How Les Misérables Became Lee's Miserables

When Victor Hugo’s novel Les Misérables was first published in the spring of 1862, it was panned by critics. But critical analysis and popularity with consumers don’t always go hand-in-hand.

Readers couldn’t get enough of the novel. Hugo’s epic story about Jean Valjean was translated into various languages and spread across the globe. Within a few months, American audiences were devouring a five-volume serialized version, translated by renowned classicist Charles E. Wilbour.[1] The volumes, which were printed on colorful broadsides, could be had for a nickel or dime, and sales ran into the hundreds of thousands.[2] Union soldiers gobbled them up and carried them to battle.

Wilky James (44th and 54th Massachusetts) was one such soldier, writing in 1863, “Today is Sunday and I’ve been reading Hugo’s account of Waterloo in ‘Les Miserables’ and preparing my mind for something of the same sort. God grant the battle may do as much harm to the Rebels as Waterloo did to the French.”[3]

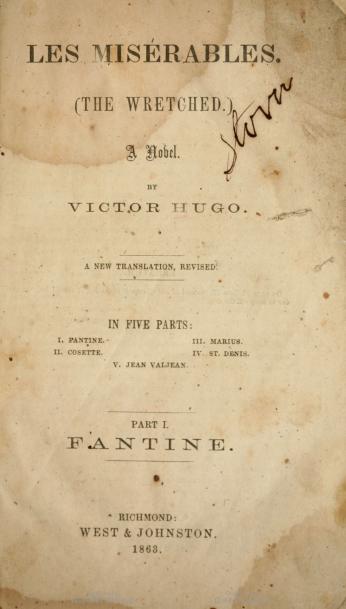

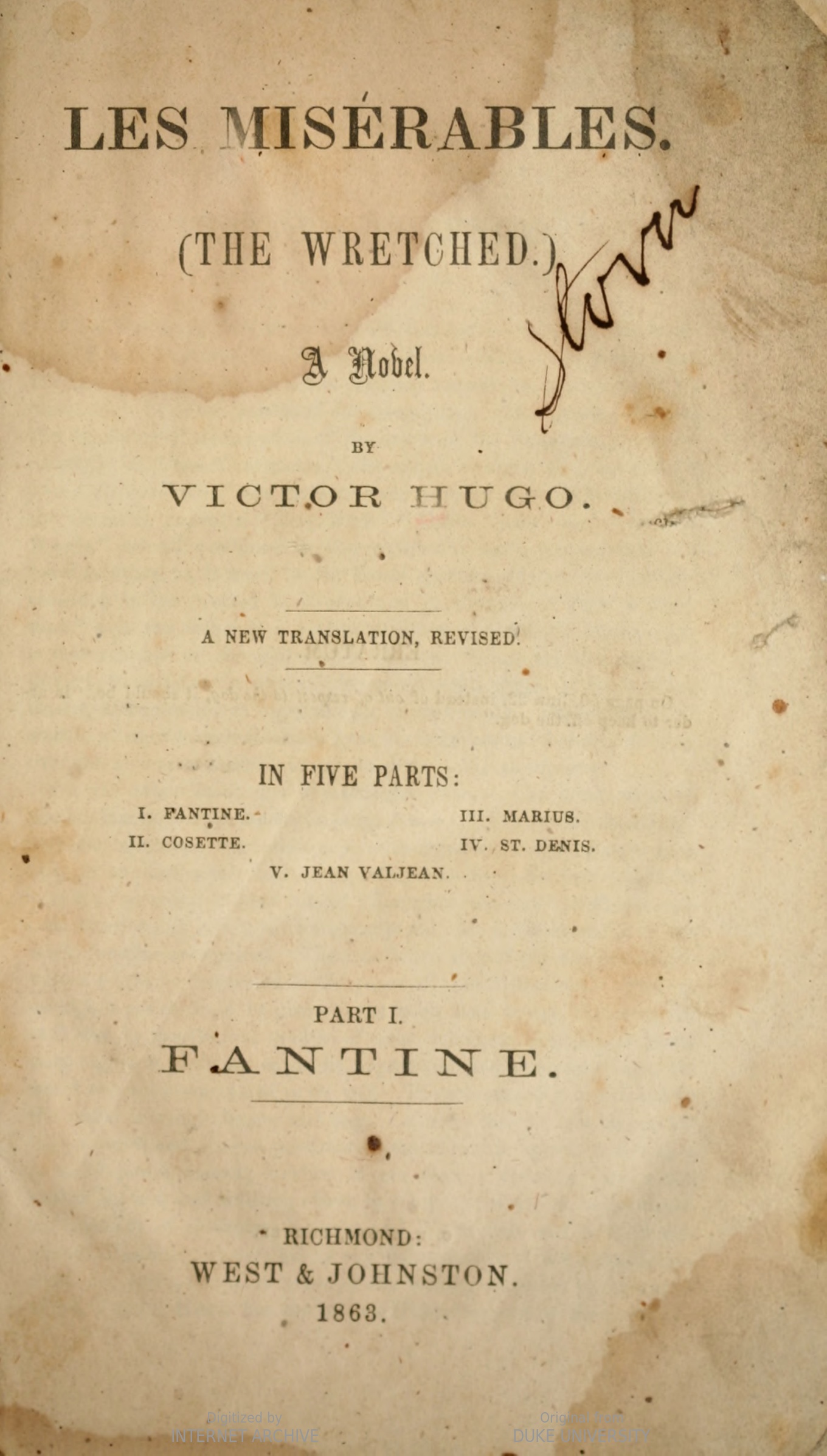

As popular as the book was in the north, it’s possible that it was even more popular in the Confederacy. Richmond, Virginia publisher West & Johnston soon began circulating their own edition based on a pirated version of Wilbour’s translation. (In the midst of the Civil War, Union copyright laws were ignored.) West & Johnston produced a soldier’s edition, which was distributed to Confederate army units on “sheep’s wool paper.”[4] As Confederate Army aide John Esten Cooke recalled later in his memoirs, the men couldn’t get enough of it.

