John Fahey and the D.C. Roots of an American Genre

When it comes to music, Washington D.C is known as the birthplace of Go-Go, and a foundational city for Hardcore Punk. However, the city’s musical presence doesn’t end there. Perhaps less well known is D.C’s importance for American Primitive Guitar, a somewhat more obscure though nevertheless highly influential genre.

For the unfamiliar, American Primitive Guitar is a type of folk music centered around solo, fingerstyle steel-string guitar (occasionally with vocals and accompaniment), drawing diverse inspiration from Blues artists of the 20's, dissonant 20th century classical music, and the Indian raga tradition. Though it coincided with the folk-pop boom of the 1960s, American Primitive Guitar is a distinct tradition that influenced a wide range of artists including Sonic Youth, Joanna Newsom, and The Who amongst others.

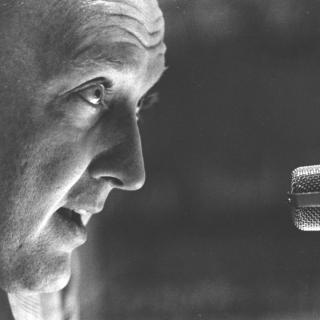

It is relatively rare that one can define a genre’s exact beginning and founder. In the case of American Primitive Guitar, however, this task is easy – it was John Fahey.

Fahey grew up in Takoma Park, Maryland where he spent a largely isolated childhood. His earliest comfort was the woods along Sligo Creek; as he grew older, he found comfort in music. In his early adolescence, Fahey became devoted to Arlington, Virginia’s now defunct bluegrass and country station WARL AM (once among the top American Roots stations in the country).

“You could say that the reason we took the music and the [DJ] personas so seriously --- the reason why we discussed the virtues of this or that record was to feel something good. Rather than despair we felt as a result of the stupid and reckless activities of Mom and Dad. The lack of attention they paid to us. WARL helped us escape the terrible sad we all felt .” [1]

It was on WARL when at the age of 13, Fahey first heard Bill Monroe’s “Blue Yodel no. 7,” an incredibly impactful experience:

“I heard this horrible crazy sound. And I felt this insane mad feeling. Neither of which was I in any manner acquainted. It was the bluesiest and most obnoxious thing I had ever heard. It was an attack of revolutionary terrorism on my nervous system through aesthetics … nothing has ever been the same since.”[2]

This experience, combined with the social currency he believed it might give him, inspired Fahey to purchase his first guitar – a $17 Silvertone from Sears.[3] Teaching himself to play (hence the “primitive” in American Primitive Guitar), he tried to emulate the bluegrass and Country-Western musicians he heard on WARL. Bluegrass, however, would not be the defining influence in Fahey’s music. Another experience several years later hit him even more viscerally than the last.

As teenagers, Fahey and his friend Dick Spottswood (formerly of WAMU) scoured the record stores of D.C and Baltimore in search of old bluegrass recordings. Fahey recalled of the area’s rich opportunities:

"Canvassing in and around Washington and Baltimore, as far north as Havre de Grace and even Philadelphia, I found hundreds of hillbilly and race records. A copy of 'God Moves on the Water', [on] Cherry Avenue, Takoma Park. Stump Johnson on Paramount doing 'I'll Be Glad When You're Dead You Rascal You' and 'West End Blues' by Louis [Armstrong]. Some Riley Puckett records right outside the Takoma Park Library. Down the creek, I found several Amy Smith OKehs. On Richie Avenue East, I found a Kokomo Arnold record and the Carter Family doing 'When the Roses Bloom Again in Dixieland.’ … I could go on and on like this."[4]

On one of these trips, Spottswood returned with a ’78 of Blind Willie Johnson’s “Praise God, I’m Satisfied.” Fahey was unacquainted with Blues and knew very little of the African-American musical tradition. What he heard shocked him, the effect akin to a “religious conversion.”

"I almost threw up. I said, 'Please put on some Bill Monroe records so I can get back to normal.' But here's the trick: by the end of the Bill Monroe record the Blind Willie Johnson thing was still going through my head, and I had to hear it again. This time when I heard it I started crying. I couldn't stop it. It was the most beautiful thing I'd ever heard.”[5]

Fahey grew Blues obsessed, scrounging for whatever records he could get his hands on and improvising his own open-tuned Blues pieces. Around this time, the aspiring musician began taking trips to Frederick, Maryland where he met renowned record-collector Joe Bussard. In Bussard’s basement (where he ran Fonotone Records, likely the last label to produce ’78’s[6]), the two listened to records and drank. After one night of drinking in 1959, Bussard recorded Fahey at 4 a.m. singing “everybody in this town got the blues/ here comes big Jean-Paul Sartre he got the blues” (Other verses referenced Schopenhauer, Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky; Fahey was a Philosophy major at American University)[7] It was Fahey’s first recording, and perhaps the only one to feature his singing voice.

Shortly thereafter, Fahey self-recorded what came to be recognized as the first American Primitive Guitar record, Blind Joe Death, at St. Michael's and All Angel's Church in Adelphi, Maryland. He used the wages he earned at a Langely Park Esso gas station to buy the recording equipment and had 100 LP’s printed, dispensing them around town in sometimes surreptitious ways (including stashing copies in the stacks of thrift and record stores without the consent of their owners).

