The Hay-Adams Hotel's Perpetual Guest

On the corner of 16th and H Streets, NW, sits the Hay-Adams Hotel, an iconic Washington institution and a hub for the District’s elite. If ‘to see and be seen’ is a sport, then the Hay-Adams has been D.C.’s arena since its opening in 1928.[1] One of the few places in the Federal City “where nothing is overlooked but the White House,” according to the hotel’s motto, the Hay-Adams is in good company in Lafayette Square, with an enviable view of Lafayette Park, St. John’s Episcopal Church, the Washington Monument in the distance, and, of course, the executive mansion.

Inside the hotel, guests find an elegant and inviting interior, where generously lacquered woodwork lines the lobby walls and glistens under the glow of chandeliers overhead. Attentive employees in crisp uniforms flit beneath ornate ceilings and billowing tapestries as visitors lounge on plush couches and sturdy armchairs, waiting patiently to catch a glimpse of politicians or journalists entering the palatial hotel. Up through the grand hallways — always adorned by fresh flowers — are the Hay-Adams’ luxury accommodations, which appear to be steeped in opulence.[2] Light pouring in from balcony windows in each suite reveals a bounty of carefully selected amenities.

The atmosphere at the Hay-Adams Hotel remains one of hospitality and timelessness, just ask the woman who’s supposedly made it her home for over 130 years. Tarnishing its long-held reputation of extravagance and exclusivity is the hotel’s only unwanted guest: the esteemed ghost of the Hay-Adams, Marion Hooper Adams.

