in isolation from Arlington County, likely exacerbated by the fact that much of its population spoke only Italian.[7]

Most of Little Italy’s residents entered the United States at the turn of the century by way of southern Italy, hailing usually from Naples or the island of Sicily. Today their pay seems meager, though it was relatively decent alongside the wages of comparable sites. Dynamiter Philip Natoli was initially drawn to the quarry in 1906 for its $1.50 a day wage, an amount translating to roughly $39 today.[8] Explaining in 1956 his decision to come to Washington, he said:

“Fifty-two years ago I leave Messina (Sicily)…land New York, New Jersey. I dig ditches … ¢80 a day. 10 hours work every day. In two years, I hear about stone quarry Washington. Pays $1.50 a day, so I come.”[9]

What is known of daily life in the settlement comes from the recollections of its last three residents – Philip Natoli (quoted above) and the Conduci brothers Josh and Carl (formerly Guiseppe and Carmelo). The picture they paint is predictably gritty, colored mostly by the dangers of quarrying in the early 20th century. Though few records of injuries exist, Natoli recalled a dramatic rockslide which left his heel shattered and his brother without a leg.[10] Newspaper articles during the quarry's operation often talk of tugboat accidents, though the Conduci brothers (who worked as barge loaders) never mentioned whether they were involved. Despite the occasional accident, the quarry workers were skilled and precise. Remembering his experiences observing the quarry as a boy, Charles Grunwell (Gilbert Vanderweken’s grandson) described the workers with awe:

“The seemingly careless and indifferent way the two men brought their hammers from behind their shoulders and crashed them down on the drill bar fascinated me. At every stroke, I feared the hammer would miss, but during the times I watched it never did.”[11]

The dangers of Little Italy were not confined to the job. Due to its relative isolation, the community had few ties to law enforcement or the fire department. This left Little Italy vulnerable to both fire and crime, including a fire that destroyed "mayor" Dimeglio's residence, as well as a shooting that left Carl Conduci permanently disabled. The perpetrator, "habitual trouble-maker" Mike Sunday, was never reported to the police, though he supposedly "met a violent death" in New York City.[12]

The exact origin of Little Italy's decline and current obscurity is unclear. Sometime between 1938 and 1941, the quarry’s final owner, Smoot Sand & Gravel, ceased operation of the site. Perhaps, this was in relation to a 1939 strike in which Smoot employees (though likely no quarrymen) picketed for mandatory union membership. Lasting from August to September, the strike affected $54,000 worth of construction projects, leading one journalist to claim it brought losses so great that "no one will attempt to estimate the cost."[13] Regardless of the exact reason for the quarry's closure, the lack of work in Little Italy decimated its population. Over the following decade, Little Italy's 30 households shrunk only to the two shacks of Philip Natoli and the Conduci brothers, who continued to pay a 10 cents per month rent to Smoot Sand & Gravel until collections stopped in 1948.[14]

It is this period following the end of quarry operations that is perhaps most compelling. Without the quarry to support themselves, Little Italy's final residents survived in two ways. While they received some income from what they referred to as their "pensh" (Social Security), most of their needs were provided by the land they lived on. Along the banks of the Potomac, Natoli and the Conducis tilled the land, subsiding off their own vegetable gardens and fish taken from the river. Occasionally, they would sell flowers grown on their land, though many remained to decorate their shacks.[15] Imagining such a sight on the Potomac Heritage Trail today is an odd though heartwarming exercise.

Their quiet, subsistence-style existence however met an abrupt and unexpected end. After lengthy deliberations with Smoot Sand & Gravel (which initially asked for double what their land was worth), the National Capital Parks and Planning Commission acquired the land where the quarry once operated in order to construct the Spout Run extension to the George Washington Memorial Parkway.[16]

On December 6, 1956 the Conducis received a letter informing them of their eviction. Whether or not they or Mr. Natoli fully understood the letter’s content is unsure – their English was poor, and census records three decades prior had listed them as illiterate.[17] The Park Service allowed them roughly a month to vacate their land, pledging them “full cooperation.” “Full cooperation,” however, was limited to two options: either the Conducis and Natoli could dismantle their shacks themselves, or they could let the Park Service demolish them on their own. The letter concludes:

“It is regretted that we have been unable to work out any solution of the problem that might relieve some of the hardship involved, but since no solution can be ascertained that would be in the Federal interest, your cooperation in vacating the premises without delay will be greatly appreciated”.[18]

The three never responded to the notice. Instead, they only watched as bulldozers slowly encroached on the homes they had lived in for half a century. On January 22, seven days after they were supposed to have left, they received a final notice informing them that they were in “unlawful possession”[19] of the land. They soon evacuated, uprooting many of their flowers to donate to the Quebec street home of Mrs. Shippens, a former employer who provided them with occasional landscaping work. Already approaching their early 80's, the three veterans of Little Italy, aided by the son of Michele Dimeglio, spent their last years on a Prince William County farm.[20]

One history of the Parkway comments that the road’s creation put an end to the quarry operations that "disfigured" the natural beauty of the Virginia Potomac.[21] Undeniably, the Parkway did much to preserve the area. Lost though was Arlington’s Little Italy, forever buried underneath.

Footnotes

- ^ Templeman, Elearnor Lee, Eleanor Lee Templeman to the Arlington Historical Society. Letter. Sep. 1, 1973. George Mason University Special Collections, Eleanor Lee Templeman Collection.

- ^ Templeman, Eleanor Lee, Arlington County Heritage. (1959) 128

- ^ Templeman, Eleanor Lee, Arlington County Heritage. (1959) 142

- ^ Grunwell, Charles. "Bluestone from the Hills". The Evening Star 30 Jan. 1966. 110

- ^ Beverdige, George. "Three Aged, Bewildered 'Shack' Survivors Watch Bulldozers Remove 'Little Sicily'. The Evening Star. 4 Nov. 1956. 38

- ^ Templeman, Eleanor Lee, Arlington County Heritage. (1959) 142

- ^ 1920 United States Federal Census; Census Place: Washington, Alexandria, Virginia; Roll: T625_1879; Page: 23B; Enumeration District: 15; Image: 1089

- ^ Beverdige, George. "Three Aged, Bewildered 'Shack' Survivors Watch Bulldozers Remove 'Little Sicily'. The Evening Star. 4 Nov. 1956. 38

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Templeman, Eleanor Lee, Arlington County Heritage. (1959) 142

- ^ Grunwell, Charles. "Bluestone from the Hills". The Evening Star 30 Jan. 1966. 110

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ "A Costly Strike". The Washington Post Sep. 6 1939. 8

- ^ Templeman, Eleanor Lee, Arlington County Heritage. (1959) 142

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Historic American Engineering Record. ”George Washington Memorial Parkway"

- ^ 1920 United States Federal Census; Census Place: Washington, Alexandria, Virginia; Roll: T625_1879; Page: 23B; Enumeration District: 15; Image: 1089

- ^ Thompson, Harry T. Harry Thompson to Josh and Carl Conduci, Dec. 6, 1956. Letter. From the Arlington County Public Library Special Collections.

- ^ Thompson, Harry T. Harry Thompson to Josh and Carl Conduci, Jan. 22, 1957. Letter. From the Arlington County Public Library Special Collections.

- ^ Eleanor, Templeman Lee. Arlington County Heritage. (1959) 142

- ^ Historic American Engineers Record. "George Washington Memorial Parkway"

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)