Blind Joe Death bore the mark of where it was recorded. “Sligo River Blues,” the album’s penultimate truck, refers to the Sligo Creek - only a mile away from the Adelphi church where the album was taped. The song is brief and perhaps deceptively simple, built around a repetition of the same three chords. However its melody is deeply sentimental, doubtlessly meant to evoke Fahey’s wanderings as a child in the then semi-rural Maryland suburbs.

With its limited release and Fahey’s almost non-existent name recognition, his work was largely obscure. Still, it made ripples locally. University of Maryland students Robbie Basho and Max Ochs (cousin of protest singer Phil Ochs) flocked around Fahey and followed suit, advancing his style. Over the next few years, the three performed together occasionally at various venues, including churches, the now defunct Unicorn coffeehouse in Dupont Circle, and the Cabin John Recreation Center.[8] In 1963, Fahey moved to Berkeley, California on a friend’s invitation (ED Denson of Montgomery County; a prolific music manager and social justice lawyer). There, he established Takoma Records as an official label and pursued his Master’s degree in folklore, culminating in a thesis on his hero, bluesman Charley Patton (Patton’s music, as well as that of many Southern blues musicians were “rediscovered” by Fahey and released on his label to greater prominence).

In Berkeley, Fahey’s music gained greater attention, even reaching Pete Townsend in England. Townsend was an admirer of Fahey, and referred to him as “the William Burroughs of music.”[9] In 1969, he eagerly sent Fahey a copy of The Who’s Tommy; his response was polite, though unenthusiastic.

Though Townsend was likely his most famous contemporary admirer, Fahey’s music left a deep impression on a younger generation of musicians and vice versa. There was a great mutual respect between Fahey and the No-Wave experimental rockers of the 80’s, namely Sonic Youth. Front man Thurston Moore spoke of Fahey’s innovative tunings as a “real secret influence” on his group, and Fahey respected them as a refreshing and liberating force in music.[10] More recently, a 2006 Fahey tribute album featured contributions from indie-folk giants Sufjan Stevens and Devendra Banhart.[11]

Though Fahey would never again reside in Maryland, titles on his LP’s would continue to reference local geography, often in longwinded and bizarre ways. Particularly striking examples include “The Downfall of the Adelphi Rolling Grist Mill”, “The Dance of the Inhabitants of the Invisible City of Bladensburg”, and “Commemorative Transfiguration and Communion at Magruder Park”. His liner notes often elaborated on the titles, usually with absurd, pseudo-spiritual, and mostly fictitious descriptions meant to mock both “academic” folk writers as well as the emerging hippie community that flocked around Fahey (Fahey purportedly despised hippies as inauthentic). An example reads like this:

“(My) mind sees what (my) eyes think; (My) eyes know, do not know, see and see not. What is now disjunct is, will be, was, was not, neither shall be nor shall not be. Conjunct, all of these. In Riverdale and not in Riverdale, at and not at Magruder Park. I hear and do not hear the voice of the Sligo River turtle. It says and does not say. A turtle and not a turtle … But all of these, and nothing more. At Magruder Park the sun stands still, and we are together. We have not lost our way.”[12]

Other liner notes even referenced local people, including a mention of Jim Henson, once Fahey’s classmate at Northwestern High School in Hyattsville.[13]

Fahey died in Salem, Oregon on February 21, 2001 due to complications of heart surgery; he had lived between shelters and motels during his final years. One decade after his death, Blind Joe Death was added to the United States National Recording Registry as a recording of “cultural, historical, or aesthetic importance”.[14] Today, a copy is preserved in the Library of Congress, only a few miles from where it was recorded.

Footnotes

- ^ Fahey, John. How Bluegrass Music Destroyed My Life. Chicago: Drag City, 2000.

- ^ Ibid

- ^ Harrington, Richard. “John Fahey’s Brilliantly Broad Blues Pallet”. Washington Post. February 21, 2001

- ^ Dean, Eddie. “In Memory of Blind Thomas of Old Takoma”. Washington City Paper. March 9, 2001

- ^ Miller, Dale. “Reinventing the Steel String Guitar”. Acoustic Guitar. February, 1992.

- ^ Joe Bussard: King of Record Collectors. Dust-to-Digital. 2005. Today, Bussard’s collection is considered among the best in the world.

- ^ Fahey, John. “Blind Thomas Blues Part 1”. Fonotone. Tape. 1959

- ^ Dunlap, David Jr. The Cosmos Club. Washington City Paper. July 7, 2006.

- ^ In Search of Blind Joe Death: The Saga of John Fahey directed by James Cullingham. 2012

- ^ Coley, Byron. The Persecutions and Resurrection of Blind Joe Death. May 2001.

- ^ I Am the Resurrection: Tribute to John Fahey. Vanguard. 2006

- ^ Fahey, John. Voice of the Turtle (Liner Notes). Takoma Records. 1968

- ^ Fahey, John. John Fahey Visits Washington D.C (Liner Notes). Takoma Records, 1979

- ^ “Complete National Recording Registry Listing”. Library of Congress. Web. Accessed 6/26/17

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)