The Congressional Library’s Underground Book Tunnel

By 1875, the ever-expanding Congressional Library in the Capitol Building had outgrown its shelf space, which forced librarians to store incoming books, maps, music, photographs, and documents in stacks on the Library floor, as well as in dozens of separate locations throughout the Capitol—including cellar crypts.[1] Eventually, Congress approved a plan to move its Library into a new structure that would be built across from the Capitol, and by the end of the summer of 1897, all 800,000 books and other documents had been moved into the newly opened Library of Congress building, which is known today as the Jefferson Building.

While the books now had plenty of space, a new challenge presented itself: how would the congressmen have easy access to their library if it was now a quarter of a mile away? Surely the congressmen would not be expected to go on a half-mile walking excursion every time they needed a book. The solution was a technological creation that seems futuristic at the very least: a special underground tunnel full of conveyor belts and pneumatic tubes that connected the two buildings, and had books zooming to and fro under First Street SE for nearly the next century.

The Army Corps of Engineers, a US federal agency consisting of civilian and military personnel, was put in charge of the construction of the book tunnel.[2] Heading the project was General Thomas L. Casey, Chief of Engineers, who had previously been tasked with overseeing the completion of the Washington Monument. While Casey was in charge of the entire Library of Congress construction, he also oversaw the construction of the tunnel that was to be dug between the new Library and the Capitol. The tunnel construction project was nestled in with the $900,000 budget appropriated by Congress in March 1895 for the construction of the Library, and work began on the tunnel in August.[3]

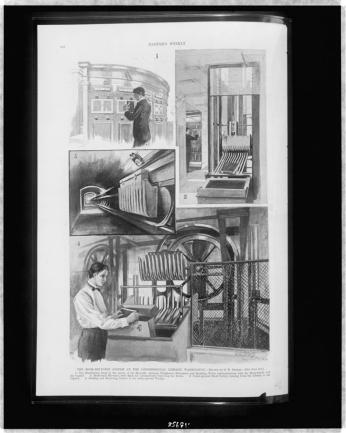

The tunnel, built of brick and measuring six feet high and four feet wide, had one terminal directly underneath the distribution desk in the Library, and another located in the Capitol midway between the Senate and the House.[4] Inside, it contained pneumatic messenger tubes, telephone wires, and an extensive “book-carrying apparatus.”[5] This book-carrying apparatus was a work of technological amazement and was described as the following in the 1901 Librarian of Congress Annual Report:

“The carrier to the Capitol consists of a small, flexible, endless wire cable running over large sheaves at either extremity of the route, and having attached to it at opposite ends of the loop grooved trolleys which run between a pair of rails parallel to each other and to the cable throughout the whole course of a quarter of a mile, including that over and under the sheaves. To each of the two trolleys is hung a carrier large enough to hold a bound volume of newspapers, or a leather pouch, of similar shape and capacity, for smaller books and other matter. The carriers consist of a set of deep parallel hooks similar to the hanging human hand with the fingers turned upwards nearly to the top. Being hung from the top like a pendulum, it travels always in an upright position. Its loads are therefore taken on by passing upward through a corresponding toothed trough, and delivered by passing downward through a toothed rack.” [6]

This apparatus could move books at approximately 600 feet per minute, meaning that a book could arrive at the Capitol approximately three minutes after leaving the Library.[7] In addition to the cables, conveyor belts, and tubes, the tunnel was also equipped with telephone wires to allow for the “rapid transmission” of messages between the book requestor in the Capitol, and the librarian tasked with fetching the book in the Library.[8] When Congress was in session, members could take advantage of this futuristic contraption to request and receive books needed for reference in debates and committees.

According to Mary Simmerson Cunningham Logan, a contemporary writer from the time, the high-tech book delivery system improved everyday work for many congressmen:

“A Congressmen or Senator can obtain a volume now in less time than he could when the books were in their old quarters in the Capitol. If in the midst of a speech it occurs to a Senator that he needs a certain book or the file of a certain newspaper, he has but to call a page, whisper his wish, and before he has delivered many more sentences, the page returns with the book or file.” [9]

Not every congressman agreed with Logan about the so-called convenience of the contraption, however. In a January 1900 edition of The Washington Post, multiple congressmen complained about the time that it took to receive books from the new Congressional Library.

“Representative Cummings, of New York, said that in the old days one could get books and newspapers within five or six minutes from the old Congressional Library, this prompt service being an important factor in debate, when one wanted information immediately. Some Member said that the books could be had through the tunnel in five or six minutes, and Mr. Cummings found an opportunity to put it to practical test. Representative Moody, of Massachusetts, as it happened had just ordered a copy of Henry Adams’ history of the United States. He received word after twenty-five minutes that it was out of the library, to which fact he testified before the house.” [10]

Additionally, Representative Cannon, of Illinois, remarked that “often the wrong book came, because the clerk at the other end did not know exactly what information the Member wanted,” and that these misunderstandings could be avoided if the Members had more personal contact with the Librarians—a dilemma that would seem years ahead of its time.[11]

So are books still whizzing underneath First Street today? Unfortunately no. The Capitol portion of the book tunnel was destroyed around 2000 to make way for the new underground Capitol Visitors’ Center. In an ironic twist, yesterday’s tomorrow didn’t hold up to the force of digital resources, so today’s Library of Congress librarians have to deliver physical books by hand.

Footnotes

- ^ Cole, John Y. 1972. “Library of Congress Information Bulletin.”

- ^ “About -- Headquarters U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.” Accessed March 25, 2018. http://www.usace.army.mil/About/.

- ^ United States Department of the Treasury Division of Bookkeeping and Warrants. 1896. Digest of Appropriations for the Support of the Government of the United States on Account of the Service of the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1896 and of Deficiencies for Prior Years Made by the Third Session of the Fifty-Third Congress. U.S. Government Printing Office. 47.

- ^ Logan, Mary Simmerson (Cunningham). 1901. Thirty Years in Washington of Life and Scenes in Our National Capitol. Hartford, Conn., A.D. Worthington & co. http://archive.org/details/thirtyyearsinwa00loga. 435.

- ^ Library Journal. 1896. Vol. 21. New York: Publication Office. 106.

- ^ Annual Report of the Librarian of Congress for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1901. 1901. Washington, D.C., United States: Government Printing Office. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/coo.31924112523802. 356-357.

- ^ Logan, Mary Simmerson (Cunningham). 1901. Thirty Years in Washington of Life and Scenes in Our National Capitol. Hartford, Conn., A.D. Worthington & co. http://archive.org/details/thirtyyearsinwa00loga. 435.

- ^ United States Department of the Treasury Division of Bookkeeping and Warrants. 1896. Digest of Appropriations for the Support of the Government of the United States on Account of the Service of the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1896 and of Deficiencies for Prior Years Made by the Third Session of the Fifty-Third Congress. U.S. Government Printing Office. 47.

- ^ Logan, Mary Simmerson (Cunningham). 1901. Thirty Years in Washington of Life and Scenes in Our National Capitol. Hartford, Conn., A.D. Worthington & co. http://archive.org/details/thirtyyearsinwa00loga. 435.

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1900. “BOOKS BY THE TUNNEL: Members State That the Volumes Return Slowly.,” January 9, 1900. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Ibid.

![“Washington D.C., Library of Congress 1897-1910.” (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Detroit Publishing Co., Copyright Claimant, and Publisher Detroit Publishing Co. Washington, D.C., Library of Congress. District of Columbia United States, Washington D.C, None. [Between 1897 and 1910] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016796190/](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/4a28645v.jpg?itok=WxMtjKxx)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)