The Biggest Cheese in Washington: Mammoth Cheeses in White House History

While Presidents of the United States have received all different kinds of honors and gifts throughout the years, there is one particular 19th-century trend of presidential gift-giving that stands out…or maybe stands alone.

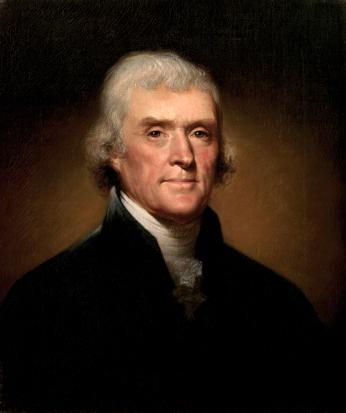

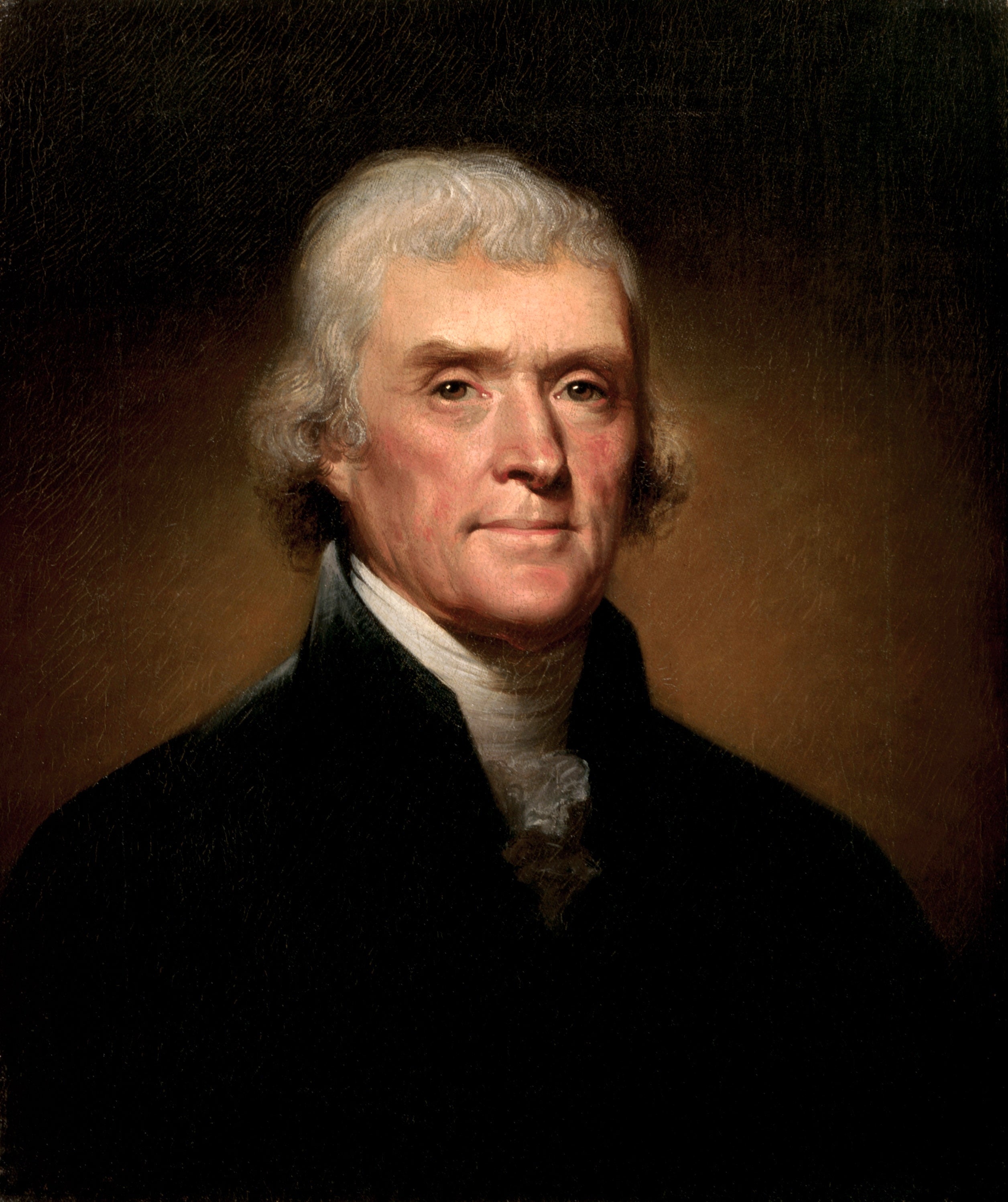

Giant wheels of cheese have appeared at the White House multiple times in presidential history, starting in 1801 when Thomas Jefferson was gifted the 4 foot-wide, 17 inch-high, 1,235 pound Cheshire “Mammoth” Cheese from the citizens of Cheshire, Massachusetts.[1] The idea for this cheese came from Elder John Leland, a Baptist from Cheshire, who supported the Democratic-Republican President in a decidedly Federalist, and non-Baptist, Massachusetts. Leland wanted to celebrate Jefferson’s presidential win over Federalist John Adams by making a grand statement about political and religious freedom and marking the return of American republicanism. He initiated this in July 1801, when he pulled together members of his Baptist church to produce an enormous cheese for the new President.[2] The cheese was made of milk from 900 strictly Republican cows, and “was produced by the personal labor of Freeborn Farmers, with the voluntary and cheerful aid of their wives and daughters, without the assistance of a single slave.”[3]

Once finished, they engraved the giant wheel of cheese with the patriotic motto displayed on Jefferson’s personal seal: “Rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God.”[4]

Come winter, the cheese made the three-week journey from Massachusetts to Washington in a sleigh pulled by six horses, and finally arrived on December 29, 1801. On New Year’s Day, 1802, Jefferson stood in the doorway of the White House to receive what the Nation was calling “Mammoth Cheese.”

