“This is Serious, These Guys Will Kill You”: Salvatore Cottone and the True Story of the Short-Lived D.C. Mafia

New York had ‘Lucky’ Luciano, Chicago had Al Capone, and Washington D.C., had… Salvatore Cottone? When you think of Washington D.C., you probably don’t think about the mafia. And for good reason. “Who would be so stupid as to go into the backyard of the FBI, CIA, other law enforcement” to set up a criminal enterprise, asks former assistant U.S Attorney Michael Smythers, who helped prosecute D.C.’s most famous mafia case almost thirty years ago. But, he concedes, “it was wide open.” [1] The arrival of Salvatore Cottone and his brothers in the 1970s changed all that. When Cottone departed in 1990, it was for the federal penitentiary, and he left behind a legacy of drug-dealing, arson, and attempted murder.

Salvatore Cottone was born in Sicily in 1947 and arrived in the United States just shy of his twentieth birthday. He started working as a dishwasher at a restaurant in New Jersey.[2] If you asked him, that was where his “American Dream” started: working his way up in the restaurant industry, climbing the ladder from immigrant to owner in his adopted nation. If you asked the FBI, that was where he rubbed elbows with the Gambinos and other mafia heavyweights, cutting his teeth in the world of organized crime.[3]

When Cottone came to the D.C. area with his two brothers in the mid-1970s, he opened a couple of pizza shops, including a Pizza Delight on 14th Street NW. These were no normal pizza shops, however. They were what you might call “full-service establishments”, which is to say, you could buy a lot more than a slice of pepperoni behind the counter — if you knew who to ask. Cocaine, heroin, you name it — they carried it at Cottone’s pizzerias. And though the business wasn’t exactly family-friendly, it was at least family-run: Cottone put his younger brother Giuseppe, a “flashy, ambitious young man who liked fast motorcycles and ritzy cars” in charge of the narcotics distribution.[4]

But even with the added income from drug sales, the restaurant business in D.C. can be unforgiving. Cottone and his associates had to compete with well-known D.C. eateries, long established restaurants with reliable clientele. So, in 1978, Cottone sought to gain an advantage over one particular competitor, a neighborhood landmark he believed was drawing business away from one of his cafes. His method of beating the competition? He had it burned it to the ground. [5]

Bassin’s Café on Pennsylvania Avenue was a historic locale billed as D.C.’s first sidewalk café. It was popular with local bureaucrats – in Cottone’s eyes, too popular. Cottone sent his henchman Alfredo “The Butcher” Toriello to set the place alight. Toriello was “perfectly cast for the role of mafia muscle…built like an overweight grizzly bear,” wrote one reporter; “a brawny, ham-handed guy packed like a sausage into a white T-shirt and black pants,” wrote another.[6] Torriello and an associate entered the eatery in the early hours of the morning on Tuesday, October 17. They set to work emptying several five-gallon Coca-Cola drums filled with gasoline onto the carpet. But before they could finish, Toriello heard a noise in the café and got skittish. He used Bassin’s phone to call Cottone and convince him to call it off: “I tell him I have a problem, there’s people inside,” Toriello recalled. Cottone, however, was unsympathetic: ‘“He tell me, ‘I don’t give a ****.”’[7] At 3:47 am, Bassin’s went up in flames.

By the time firefighters got the blaze under control two hours later, the once bustling café was a “charred hulk.”[8] Arson was immediately suspected, as fire officials were literally wringing gasoline out of the carpets. It was, in the words of one firefighter, “overkill.”[9] “We had the fire guy testify that there was so much gas [from the gasoline] that the gas pushed a lot of oxygen out and when it did go up, it blew up,” says Mike Smythers, “it blew the doors out.”[10]

A few years after the torching of Bassin’s, Cottone moved to Virginia Beach. It’s not entirely clear why he transplanted his base of operations, though Smythers thinks Cottone knew the feds were onto him. But if Cottone was spooked, he didn’t act like it. He continued to expand his restaurant holdings, moving into Fairfax and Norfolk, opening more Pizza Delights, cafes called Little Italys and even a wine importing business, the Hampton Roads Beverage Company. By the mid-1980s, Cottone had opened his flagship location, Michaelangelo’s Italian Restaurant, on Granby Street in Norfolk. Michaelangelo’s was a high-end establishment, and Cottone was like its mayor: he was “a fixture there, greeting customers by name and doling out free bottles of wine.”[11] Even here, however, criminal activity greased the wheels of his legitimate enterprises: Cottone had obtained the controlling interest in Michaelangelo’s by threatening bodily harm against co-owner Michael Zara’s children.[12]

Meanwhile, Cottone and his brothers continued to reap the profits of the lucrative drug trade, now operating out of both D.C. and Northern Virginia. The cocaine was imported by the members of Medellin Cartel, with the help of a secretary at the Colombian embassy on Massachusetts Ave. Once the cocaine entered the country, it was transported into the pizzerias, sometimes disguised as dog food, other times as groceries.[13] There was no shortage of demand for cocaine in the D.C. area in the 1980s — or pizza, for that matter — so it came as no surprise that business was booming.

