WHFS Sells Out the Deejay

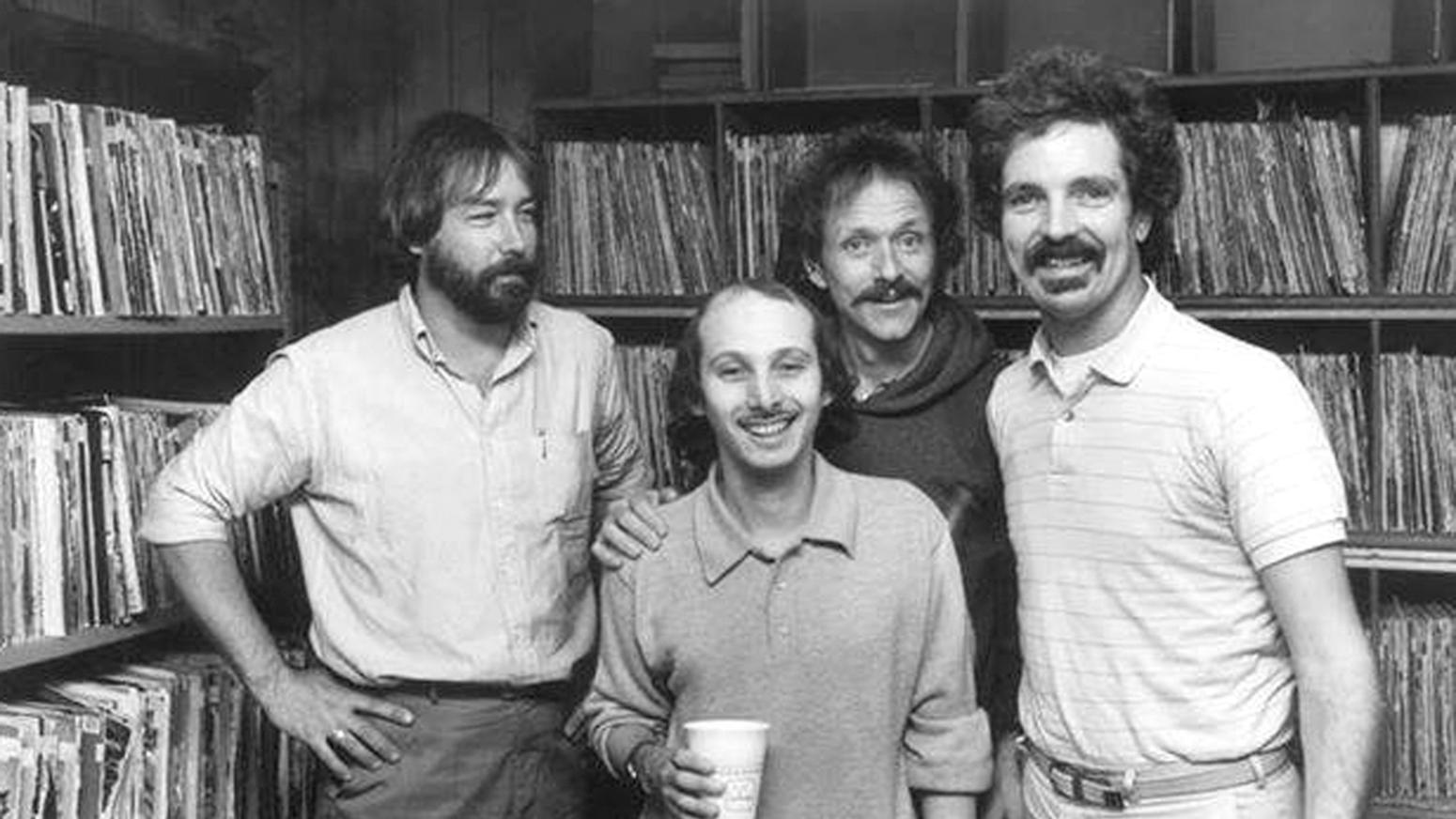

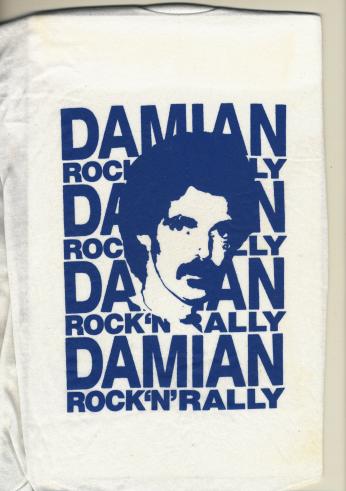

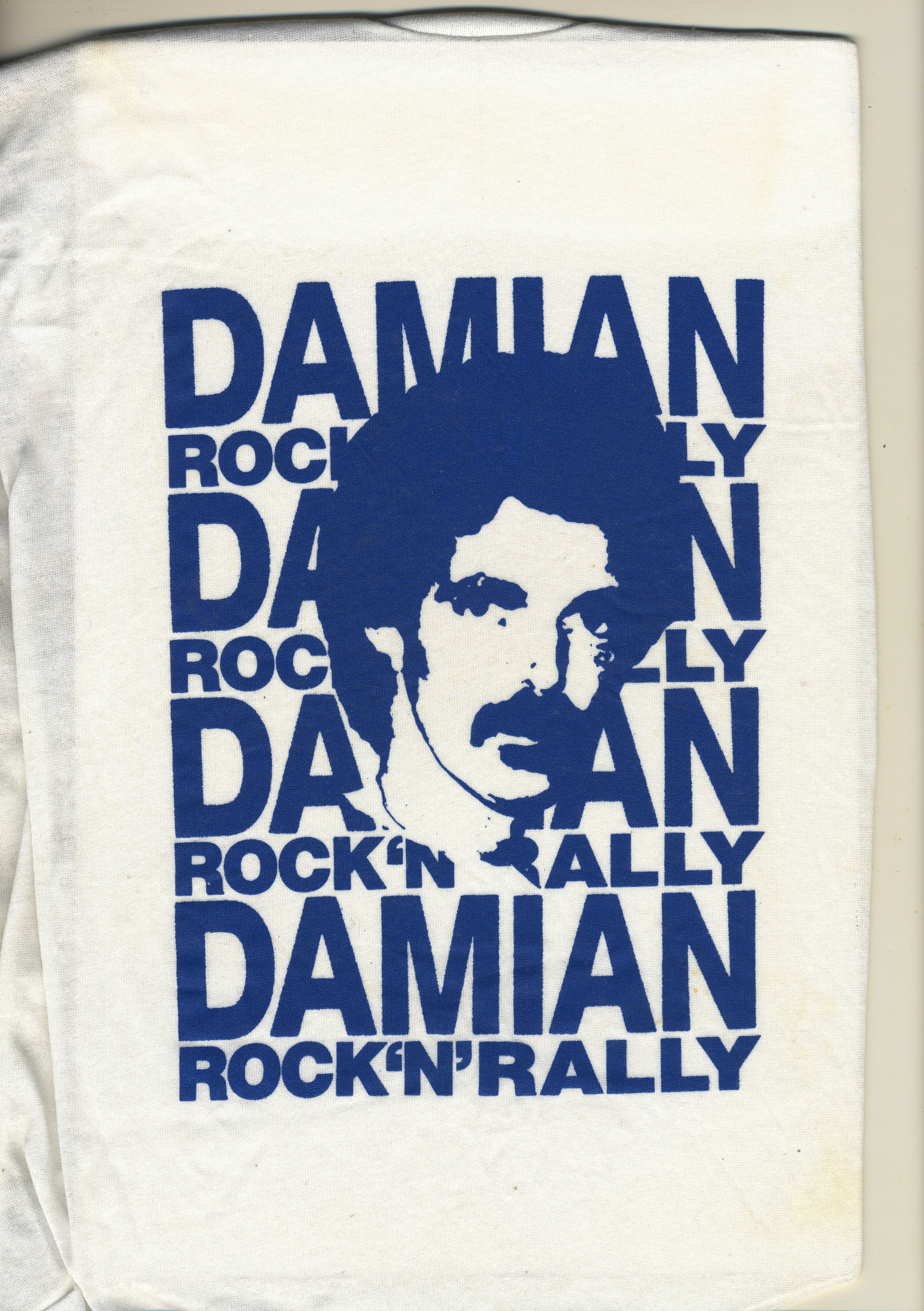

On June 11, 1989, 8,000 people crowded into a Wheaton parking lot in front of Joe’s Record Paradise for what the Washington Post described as, “a grass-roots rebellion,” to protest the removal of beloved WHFS FM 99.1 deejay, Damian Einstein, from the airways. Attendees of what store owner Joe Lee dubbed “Damianfest,” included die-hard fans who fell in love with Damian’s expansive musical tastes which he revealed to listeners on his daily 9am-Noon slot, WHFS colleagues, and artists who owed some of their success to Damian’s ear for talent.[1] Technically, according to new WHFS general manager, Alan Hay, Damian had not been fired so much as a “promoted” to an off-air role. However, to the horde gathered in Wheaton – and to thousands of dedicated listeners across the DMV – the move suggested something more ominous.

Standing in front of the raucous crowd, Damian’s former colleague Josh Brooks read aloud a letter he had written to Hay:

“Without [Damian] on the air, WHFS starts to lose its uniqueness and begins to seem ordinary. And when listeners no longer perceive WHFS as unique you might as well ‘promote’ the rest of the staff, bring in some golden-throated personalities and have the record company promo men do the programing!”