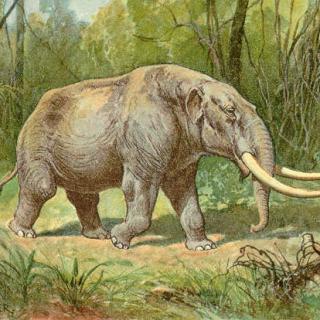

The term “mammoth” originated when Charles Willson Peale, painter and naturalist, started displaying enormous, New York-discovered mammoth bones in his Philadelphia museum. The American people became mammoth obsessed and started to use the term “mammoth” as an adjective to describe anything of remarkable size. The term slowly became more political when Jefferson, a naturalist himself, donated money to Peale to assist in his mammoth research; Federalists believed this act to be a waste of money, and consequently started to use the term “mammoth” negatively towards anything in reference to Jefferson.[5]

The cheese, therefore, earned its name, “Mammoth Cheese,” from the Federalist press who thought the idea of an enormous cheese for the President was ridiculous. The Republican press latched onto the name “Mammoth Cheese” as well, but used the term endearingly—soon enough, the name had stuck with the American public and they excitedly awaited the chance to see the monstrous cheese as it passed through on its way to Washington.

After receiving the cheese on January 1, 1802, Jefferson paid Leland $200, in order to stay in line with his newly established practice of refusing to accept gifts while President. The cheese then resided in the East Room of the White House for what is believed to be the better part of the next three years; the cheese was present at the following New Year’s Day 1803, portions were distributed at Washington Independence Day gatherings in 1802 and 1803, and a large piece was reported to have been presented to Congress in March 1804.[6] While much of the cheese was eaten in the three year period, a significant amount of it spoiled and became maggot infested.[7] Conflicting accounts suggest that the remaining parts of the cheese were either served as late as New Year’s Day 1805, or just dumped right into the Potomac River.[8]

