Capturing the Total Eclipse of 1918

On June 8, 1918, Washingtonians looked to the sky hoping to see… well… something. But, many weren’t quite sure exactly what. As the Evening Star noted:

“There was a great craning of necks on the streets. Many a citizen who had read about the eclipse and forgotten about it, wanted to know where the aeroplane was…. One woman called up The Star and wanted to know whether the Marine Band ‘is playing on the eclipse.’ A reporter carefully explained that the Marine Band sometimes played on the Ellipse.”[1]

For scientists at the U.S. Naval Observatory on Massachusetts Avenue, however, there was no confusion. The day marked an extraordinary astronomical event: a transcontinental total eclipse. For just over two hours, the moon would obscure the sun as it tracked across the sky in a path that stretched from southwestern Washington state to the east coast of Florida. It had been decades since an eclipse was visible across so much of the U.S. and, with late advances in camera technology, astronomers hoped to use the opportunity to capture photos and motion pictures of the sun’s corona, which was impossible to photograph under normal circumstances.

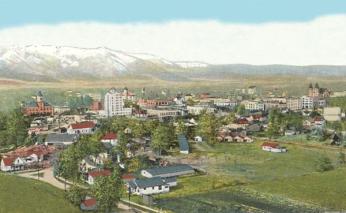

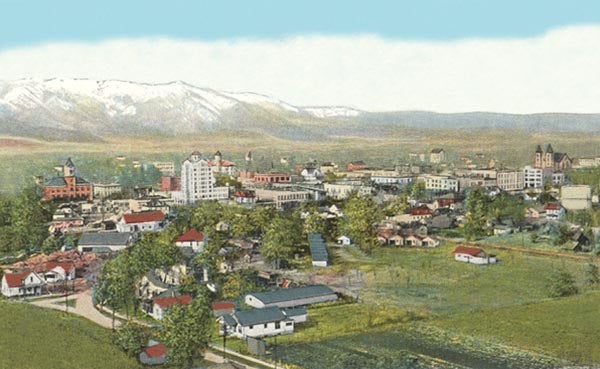

Congress had appropriated $3,500 for the Naval Observatory to document the event – no small feat considering that the country was in the midst of World War I – and preparations began months in advance. As D.C. was several hundred miles from the path of totality – and, thus, would not experience the full eclipse – the Observatory moved its eclipse operations to Baker City, Oregon, which was directly in the eclipse’s path.

Observatory astronomer John C. Hammond tapped University of Virginia professor Samuel Mitchell to direct the spectroscopic work. Mitchell left Charlottesville in April and began setting up the equipment, which included multiple different cameras. A team of astronomers from the Observatory, UVA, and Smith College soon followed to prepare for the big day.

Actually, “the big day” was really less than two minutes – 117 seconds to be exact. That was the period that the moon would fully obscure the sun over Baker City and allow the group to capture photographs of the corona. And what if clouds got in the way when the moment arrived? Months of work would be for naught.

Even if the weather cooperated, there would be other challenges. In 1918 even the most cutting-edge cameras and film could only reproduce a limited range of color. And so, the Observatory team also brought along a painter-physicist Howard Russell Baker to document the event with his brush. As Mitchell explained, “Mr. Butler has designed and for many years has practiced a shorthand method of noting both form and color. When the photographs were developed Mr. Butler will be able to add the details of the coronal filaments with the end in view of obtaining a scientifically accurate painting of the corona which will be true and not exaggerated.”[2] In effect, Butler’s job was – in less than two minutes – to accurately paint the colors he saw so that they could be merged with the photos that Mitchell’s team snapped.