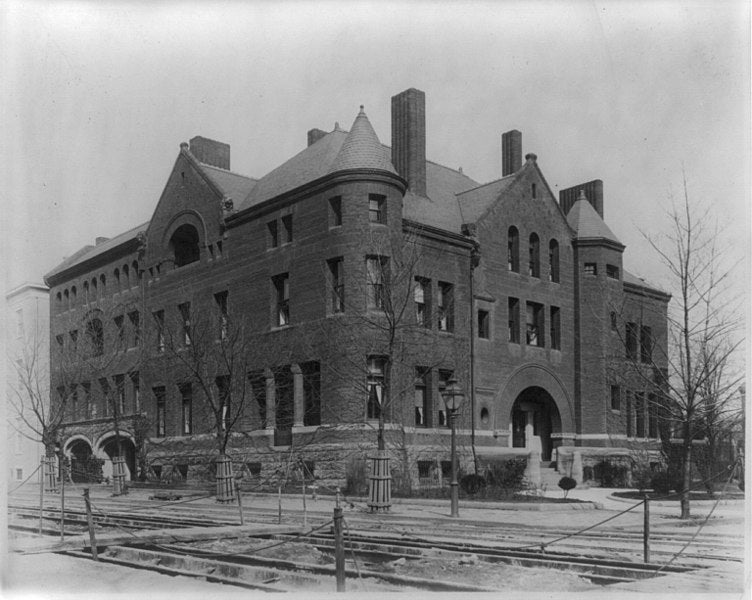

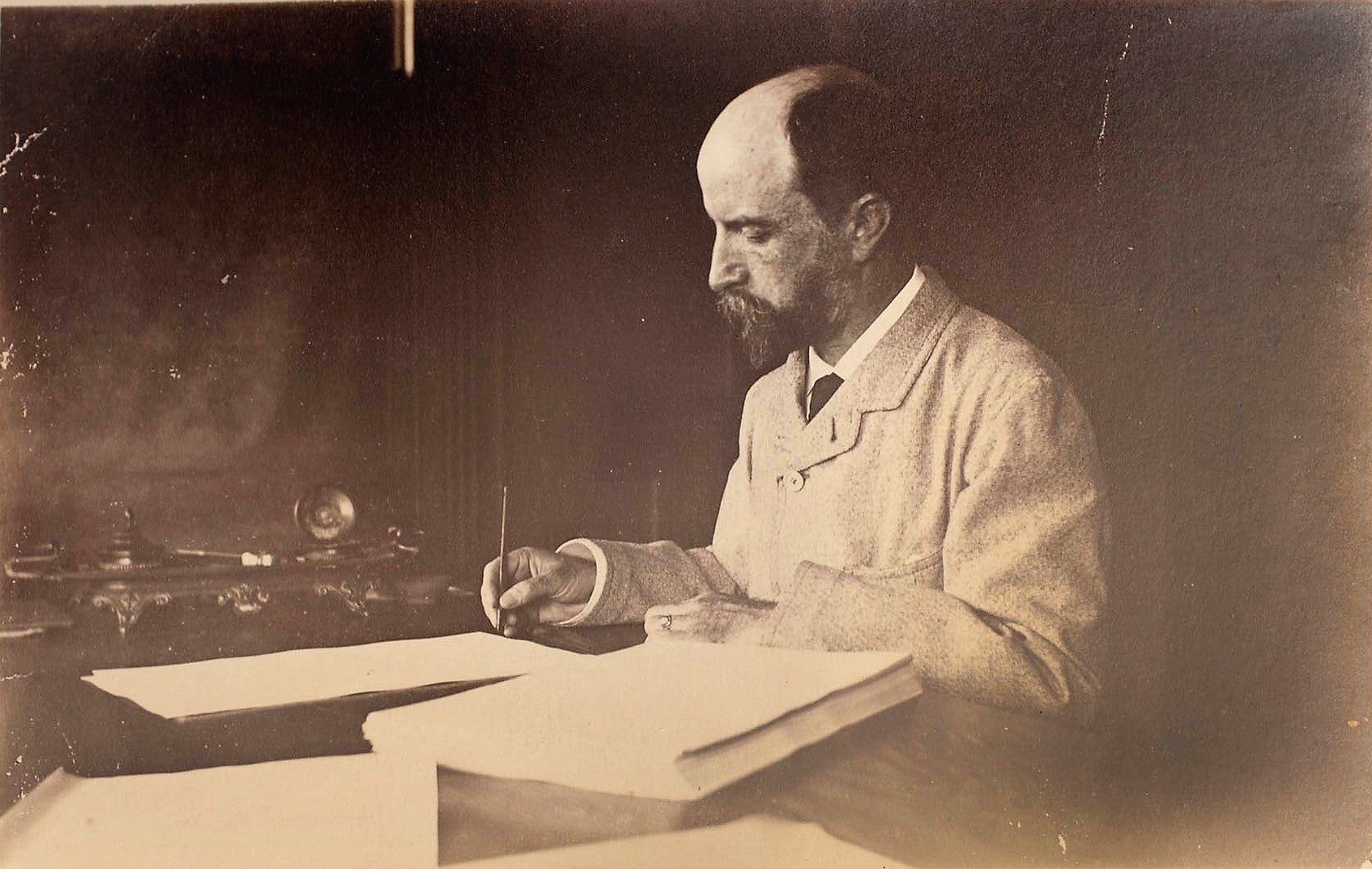

Mrs. Adams, who went by “Clover,” lived on the site of the Hay-Adams hotel in the mid-1880s.[3] Beginning in 1884, she and her husband, Henry Adams, a descendant of two presidents and distinguished author, shared a parcel of land with their closest friends: John Hay, a US Ambassador and Secretary of State, and his wife, Clara.[4] By that point, the Adamses spent seven successful and social years in Washington, having moved from Boston in 1877.[5] But, after garnering popularity in the capital, Henry decided that their home should reflect their accrued elite status.[6] So, they partnered with their friends, the Hays, to build an impressive joint-home.[7]

It was there, in the almost-finished Hay-Adams House, that Clover died on December 6, 1885,[8] of causes cloaked in mystery and tragedy.

For those who have encountered her spirit in the years since, Clover’s posthumous manifestations on the property help tell her story, as each spectral appearance serves as a testament to her life of brilliance and a reminder of her heartbreaking death.

On the fourth floor of the Hay-Adams Hotel, Clover has been reported to engage with hotel guests and employees alike as she so often did during her life as a socialite. [9]

She makes her presence known by opening previously-locked doors in unoccupied suites and the hum of radios flickering to life without provocation.[10][11][12] Housekeepers have reported that she remains as social as ever, whispering their names in empty rooms, asking “what do you want?” and even wrapping invisible arms wrap around them in a gentle embrace.[13][14][15][16]

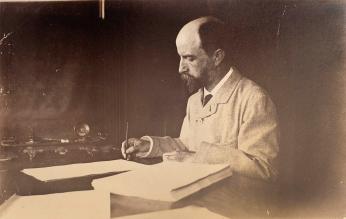

Hailing from a family of Boston Brahmins, Clover spent her youth and early adulthood in Massachusetts.[17] In 1872, at the age of 30, she married Henry Adams, also from a prominent Boston family.[18] As both Mr. and Mrs. Adams were perfectionists, strong-willed, and brilliant[19] — Henry has been called the American Voltaire and Clover was dubbed “a perfect Voltaire in petticoats” by novelist Henry James[20] — their marriage was complicated by a sometimes toxic commitment to self-betterment. This is evident in some of Henry’s comments which suggest he thought of Clover as unrefined. While they were engaged, Henry wrote to a friend, “We shall improve her,” according to a 1936 Washington Post review of Clover’s then-recently-published collection of letters.[21] Later in their marriage, Henry reportedly said that his wife “has a very active and quick mind and has run over many things, but she really knows nothing well.”[22]