Unfortunately for younger brother Giuseppe, one of his biggest clients was the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Giuseppe and an associate sold over $400,000 worth of cocaine to an undercover FBI agent in 1986 and 1987, the result of an eight-month long undercover sting led by tenacious special agent James Glass Jr. Glass, who had started investigating the Cottones in 1984, had used mafioso-turned-informant Lanfranco “Frank” Casali to introduce an undercover FBI agent to Giuseppe. Using evidence from the agent, along with wiretaps of Cottone-affiliated restaurants — the K-Street Eatery and Alfredo and Miriam’s pizzeria on Vermont Ave — the FBI indicted over two dozen men, including Giuseppe Cottone, Alfredo Toriello, a hardened mafioso named Beniamino Centurino, and their Medellin associates.[14] Giuseppe Cottone plead guilty on February 24, 1987. At his sentencing hearing, his brother Salvatore, who had avoided indictment in the case, was approached by Glass. “You’ll be next,” Glass told him.[15] Cottone spit on the floor in disgust.[16]

Special Agent Glass was FBI born and bred, his father having worked for the bureau decades before, and he was a veteran of organized crime cases stretching from Los Angeles to New Orleans.[17] By his own admission, he wasn’t your typical FBI agent: “I wore a leather jacket and drove a Porsche,” Glass says. “He’d get in that damn FBI car and just race it down the street… he was a loose cannon,” recalls Smythers with a chuckle. But in the world of organized crime, he was feared: Glass was “a bloodhound”, says Smythers, and he was hot on Cottone’s scent: “He told me he was gonna put him in jail within three years.”[18]

Glass’s promise to Cottone at his brother’s sentencing turned out to be the beginning of a complicated relationship between Cottone and the FBI. Aware of the fact that he was under investigation, and attempting to help his brother receive leniency from the federal government, Cottone repeatedly approached Glass and offered the Bureau information on the D.C.-area gun and drug trade. Recalling their meetings over thirty years later, two things stick out to Glass: “He was cocky,” says Glass, “and he always had nice shoes.” And as for the information he provided? “Most of it, we’d have no way to verify, he’s talking so far back.”[19] “They had mutual respect for each other,” says Smythers, “Glass knew how to play this guy, he never disrespected him… Cottone thought he would outsmart him.”[20] In the end, rather than work in his favor, the information only brought further suspicion upon Cottone: Glass was “surprised” that “someone who claimed to be so innocent had so much access to criminal information.”[21]

In truth, Cottone had no intent of leaving his life of crime, a fact of which Glass was well aware. And now, it was personal: Cottone sought revenge for the downfall of his brother, and zeroed in on Frank Casali as the chief target of his animus. Cottone held the former wise-guy personally responsible for his brother’s downfall. Glass worked with Alfredo Toriello, who had flipped on his boss, to concoct an elaborate scheme. Toriello would approach Cottone with the location of Casali, allegedly gleaned from a disgruntled FBI employee, and arrange a meeting between Cottone and the agent. But Cottone was suspicious and didn’t take the bait. Glass suggests Toriello wasn’t “smooth” enough to pull off the con.[22] Smythers is more blunt: “He was kind of a big dummy.”[23]

Glass went back to the drawing board, and this time he went for the long con. In February of 1988, Glass sent the Yugoslavian-born Sicilian-speaking Vincenzo “Vinnie” Hakanjin to earn Cottone’s trust. Hakanjin was a veteran informant, and over the course of ten months masquerading as a meat wholesaler from Pennsylvania, he succeeded. Cottone confessed his abiding hatred of Casali and recounted violent revenge fantasies: according to Hakanjin, Cottone “wanted to kill Frank and cut off one of his arms and send it to the FBI headquarters in D.C.”[24] Cottone wanted the pleasure of dealing with Casali himself, “so he could say a few words to him before killing him,” but when it became clear that would be impossible, he contracted out to his new friend Hakanjin to do the job. The price for Casali's life? $5,000. Cottone even told his hired gun how he wanted the deed carried out, testified Hakanjin: “He said he would prefer more of a Sicilian execution” — a single shot to the chest with a sawed-off shotgun.[25]

