The Fire of Norman Morrison

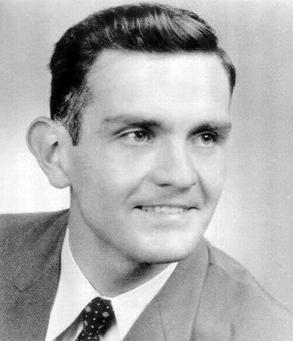

Dusk was approaching when Norman Morrison pulled into the Pentagon parking lot on November 2, 1965. Parking his two-tone Cadillac in the lot, he walked toward the north entrance, carrying his 11-month old daughter, Emily, and a wicker picnic basket with a jug of kerosene inside. Reaching a retaining wall at the building’s perimeter, the 31-year-old Quaker from Baltimore climbed up and began pacing back and forth. Around 5:20 pm, he yelled to Defense Department workers who were leaving the building.

Then, the unthinkable.

As U.S. Army Maj. Richard V. Lundquist told the Evening Star, “He suddenly appeared to light up and burst completely into flame, silhouetted against the dusk. Some people yelled at him ‘drop the baby’… the next thing I knew, he went over the wall and people were beating out the flames with their coats. I scrambled up the wall with several others and picked up the baby.”[1]

Thankfully, though Emily’s clothes were soaked in the kerosene that her father had used to turn himself into a human torch, she was unharmed. The same could not be said for Norman. Flames engulfed his body, soaring 12 feet into the air. According to horrified witnesses, Morrison attempted to speak as he burned but they could not make out what he was saying. He burned to death just beneath Defense Secretary Robert McNamara’s third floor office window.

Ambulances arrived promptly and whisked Morrison to the nearby Fort Myer dispensary, but it was too late. With second and third degree burns covering 70% of his body, he could not be saved.

Norman Morrison’s wife, Anne, first learned of her husband’s suicide when a news reporter phoned their home in Baltimore. Upon realizing she didn’t know what happened, the man told her that Norman had been involved in “a form of protest” in Washington, and suggested that she call Fort Myer. “Intuitively, I knew he hadn’t survived,” Anne recalled later.[2]

She made the 40 mile drive to Fort Myer with two friends where she collected baby Emily, but declined to speak to the press. At the Pentagon and around the country, the obvious question hung in the air, thick like kerosene:

Why?

Details began to emerge within hours. Investigators found several clues in Morrison’s clothing, including an invitation to a Quaker meeting, with the question “How Can We Prevent World War III” penned on the back.[3] Another handwritten statement read “As we go stronger materially we get weaker morally. Few would disagree.”[4]

Later that evening, a family friend gave a statement on behalf of Anne: “Norman Morrison has given his life today to express his concern over the great loss of life and human suffering caused by the war in Vietnam. He was protesting against our government’s deep military involvement in the war. He felt that all citizens must speak their convictions about our country’s action.”[5]

Within a couple of days, Anne received a handwritten letter, which Norman had apparently mailed on his way to the Pentagon. It read, in part[6]:

Dearest Anne:

Please don’t condemn me…. For weeks, even months, I have been praying only that I be shown what I must do. This morning with no warning I was shown, as clearly as I was shown that Friday night in August 1955, that you would be my wife…. At least I shall not plan to go without my child, as Abraham did. Know that I love thee but must act for the children in the Priest’s village.

Norman

With his letter, Norman had included a newspaper clipping about a Vietnamese village that had been decimated by U.S. bombers. On the day of his suicide, he and Anne had discussed the story as she prepared lunch in their kitchen. An avowed pacifist and Quaker, Norman was troubled by the news, as he had been about so many of the reports coming out of Vietnam.

Anne recalled their last meal together in a memoir published years later:

“‘What can we do that we haven’t done?’ he asked. His tone was grave, but he didn’t seem distraught or depressed. He appeared quite calm. I kept stirring the soup and responded, ‘I really don’t know.’ We had done everything I could imagine doing to try to stop the war: praying, protesting, lobbying, withholding war taxes, writing letters to newspapers and people in power. I remember adding, ‘All I know is that we mustn’t despair.’”[7]

After lunch, she headed out to run some errands. Norman, of course, headed to the Pentagon.

With his very public self-immolation, he adopted the method of protest that had been employed by Buddhist monks – notably Thích Quảng Đức – to protest repression by the South Vietnam government. North Vietnamese officials immediately celebrated Morrison as a martyr. The government issued a stamp with his picture on it, and Ho Chi Minh cabled Anne Morrison, inviting her to Vietnam.[8]

Back at home, Morrison's actions were fodder for debate. Impassioned opinions, such as those spelled out in letters to The Baltimore Sun, ran the gamut.