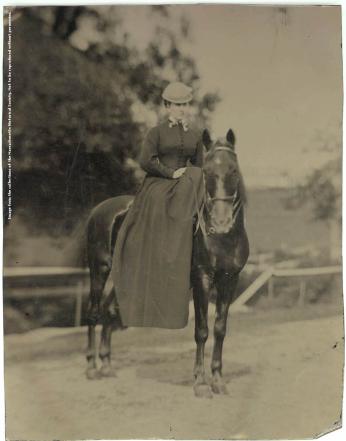

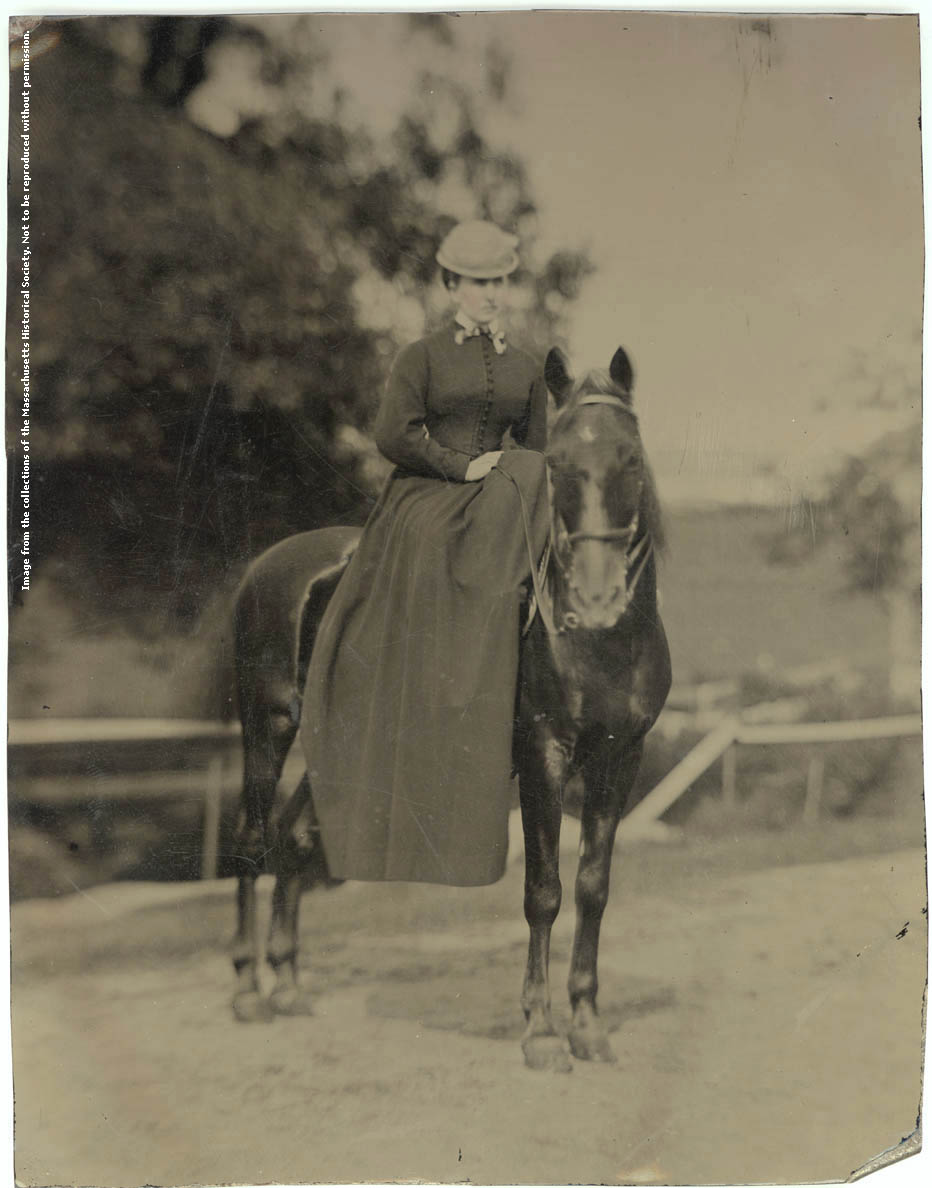

Still, Henry confessed that he was “absurdly in love” with Clover, and rightly so for all the accomplishments of the Renaissance woman.[23] Known, above all, for her wit, Clover was beautiful, athletic, fluent in French and Greek, an avid reader of classic literature, an equestrian, and a lover of art.[24] Early in their marriage, while Henry taught history at Harvard, Clover discovered that her greatest strength was her charm, as she easily established an unrivaled social salon in Boston’s Back Bay.[25] Upon their move to Washington, the popularity of her salon continued, with the Adamses’ home becoming a center for the intellectual, artistic, and political elite of the era.[26]

While Clover’s world was broadened as Henry had hoped, it seems Henry's intentions of improving his wife might have been too successful for his liking. Ever the perfect hostess, Clover could captivate five or six men in conversation at a single dinner party, which she would often hold in her husband’s absence, much to the delight of D.C.’s gossips.[27] Unfortunately, Clover’s apparent magnetism strained her marriage.

The Washington Post explained that “there are indications that Henry was extremely possessive and resented a little this excessive popularity. When on one occasion she fled for a short visit to friends in New York, Henry met her at the station upon her return and announced that he was glad she had enjoyed her week but that ‘it’s his last alone.’”[28] Whether overbearing or an extension of his devotion, this reaction suggests Henry might have regretted introducing Clover to the social arena outside of Boston.

Some accounts suggest Clover became “snobbish” under Henry’s tutelage, supposedly adopting a severity and criticality that she had not had in her youth.[29] Clover’s transformation, for better or for worse, is captured by the letters she wrote to her father, Robert W. Hooper, for almost fifteen years. Their correspondence began just after her marriage to Henry and documented Clover’s metamorphosis from Boston socialite to the social arbiter of Washington. Even the switch of her signature from “Lovingly, Clover” to the formal “Marian Adams” conveys her early adoption of propriety.[30] However, the fact that she never failed to write her father suggests that, at her core, Clover never abandoned her roots.