He continued, “It is possible you will attract new listeners by making this move but you can be sure they won’t be the bumper-stickered, t-shirted, music-loving, loyal fanatics that feel they at WHFS are part of one big family!”[2]

Even Brooks may not have realized how prophetic his words would turn out to be. Since its founding in the 1960s, WHFS’s airwaves had been centered on the freewheeling deejay. Deejays would regularly “promote local bands, eschew pater and gimmicks and play a mix of new and vintage rock, reggae, jazz, blues, folk, zydeco, or just about anything that pops into the head of the deejays or listeners.”[3] The result was a unique, decidedly un-corporate sound.

However, at the behest of the station’s new owners – the large conglomerate Duchossois, Inc. – Alan Hay brought a new model to WHFS, which was becoming increasingly common across the country. Hay’s model was predicated on “narrowcasting” to a specific audience, and featured on-air personalities with polished voices repeatedly playing the “hits.” Damian, with his “mash-earnest, labored, and unvarnished” delivery, and his penchant to play whatever music he wanted, did not fit.[4]

The next decade would be a roller-coaster ride for the station and its listeners. Catching the wave of suddenly-mainstream grunge music, WHFS took off in popularity. Ratings soared as deejays began jamming the repeat button more frequently than ever, playing the same Pearl Jam, Cranberries, Nirvana, and other alternative tracks over and over again.[5] Ironically, grunge was the sort of hidden sound which WHFS deejays like Damian might have prided themselves in introducing to listeners in an earlier time. However, with the explosion of Nirvana’s Nevermind album in 1992, once proudly alternative music started to be played with regularity on more mainstream radio stations.

In addition to narrowing WHFS’s playlist, Hay introduced new on-air personalities like Pat Ferrise. David Daley, writing for the Washington City Paper, described Ferrise as “a model of grace and humor,” who had “a singsong voice and a tendency to enunciate every syllable and to dissolve the end of sentences into gales of laughter.” Ferrsie even admitted to the Washington City Paper that he was constrained by upper management and “can’t always play his favorite songs on the air.”[6] WHFS experienced a ratings and popularity boom, grabbing the attention of the Rolling Stone, which declared WHFS one of the top five most influential progressive rock stations in the country.[7]

Off the air, Hay raised the station’s profile by introducing a music festival dubbed HFStival in 1990. After two years as a relatively small-scale event held at Lake Fairfax Park in Northern Virginia, and Upper Marlboro, Maryland (in 1992), HFStival moved to bigger digs in D.C. in 1993.[8]