“Norman Morrison is a true hero in the highest sense. He did not give his life in killing others to “keep his country free,” he took his own life to keep his country from taking away the freedom of others.” – Irma W. Simon[9]

“To place the suicide of Mr. Morrison in the category of martyrdom would be a mistake; it belongs in one of the more macabre subdivisions of the science of abnormal psychology. In this country, innumerable forms of effective protest are available. When a citizen concludes that the only suitable method is to douse himself with kerosene and set himself afire, we have good reason to doubt his sanity.” –E. Ulrie Buddemeyer[10]

“The death of Norman Robert Morrison before the Pentagon last Tuesday was a not suicide, but murder. Our souls calloused over with indifference, acquiescent to violence, impervious to human suffering, murdered Norman Morrison. We murdered him just as coldly, just as mechanically, just as insensitively as daily we murder men, women and children in Vietnam.” –Dorothy Mock[11]

Defense Secretary Robert McNamara was shaken by the event, as he discussed in his autobiography in 1995. “I reacted to the horror of his action by bottling up my emotions, and avoided talking about them with anyone – even my family. I knew [they] shared many of Morrison's feelings about the war.”[12]

Following Norman’s suicide, his family struggled to return to some sort of normalcy, which was, of course, impossible even as the public memory of his immolation faded. Anne tried to set an example of strength for her three children – Emily had an older brother, Benjamin, and an older sister, Christina. “I told them their dad had died because children were suffering in a country far away and he died to help them and to stop the war that was causing them such pain and suffering.”[13]

All these years later, perhaps the most perplexing part of the story concerns baby Emily. Did Norman intend to sacrifice her life as part of his protest? Did he say as much in his letter to Anne with his reference to the Biblical story of Abraham? Did Norman count on Emily being spared at the last minute, as Abraham’s son Issac had been spared?

“At least I shall not plan to go without my child, as Abraham did.”

In the hectic events of November 2, 1965, witnesses were unclear about whether Norman had set Emily down before the flames could engulf her, or whether she was pulled from his arms by bystanders.

Emily offered her take to The Guardian in 2010:

“By involving me, I feel he was asking the question, ‘How would you feel if this child were burned too?’ People condemned him for my presence there when perhaps he wanted us to question this horrifying possibility. I believe I was there with him ultimately to be a symbol of truth and hope, treasure and horror altogether. And I am fine with my role in it.”[14]

Only Norman Morrison, himself, knows for sure.

Footnotes

- ^ Gold, William. “Man Dies as ‘Human Torch’ At Pentagon, Child Is Saved.” Evening Star. November 3, 1965, sec. A.

- ^ Flintoff, John-Paul. “I Told Them to Be Brave.” The Guardian, October 16, 2010. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2010/oct/16/norman-morrison-vietnam-war-protest.

- ^ Gold, William. “Man Dies as ‘Human Torch’ At Pentagon, Child Is Saved.” Evening Star. November 3, 1965, sec. A.

- ^ Sehlstedt, Albert. “Baltimore Quaker With Baby Sets Self Afire, Dies In War Protest AT Pentagon.” The Sun (1837-1992); Baltimore, Md. November 3, 1965.

- ^ Gold, William. “Man Dies as ‘Human Torch’ At Pentagon, Child Is Saved.” Evening Star. November 3, 1965, sec. A.

- ^ Welsh, Anne Morrison, and Joyce Hollyday. Held in the Light: Norman Morrison’s Sacrifice for Peace and His Family’s Journey of Healing. Maryknoll, N.Y: Orbis Books, 2008. P. 36.

- ^ Welsh, Anne Morrison, and Joyce Hollyday. Held in the Light: Norman Morrison’s Sacrifice for Peace and His Family’s Journey of Healing. Maryknoll, N.Y: Orbis Books, 2008. P. 36.

- ^ Hendrickson, Paul. “Daughter Of the Flames: In 1965, Norman Morrison Held His Baby Emily and Set Himself on Fire over the War in Vietnam. Today, the Family Remembers. Morrison Child of Fire.” The Washington Post (1974-Current File); Washington, D.C. December 2, 1985.

- ^ “Letters to the Editor.” The Sun (1837-1992); Baltimore, Md. November 5, 1965.

- ^ “Norman Morrison: Excerpts from Letters.” The Sun (1837-1992); Baltimore, Md. November 13, 1965.

- ^ “Norman Morrison: Excerpts from Letters.” The Sun (1837-1992); Baltimore, Md. November 13, 1965.

- ^ Flintoff, John-Paul. “I Told Them to Be Brave.” The Guardian, October 16, 2010. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2010/oct/16/norman-morrison-vietnam-war-protest.

- ^ Flintoff, John-Paul. “I Told Them to Be Brave.” The Guardian, October 16, 2010. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2010/oct/16/norman-morrison-vietnam-war-protest.

- ^ Flintoff, John-Paul. “I Told Them to Be Brave.” The Guardian, October 16, 2010. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2010/oct/16/norman-morrison-vietnam-war-protest.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)