Clover was only five years old when she lost her mother, at which point Robert became the 19th-century equivalent of a stay-at-home-father and completely overtook the education and care of his three daughters.[31] Her father must have served as a confidante since childhood, as, throughout her marriage, Clover shared everything with him. In her weekly letters, she detailed every dinner party, every new acquaintance, every social outing, and every new endeavor.[32] In one 1883 installment of her correspondence, Clover wrote about the first attempt at the art for which she would be most celebrated: “Am going to take a photo with my new machine.”[33]

At the age of 39, Clover Adams picked up a camera for the first time and demonstrated her boundless versatility.[34] Teaching herself the principles of photography, Clover wrote in September of 1883, “I’ve gone in for photography and find it very absorbing.”[35] Clover mainly focused her talents on landscape and portrait photography when exploring her new hobby, creating a collection of photographs that exhibit her keen eye and knack for composition. But it is her self-portrait that is most revealing. In choosing to keep her face completely hidden under a large hat, Clover’s portrait potentially suggests a struggle with self-acceptance. Clover, through the years, became vulnerable as her identity was challenged by her husband’s expectation of exceptionalism.[36]

While she was never entirely Henry’s or society’s puppet, all went south for Clover Adams when her father died on April 13, 1885.[37] Clover, unable to lean on her only respite from the pressures of living in the public eye, sunk into a depression so profound that she was rendered an "invalid."[38]

Clover found an escape through her photography; unfortunately, it was not in capturing photographs. As winter settled on Washington, so too did sorrow and solitude settle on Clover Adams. An old friend came calling on the morning of December 6, 1885.[39] When Henry went to her quarters to see if she was willing to receive company, he found his wife unconscious and prostrate on her bedroom floor.[40] Henry ran frantically to collect Dr. C. E. Hagner, who lived two blocks down on H Street, and when the pair returned, they found Clover dead.[41]

Local newspapers, including the Washington Post and Evening Star, reported that her death was the result of “paralysis of the heart.”[42][43] Clover was supposedly no more than a victim of “Death’s sudden summons,” as far as the public would immediately understand.[44] Considering she was such a prominent figure in Washington, it was important to protect her reputation. But on that December morning, deep in the unfinished Hay-Adams House, Clover died by suicide by drinking potassium cyanide, a chemical she used to develop her photographs.[45]