Back in Washington, The Post used the astronomers’ exacting calculations about the eclipse to poke fun at the government’s recent decision to implement Daylight Savings Time. “The total eclipse of the sun forecast to occur on June 8 has been postponed for one hour. This is not the result of any error in the calculations of the astronomers nor is it due to an order by modern Joshua that the sun stand still, but is chargeable to the operations of the daylight savings law, as a result of which the clocks throughout the United States were set forward an hour.”[3]

On the morning of the eclipse, the paper printed tips from astronomer David Todd on how readers could safely view the event in D.C., where the moon would obscure 74% of the sun. It wasn’t as easy as picking up a pair of disposable glasses at the local library: “Naked eye observations of all phases of the partial eclipse are better made through neutral tint glasses, or smoked glass, which is easily prepared from lantern slide glass, or a small pane of good window glass by holding it in the flame of a lamp or candle until a black film is deposited.”[4]

In Baker City, the Observatory team watched the sky through their considerably more sophisticated lenses. As Mitchell recounted for The New York Times, it was an emotional roller coaster as the moment of totality grew near.

“The clouds became denser, and so black that the whole sun was blotted out. The hearts of the assembled astronomers sank. But soon a ray of hope came, for the clouds again thinned…. Fifteen minutes before totality the clouds thinned still more. Nature now because hushed, the birds sang their evening song, and the cocks were heard to crow.”[5]

He continued:

“Mr. Hammond gave the signal of ‘Go’ at the beginning of totality—for photographic operations to start. For 112 tense seconds, the keyed up astronomers worked with enthusiasm, the only noise that broke the stillness being the click of the plateholders as they were put in place and shutters drawn for exposures…. The members of the Naval Observatory party are tonight rejoicing in their good fortune that brought them almost clear skies.”[6]

Phew. Thanks, mother nature!

Footnotes

- ^ “Sun Partially Eclipsed in D.C.” Evening Star, June 9, 1918.

- ^ “SCIENTISTS OBTAIN GOOD ECLIPSE VIEWS: Clouds Threatened Western Observations at First, ButCleared Later. CROWDS WATCH IT HERE Perfectly Clear Sky Affords an Unrivailed Opportunity for Thousands of Gazers. Elaborate Preparations Made Photographing the Corona. Corona’s Colors in Shorthand. Clouds Obscure the Sun at Denver. No Observation at Jackson, Miss. Perfect Conditions in New York.” The New York Times, June 9, 1918.

- ^ “ECLIPSE IS ‘POSTPONED’: Changing of Clocks Will Make Sun Seem Hour Behind Schedule. BIG EVENT FOR ASTRONOMERS Scientists From Yerkes Observatory Make Denver Their Base -- 21-Inch Telescope Will Be Used for Viewing Corona -- Lack of Apparatus Due to War.” The Washington Post, May 12, 1918. In 1918, most Americans went to bed earlier and rose earlier than they do today. Thus, DST was not widely popular when it was signed into law on March 19, 1918. Following World War I, it was repealed and became a local option for several decades. For more see the WebExhibits article about Daylight Savings Time.

- ^ “SUN TO BE IN ECLIPSE: May Be Observed Here From 6:41 P.M. Until Darkness. STARTS ON JAPANESE ISLAND Sweeps Across the Pacific to Aberdeen, Wash., and Thence Through the United States to Orlando, Fla. -- U.S. Making Observations. Explained by Prof. David Todd. ” The Washington Post, June 8, 1918.

- ^ “SCIENTISTS OBTAIN GOOD ECLIPSE VIEWS: Clouds Threatened Western Observations at First, ButCleared Later. CROWDS WATCH IT HERE Perfectly Clear Sky Affords an Unrivailed Opportunity for Thousands of Gazers. Elaborate Preparations Made Photographing the Corona. Corona’s Colors in Shorthand. Clouds Obscure the Sun at Denver. No Observation at Jackson, Miss. Perfect Conditions in New York.” The New York Times, June 9, 1918.

- ^ “SCIENTISTS OBTAIN GOOD ECLIPSE VIEWS: Clouds Threatened Western Observations at First, ButCleared Later. CROWDS WATCH IT HERE Perfectly Clear Sky Affords an Unrivailed Opportunity for Thousands of Gazers. Elaborate Preparations Made Photographing the Corona. Corona’s Colors in Shorthand. Clouds Obscure the Sun at Denver. No Observation at Jackson, Miss. Perfect Conditions in New York.” The New York Times, June 9, 1918.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)