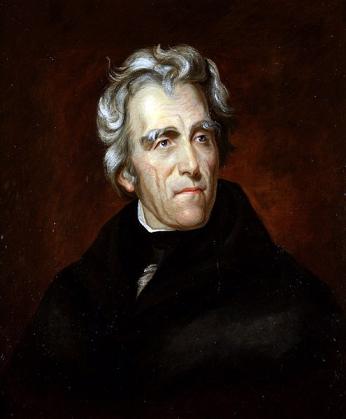

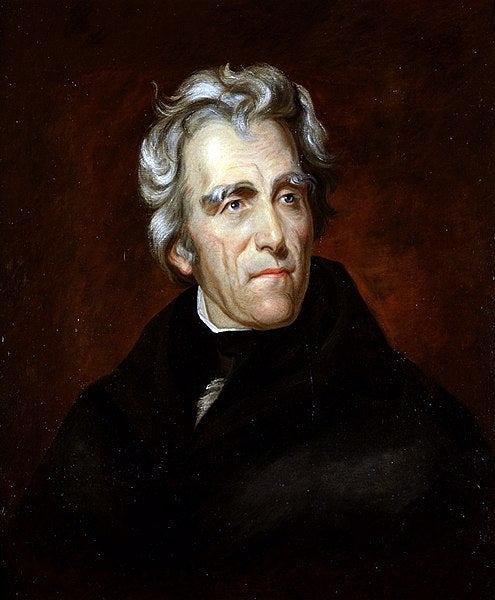

Funny enough, Jefferson’s Mammoth Cheese was not the last one to enter the White House, and the next one was even more mammoth. The next cheese was gifted to Andrew Jackson in 1835 by a group from New York State. According to Benjamin Perley Poore’s 1886 book Perley’s Reminiscences of Sixty Years in the National Metropolis, “Jackson’s admirers thought that every honor which Jefferson had ever received should be paid him, so some of them, residing in a rural district of New York, got up, under the superintendence of a Mr. Meacham, a mammoth cheese for ‘Old Hickory.’”[9]

Colonel Thomas Meacham of Oswego County, New York, didn’t like Andrew Jackson and had supported Henry Clay in the Presidential Election of 1832, but he hoped that the giant cheese would advertise the “exceptional industry and ingenuity” of his home state of New York.[10]

Meacham’s cheeses were ornately decorated with customized paintings and mottos, and created with the “intention of pomp and circumstance.”[11] He did not want the presentation of this cheese to be any different, and even made an 800 pound wheel of cheese for Vice-President Martin Van Buren in addition. His final 1835 product for President Jackson was an impressive 1,400 pound wheel of cheddar that arrived in Washington in a cart pulled by a fleet of 24 horses; the mammoth cheese then sat in the White House foyer for the next two years.

Jackson’s presidency was the first time that the East Room of the White House was furnished and regularly used by its residents; Congress appropriated the necessary funds, and soon the room was adorned with lemon yellow wall paper, decorations in glass, mahogany and silk, and dotted with 22 spittoons to serve the national habit of chewing tobacco.[12] Equipped with the exquisite, newly furnished East Room, President Jackson began a tradition of opening up the White House for extravagant parties, which the Washington public was welcome, and encouraged to attend.

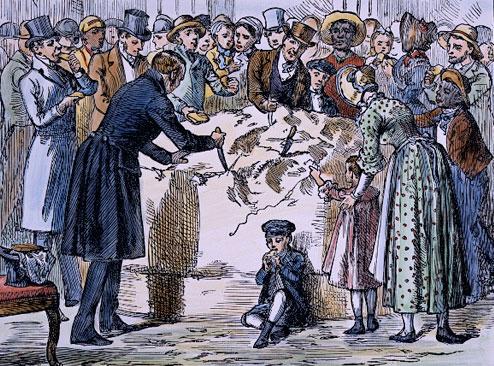

No party was as memorable, however, as the celebration he threw in honor of George Washington’s birthday on February 22, 1837—which was also the last time Jackson would receive people at the White House. For the occasion, Jackson had the two-year-old, viciously fragrant (Washingtonians could smell it blocks away from the White House) mammoth cheese hauled from the foyer into the East Room, and invited citizens from all over Washington to come to the White House and help eat it. Washingtonians did not miss the chance to help consume the presidential cheese, and it is rumored that the party was so crowded that “people who could not fit through the doors were climbing in through the windows.”[13] A crowd of 10,000 turned out and “hacked” at the cheese—eating pieces, and taking large hunks away with them as well.[14] In just two hours, the entire 1,400 pound wheel of cheese had been demolished, with only a small piece saved for Jackson. “The air was redolent with cheese, the carpet was slippery with cheese, and nothing else was talked about at Washington that day.”[15]

Jackson’s great cheese extravaganza left the East Room, and really the entire White House, reeking of aged cheese odor. So much so that when Van Buren was inaugurated as President just two weeks later, he had to spend days airing out the house, and scraping cheese curds out of the carpet; this subsequently led him to ban the serving of all food at White House receptions.[16] On January 24, 1838, the wife of Massachusetts senator John Davis wrote:

“The White House has been put in order by its present occupant, and is vastly improved — [Van Buren] says he had a hard task to get rid of the smell of cheese; and in the room where it was cut, he had to air the carpet for many days; to take away the curtains and to paint and white-wash before he could get the victory over it. He has another cheese like that which General Jackson had cut, and says he knows not what to do with it.” [17]

Thankfully, the White House, and the entire neighborhood surrounding 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, has aired out since the cheesy extravaganzas of the 19th century, but the stories of the great presidential mammoth cheeses will continue to linger on for cheddar or for worse.