Henry, although typically austere, was destroyed by Clover’s death. He wrote to one of his wife’s close friends in the year following her death, “The only moments of the past that I regret are those when I was not actively happy…My only wonder is whether I could have managed to get more out of the twelve years than we got; and if we really succeeded in being as happy as was possible, I have nothing more to say.”[46] And later, after the death of his father shortly after Clover, “During the last eighteen months I have not had the good luck to attend my own funeral, but with that exception I have buried pretty nearly everything I lived for.”[47]

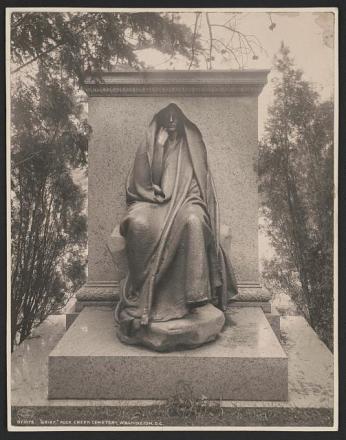

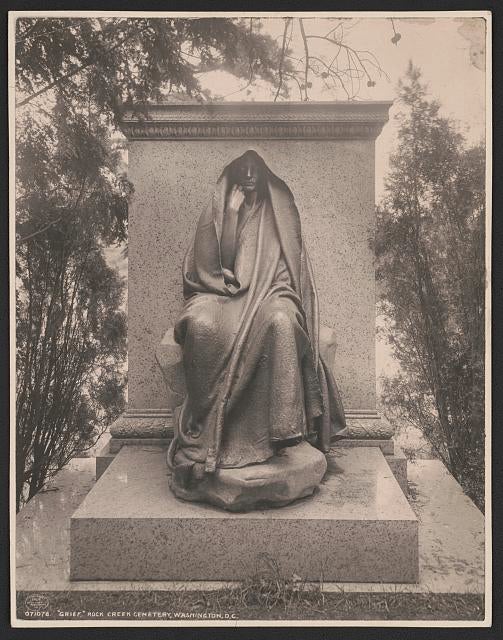

Curiously, Henry Adams completely omitted Clover from his autobiography, The Education of Henry Adams.[48] His silence was notorious, especially since he went so far as to burn all of Clover’s correspondence, including the letters she received from her father, and refused to discuss her after her death.[49] Despite this reclusiveness, Henry did commission a statue to honor his wife.[50] Appropriately entitled “Grief,” the Augustus Saint-Gaudens sculpture features a cloaked bronze figure to mark Clover’s otherwise anonymous grave in Rock Creek Cemetery.[51] While the memorial does not depict Clover’s likeness, the anonymous figure represents, per Henry’s request, the depth of sadness conjured by his wife’s death and the abstract cycle of life and death.[52] Henry was buried with his wife upon his death on March 27, 1918.[53]

It seems that Clover, perhaps anchored by her husband’s grief or her refusal to be erased, has a hand in her remembrance. Every December, around the anniversary of her death, the fourth floor of the Hay-Adams Hotel reeks of Clover’s memory ... literally. Guests report catching the scent of bitter almonds — or the smell of potassium cyanide — wafting through the hotel’s halls.[54] Her distant sobs echo in empty rooms,[55] a reminder of the woman who will likely never check out of the Hay-Adams Hotel.

Footnotes

- ^ https://www.hayadams.com/our-hotel/history

- ^ Joe Ruggiero. YouTube. July 01, 2015. Accessed October 29, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HYYjrrAz44Y.

- ^ Natalie Dykstra, Clover Adams: a Gilded and Heartbreaking Life, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012), 167.

- ^ Donna Evers, “Two Families, One Roof,” Washington Life Magazine, Summer 2006, https://www.washingtonlife.com/issues/summer-2006/historical_landscapes/.

- ^ Natalie Dykstra, Clover Adams: a Gilded and Heartbreaking Life, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012), 80.

- ^ Donna Evers, “Two Families, One Roof,” Washington Life Magazine, Summer 2006, https://www.washingtonlife.com/issues/summer-2006/historical_landscapes… Hay-Adams House was designed by Henry Hobson Richardson, a Harvard classmate of Mr. Adams. Hays and Adams requested that Richardson create two independent homes that would be attached and “share the same facade.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Death’s Sudden Summons: Mrs. Henry Adams Stricken by Heart Disease,” The Washington Post, December 7, 1885, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ Misty Witenberg, “Haunted Hotels in Washington, DC,” USA Today, March 15, 2018, https://traveltips.usatoday.com/haunted-hotels-washington-dc-24181.html.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ https://www.historichotels.org/press/the-eerie-archive-great-american-g…

- ^ Lara Grant, “The 13 Most Haunted hotels in the World,” York Daily Record, October 21, 2015, https://www.ydr.com/story/life/2015/10/21/13-most-haunted-hotels-world/….