An annual draw for MTV’s television cameras for almost a decade, the show featured nationally acclaimed artists playing alongside local acts to a sold-out crowd in Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium. Each spring, it was quite a scene. As security guard Jim Davidson told the Washington Post at the 1994 event, “it’s raining people.” The people which Davidson was referring to were largely teens who would congeal into massive mosh pits, slamming and bumping to rousing performances from headliners like the Meat Puppets, Afghan Whigs, and the Violent Femmes.[9]

But even as the ratings were taking off and HFStival was growing year by year, some longtime fans were turned off by the growing corporate nature of the WHFS brand. As progressive rock fan and talent buyer for The Black Cat Club, Chris Thompson, decried, reflecting on his experience at the 1994 festival, “’I’ve been here for two hours and it sucks. What are these people doing here?’” and after pointing to a “huge inflatable Miller Beer can,” he said “‘that pretty much sets the tone, doesn’t it.’”[10]

The commercialization of WHFS was, in part, driven by the rise of national radio conglomerates. In 1993, Duchossois Inc. sold WHFS to Liberty broadcasting group, which was an ambitious cooperation with aims of dominating the mid-Atlantic radio market.[11] Just three years later, in 1996, the Federal Communications Commission loosened regulations allowing companies to own a greater share of the nation’s radio stations. This move opened the door for Westinghouse, owner of CBS radio and the largest radio broadcaster in the country, to purchase Liberty which, by 1996, had grown to the second largest broadcasting company in the nation. Cooperate consolidation completely reshaped the D.C.-area radio experience with four national corporations, Chancellor, CBS, Disney, and Radio One owning eighteen of the top twenty-two radio stations in the Washington market by 1997.[12]

Noting the shift, Marc Fisher of the Washington Post lamented the new normal where station “owners believe they can no longer afford to leave their fate to the personal tastes of a handful of folks hired for their mellifluous voices. And executives are loath to try out unusual programming, preferring to nip at the edges of their competitors’ audiences with formats that-despite different labels-all play Jewel, Sheryl Crow, and Live.[13]”

Jake Einstein, who had co-owned and managed WHFS from 1968 until selling in the early 1980s, described a D.C. radio environment to the Washington Post where “stations are doing the same thing-corporate rock, 35 different songs a day. It’s like fast food, but its fast food radio.”[14]By the mid ‘90s, the grunge movement, which was pivotal to WHFS meteoric success earlier in the decade, began to peter out following the death of Nirvana front-man Kurt Cobain, the relative flop of Pearl Jam’s album Vitalogy, and the breakup of Soundgarden. The declining popularity of grunge began to expose the weaknesses in WHFS’s now mainstream format. As twenty-five year old Kurt Richer, complained to the Post in 1995: “Both 101 and HFS play the music I listened to in college when it was alternative, but now its mainstream pop music for kids in junior high…. both [stations] have turned very commercial and I don’t like that. It’s the same as the Top 40 but the sound’s changed. It’s gone from Michael Jackson in the 80s to Pearl Jam in the 90s.”[15]

Between 1996 and 1998, WHFS’s listenership declined by a third, and by the turn of the century, many WHFS listeners were turning to internet radio to find the noncommercial sound which WHFS used to pride itself on providing.[16]The station was unsustainable.

On January 12, 2005, WHFS – which, by then was owned by Infinity Broadcasting, a branch of Viacom and the largest radio conglomerate in the country – departed from the Washington, D.C. airways. The end came abruptly. At noon, after the final chords of Jeff Buckley’s 1995 hit, “Last Goodbye,” faded, listeners heard an energetic greeting in Spanish:

Transmitiendo desde la ciudad capital de America: "Esta! Es! Tu! Nueva! Radio!"

"Transmitting from America's Capital City: This! Is! Your! New! Radio!"