Pop Culture Side Note: We would be remiss (or maybe reswiss) not to mention that true fans of The West Wing might remember fictional White House chief of staff Leo McGarry speaking the words “Andrew Jackson, in the main foyer of the White House, had a two-ton block of cheese. It was there, for any and all who were hungry, it was there for the voiceless” (Season 2, Episode 16, “Somebody's Going to Emergency, Somebody's Going to Jail”). McGarry was trying to invigorate an exasperated White House team by explaining how Jackson used the cheese as a symbol for open communication and populism. It was actually the second time he spoke on the subject. There was an equally amusing scene featuring McGarry discussing Jackson’s mammoth cheese in Season 1 (Episode 5, “These Crackpots and These Women”). While Leo’s take on the history was not entirely accurate, it’s still fun to know that Jackson’s cheesy legacy lives on.

Footnotes

- ^ “What’s More Presidential Than a Gift of Big Cheese? | National Geographic | The Plate.” 2015. February 23, 2015. http://theplate.nationalgeographic.com/2015/02/23/whats-more-presidenti….

- ^ “A Tale of a Giant Cheese, a Loaf of Bread and the First Amendment - National Constitution Center.” National Constitution Center – Constitutioncenter.org. Accessed November 21, 2017. https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/a-tale-of-a-giant-cheese-and-the-fi….

- ^ “I. From the Committee of Cheshire, Massachusetts, [30 December 1801],” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified November 26, 2017, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-36-02-0151-0002. [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 36, 1 December 1801–3 March 1802, ed. Barbara B. Oberg. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009, pp. 249–250.]

- ^ “What’s More Presidential Than a Gift of Big Cheese? | National Geographic | The Plate.” 2015. February 23, 2015. http://theplate.nationalgeographic.com/2015/02/23/whats-more-presidenti….

- ^ “A Tale of a Giant Cheese, a Loaf of Bread and the First Amendment - National Constitution Center.” National Constitution Center – Constitutioncenter.org. Accessed November 21, 2017. https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/a-tale-of-a-giant-cheese-and-the-fi….

- ^ “Founders Online: Editorial Note: Presentation of the ‘Mammoth Cheese.’” Accessed November 27, 2017. http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-36-02-0151-0001.

- ^ “What’s More Presidential Than a Gift of Big Cheese? | National Geographic | The Plate.” 2015. February 23, 2015. http://theplate.nationalgeographic.com/2015/02/23/whats-more-presidenti….

- ^ “Founders Online: Editorial Note: Presentation of the ‘Mammoth Cheese.’” Accessed November 27, 2017. http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-36-02-0151-0001.

- ^ Poore, Benjamin Perley. 1886. Perley’s Reminiscences of Sixty Years in the National Metropolis. Hubbard brothers. 196.

- ^ “What’s More Presidential Than a Gift of Big Cheese? | National Geographic | The Plate.” 2015. February 23, 2015. http://theplate.nationalgeographic.com/2015/02/23/whats-more-presidenti….

- ^ SkochdopoleE. 2017. “The Big Cheese: Presidential Gifts of Mammoth Proportions.” Text. January 44–44, 2017. http://npg.si.edu/blog/big-cheese-presidential-gifts-mammoth-proportions.

- ^ “An Essay on ‘The Great Cheese’ by Peter Waddell.” WHHA. Accessed November 21, 2017. https://www.whitehousehistory.org/the-great-cheese-jacksonian-democracy….

- ^ SkochdopoleE. 2017. “The Big Cheese: Presidential Gifts of Mammoth Proportions.” Text. January 44–44, 2017. http://npg.si.edu/blog/big-cheese-presidential-gifts-mammoth-proportions.

- ^ Poore, Benjamin Perley. 1886. Perley’s Reminiscences of Sixty Years in the National Metropolis. Hubbard brothers. 196-197.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “What’s More Presidential Than a Gift of Big Cheese? | National Geographic | The Plate.” 2015. February 23, 2015. http://theplate.nationalgeographic.com/2015/02/23/whats-more-presidenti….

- ^ “Mr. Andrew McF. Davis Read Extracts from a Letter Written by His Mother, the Wife of John Davis — Then United States Senator from Massachusetts — to a Kinswoman, the Wife of Colonel Joseph Davis of Northborough, Massachusetts.” 1838. Colonial Society of Massachusetts. January 24, 1838. https://www.colonialsociety.org/node/243.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)