Victor Hugo’s work, Les Misérables, had been translated and published by a house in Richmond; the soldiers, in the great dearth of reading matter, had seized upon it; and thus, by a strange chance the tragic story of the great French writer, had become known to the soldiers in the trenches. Everywhere, you might see the gaunt figures in their tattered jackets bending over the dingy pamphlets—“Fantine,” “Cosette,” or “Marius,” or “St. Denis,”—and the woes of “Jean Valjean,” the old galley-slave, found an echo in the hearts of these brave soldiers, immured in the trenches and fettered by duty to their muskets or their cannon.[5]

So, as the Civil War divided the country, Northerners and Southerners were united around a love for Les Misérables. For soldiers in the trenches on both sides, it offered an escape. But here’s the thing: Southerners weren’t reading the same book that had taken the world by storm. The West & Johnston version distributed to Confederate soldiers had been carefully edited.

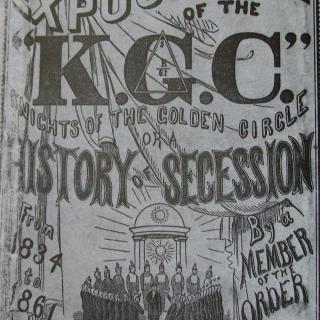

That’s because in its original form, Les Misérables – and Victor Hugo in general – presented a problem for the Confederacy. Hugo was an outspoken opponent of slavery and a vocal supporter of American abolitionist John Brown, who led the 1859 slave insurrection at Harpers Ferry. In fact some scholars have suggested that Brown was an inspiration for the character of Jean Valjean.

As Hugo lamented to the London News on December 2, 1859: “Assuredly, if insurrection is ever a sacred duty, it must be when it is directed against Slavery. John Brown endeavored to commence the work of emancipation by the liberation of slaves in Virginia. Pious, austere, animated with the old Puritan spirit, inspired by the spirit of the Gospel, he sounded to these men, these oppressed brothers, the rallying cry of Freedom.”[6]

And so, when West & Johnston published their version in 1863, certain aspects of Hugo’s masterwork – particularly those illustrating his abolitionist sympathies – were changed or eliminated. In the preface to the Confederate version, a writer identified only as “A.F.” attempted to explain away the changes as insignificant to the overall story.