The format change and rebranding to “El Zol” was not only a reflection of progressive rock’s declining popularity in D.C. and around the country, but also a testament to the growth of the Spanish speaking audience in Washington. Justifying the transition, Infinity spokeswoman Karen Mateo relayed to the Post that “we realized that there was a void there for approximately 10 percent of the market.”[17]

Reporting on WHFS’s departure, Marc Fisher asked “when WHFS began, to excuse the expression, suck.”[18]For Josh Brooks and others, the removal of Damian from the airways in 1989 might have been that moment – or at least the first sign of the transformation. Railing against the change initiated by Alan Hay back then, Brooks warned that the changes “sound reasonable if you are dealing with a normal radio station competing for a normal audience. WHFS and its listeners, however, are anything but normal! … WHFS listeners tune in to hear a variety of good music that will both entertain them and broaden their cultural horizons. They want a friend they can trust to guide them through the jungle of commercial hype, to help them to discover the real music they will love and cherish their whole lives!”[19]

For many in Washington, the loss of WHFS was like losing a trusted friend.

Footnotes

- ^ Manuel Roig-Franzia, “Soul Survivor: WRNR’ s Damian Endures as a Music Icon after 30 Years of Radio’ s Mood Swings and a voice-Altering Accident Damian the Deejay: The Show Must Go on Protests, Legal Rulings and Fan Ingenuity have Helped Keep Revered Radio Legend on Air for Three Decades,” The Washington Post, December 13, 2001, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post; . Hank, Steuver, “The Silence of Damian the Deejay: At WHFS, Protest Over an Off-Air ‘Promotion’ Damian Einstein Deejay.” Washington Post, August 16, 1989, ProQuest: Historical Newspapers.

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8OHs70aZiHY.

- ^ Charles Babington, “Snap, Crackle & Rock: WRNR Has a Weak Signal, but Its Following is Growing Strong,” Washington Post, May 24, 1995, ProQest Historical Newspapers.

- ^ Richard Leiby, “Notalgia Station: The Music of the Boomers' Prime Is Saturating Washington,” The Washington Post, January 6, 1994, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post; Marc Fisher, “The Listener: DC Radio, Between Rock and a Soft Place,” Washington Post, April 22, 1997, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post; Richard Neer, FM: The Rise and Fall of Rock Radio, (New York: Villard, 2001), sections 42 and 43; Manuel Roig-Franzia, “Soul Survivor,” ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ Robert Hilburn, ‘The Rise and Fall of Grunge,” Los Angeles Times, May 31, 1998, http://articles.latimes.com/1998/may/31/entertainment/ca-54992; Richard Leiby, “An Alternative Attitude: Station Chisels a Niche Between the New Rock and Its Old Hard Place,” Washington Post, December 16, 1995, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ David Daley, “It’s Pat!,” Washington City Paper, July 26, 1996, https://www.washingtoncitypaper.com/arts/article/13011213/its-pat.

- ^ “An Alternative Attitude: Station Chisels a Niche Between the New Rock and Its Old Hard Place,” Washington Post, December 16, 1995, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ Jeffrey Yorke, “A Big Blizzard of Interference,” Washington Post, January 9, 1996, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ Eric Brace, Julian Rubenstein, “HFStival’s Alternative to Adulthood: From Moshers to Meat Puppets, RFK Rocks,” Washington Post, May 16, 1994, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Jeffrey Yorke, “On the Dial: WHFS, WXTR to Team Up, The Washington Post, September 28,1993, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Marc Fisher, “3 More Area Radio Stations Change Hands: Sales will add to Conglomerate Trend,” Washington Post, April 15, 1997, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ Jeffrey Yorke, “Damian Takes Alternative Road,” The Washington Post, September 20, 1994, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ ibid.

- ^ Frank Ahrens, “The Radio Waves of the Future: Internet Stations Give Listeners a New Way to Tune in,” The Washington Post, January 21, 1999, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ Teresa Wiltz and Paul Farhi, “WHFS Changes its Tune to Spanish: Alternative Rock Pioneer Targets Latino Audience,” Washington Post, January 13, 2005, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A4390-2005Jan12.html.

- ^ Marc Fisher, “In a Way, WHFS was Already Gone,” Washington Post, January 16, 2005, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A12756-2005Jan15.html.

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8OHs70aZiHY

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)