- ^ Linea Covington, “7 Haunted Hotels Around the World,” Forbes Travel Guide, October 12, 2018, https://stories.forbestravelguide.com/7-haunted-hotels-around-the-world.

- ^ Misty Witenberg, “Haunted Hotels in Washington, DC,” USA Today, March 15, 2018, https://traveltips.usatoday.com/haunted-hotels-washington-dc-24181.html.

- ^ https://www.historichotels.org/press/the-eerie-archive-great-american-g…

- ^ Lara Grant, “The 13 Most Haunted hotels in the World,” York Daily Record, October 21, 2015, https://www.ydr.com/story/life/2015/10/21/13-most-haunted-hotels-world/….

- ^ Natalie Dykstra, Clover Adams: a Gilded and Heartbreaking Life, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012), 3-11.

- ^ Agnes E. Meyer, “The Education of Mrs. Henry Adams: Letters of ‘Clover’ Adams to Her Father Reveal Charm and Wit.,” The Washington Post, December 9, 1936, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Natalie Dykstra, Clover Adams: a Gilded and Heartbreaking Life, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012), xiii.

- ^ Agnes E. Meyer, “The Education of Mrs. Henry Adams: Letters of ‘Clover’ Adams to Her Father Reveal Charm and Wit.,” The Washington Post, December 9, 1936, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Natalie Dykstra, “Marion Adams: American Socialite and Photographer,” Encyclopedia Britannica, September 9, 2018, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Marian-Adams.

- ^ Natalie Dykstra, Clover Adams: a Gilded and Heartbreaking Life, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012), 73-77.

- ^ Natalie Dykstra, Clover Adams: a Gilded and Heartbreaking Life, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012), 84-94.

- ^ Agnes E. Meyer, “The Education of Mrs. Henry Adams: Letters of ‘Clover’ Adams to Her Father Reveal Charm and Wit.,” The Washington Post, December 9, 1936, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Natalie Dykstra, Clover Adams: a Gilded and Heartbreaking Life, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012), 17.

- ^ https://www.masshist.org/features/clover-adams/selected-letters

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Who was Marian “Clover” Hooper Adams?,” Massachusetts Historical Society, http://www.masshist.org/features/clover-adams.

- ^ https://www.masshist.org/features/clover-adams/approach-to-photography

- ^ Agnes E. Meyer, “The Education of Mrs. Henry Adams: Letters of ‘Clover’ Adams to Her Father Reveal Charm and Wit.,” The Washington Post, December 9, 1936, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ “Who was Marian “Clover” Hooper Adams?,” Massachusetts Historical Society, http://www.masshist.org/features/clover-adams.

- ^ “Death’s Sudden Summons: Mrs. Henry Adams Stricken by Heart Disease,” The Washington Post, December 7, 1885, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Sudden Death of Mrs. Henry Adams,” The Evening Star, December, 7, 1885, DC Public Library: Evening Star.

- ^ “Death’s Sudden Summons: Mrs. Henry Adams Stricken by Heart Disease,” The Washington Post, December 7, 1885, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ Natalie Dykstra, Clover Adams: a Gilded and Heartbreaking Life, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012), xvi.

- ^ https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=2274&img_step=1&br…

- ^ https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=2275&img_step=1&br…

- ^ Agnes E. Meyer, “The Education of Mrs. Henry Adams: Letters of ‘Clover’ Adams to Her Father Reveal Charm and Wit.,” The Washington Post, December 9, 1936, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ Brian Clark, “Clover Adams’ Memorial: From a Husband Who Would No Longer Speak Her Name,” Atlas Obscura, July 23, 2013, https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/adams-memorial-rock-creek-cemeter….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Natalie Dykstra, Clover Adams: a Gilded and Heartbreaking Life, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012), 227.

- ^ Ruth Steinhardt, “The Nation’s Haunted Capital,” GW Today, October 25, 2017, https://gwtoday.gwu.edu/nations-haunted-capital#hayadams.

- ^ Misty Witenberg, “Haunted Hotels in Washington, DC,” USA Today, March 15, 2018, https://traveltips.usatoday.com/haunted-hotels-washington-dc-24181.html.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)