It is proper to state here, that whilst every chapter and paragraph in any way connected with the story has been scrupulously preserved, several long, and it must be confessed, rather rambling disquisitions on political and other matters of a purely local character, of no interest whatever on this side of the Atlantic, and exclusively intended for the French readers of the book, have not been included in this reprint. A few scattered sentences reflecting on slavery — which the author, with strange inconsistency, has thought fit to introduce into a work written mainly to denounce the European systems of labor as gigantic instruments of tyranny and oppression — it has also been deemed advisable to strike out. With those exceptions — and they are after all but few and unimportant — the original work is here given entire. The extraneous matter emitted has not the remotest connection with the characters or the incidents of the novel, and the absence of a few anti-slavery paragraphs will hardly be complained of by Southern readers.[7]

So, what did the censorship look like in practice? Here’s one example:

Wilbour translation: “I voted for the downfall of the tyrant; that is to say, for the abolition of prostitution for woman, of slavery for man, of night for the child.”

West & Johnson version: “I voted for the annihilation of the tyrant; that is to say, for the abolition of prostitution for woman, of degeneracy for man, and of night for the child.”[8]

This is just the tip of the iceberg. For a more detailed exploration of the differences between the Wilbour translation and the West & Johnston version, check out this presentation by Jessica Christy (a.k.a. Hernaniste) for the 2013 Nineteenth Century French Studies Colloquium in Richmond, Virginia.

There were clearly political motivations for censoring Les Misérables and the edits may have made the novel more palatable for Southern readers. However, the book's immense popularity on the battlefield was likely due to something else.

Experiencing day-to-day miseries while fighting what would prove to be an unwinnable war, these soldiers came to identify with the book so much that they began to see themselves in it. As John Esten Cooke recalled:

That history of “The Wretched,” was the pabulum of the South in 1864; and as the French title had been retained on the backs of the pamphlets, the soldiers, little familiar with the Gallic pronunciation, called the book “Lees Miserables!” Then another step was taken. It was no longer the book, but themselves whom they referred to by that name. The old veterans of the army thenceforth laughed at their miseries, and dubbed themselves grimly “Lee’s Miserables!”[9]

It didn’t take much ingenuity to convert the French pronoun “Les” into a reference to Confederate general Robert E. Lee. However, this was more than just a play on words. Southern soldiers were effectively expanding the definition of the oppressed and, in doing so, tying themselves back to one of the main themes of Hugo’s novel: the struggle of the downtrodden.

Would the author have been pleased at this appropriation of his work? Well, that’s complicated.

As scholar David Bellos notes, “This ‘localization’ of Hugo’s novel to the views and sensitivities of slave-owning states is a travesty to that author’s position and of some of the meanings of his work.”[10]

Then again, Bellos observes, “Hugo’s novel explicitly overrides the distinction between the destitute, the despicable and the hapless, merging them into a single collective that reconfigures the language of nineteenth century France. ‘There is a point where the poor and the wicked become mixed up and lumped together in one fateful word: les misérables’ [p. 671, adapted]. Why should ragged soldiers by excluded from this new community of the downtrodden?”[11]

However you want to interpret this history, one thing seems certain: Civil War battlefields were full of Les Misérables.

Footnotes

- ^ Bellos, David. The Novel of the Century: The Extraordinary Adventure of Les Misérables. New York: Farrar, Strous and Giroux, 2017: 239. The first volume, Fantine: A Novel, appeared in New York by June and was followed by Cosette in July, Marius and Saint-Denis in November and Jean Valjean in December.

- ^ Bellos, 239.

- ^ Masur, Louis P. “In Camp, Reading ‘Les Misérables.’” Opinionator (blog), February 9, 2013. https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/02/09/in-camp-reading-les-miserables/.

- ^ Stiles, Robert. Four Years Under Marse Robert. https://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/stiles/stiles.html.

- ^ Cooke, John Esten. Mohun, Or, The Last Days of Lee and His Paladins: Final Memoirs of a Staff Officer Serving in Virginia, 1869. Gutenberg.org.

- ^ Hugo, Victor. “Letter to the London News Regarding John Brown,” December 2, 1859. Wikisource.

- ^ Hugo, Victor. Les Misérables (The Wretched): A New Translation, Revised. Richmond: West & Johnston, 1863: iv.

- ^ Bellos, 240.

- ^ Cooke, John Esten. Mohun, Or, The Last Days of Lee and His Paladins: Final Memoirs of a Staff Officer Serving in Virginia, 1869. Gutenberg.org.

- ^ Bellos, 240.

- ^ Bellos, 241.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)