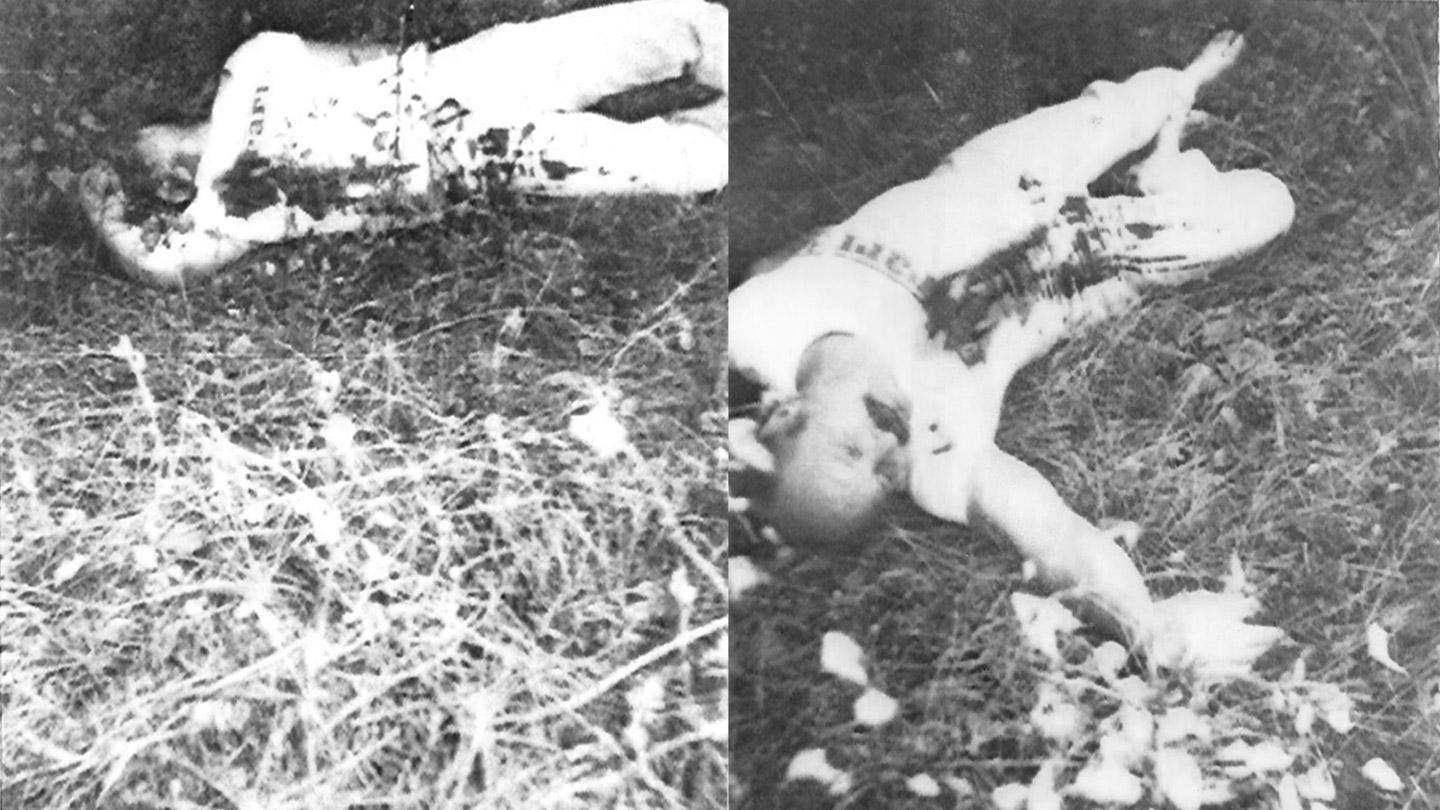

To Cottone’s delight, Hakanjin appeared to have succeeded. He approached Cottone after the supposed hit, bearing photographic evidence of Casali’s untimely demise. One courtroom reporter recreated the dramatic scene:

Inside Michaelangelo’s restaurant on Granby street, Vincenzo “Vinnie” Hakanjin offered proof to Salvatore Cottone that he had killed the man who squealed on Cottone’s younger brother, Giuseppe. Two Polaroid snapshots showed FBI informant Lanfranco Casali’s body sprawled in a ditch, his chest blown open by a shotgun blast, a toe missing off of his foot…The two men spoke Sicilian in low tones as the theme from “the Godfather” played in the background. They made their way to the kitchen where Sal Cottone turned on a gas burner, igniting the two photographs and said, “God Bless America.”[26]

The FBI agents listening in were floored, both by the success of their ploy and by the soundtrack that could be heard through the wire. “God, you just can't believe the feeling of hearing that title song from the movie the Godfather,” says Glass, “everybody's going, ‘Are you shitting me? Listen to what he's playing!’”[27]

Hakanjin even provided Casali’s “heavy gold medallion…with a diamond-studded seven in the middle.” It was a dream come true for Cottone. The only problem? Casali was alive and well. Casali had covered himself with ketchup and taken the photos, and had volunteered his jewelry for the sake of the con. Casali’s toe had been missing for years, the product of a hunting accident.[28] Glass had taken care of every detail, including sending FBI agents to question Cottone days after the supposed assassination. Cottone suspected nothing.

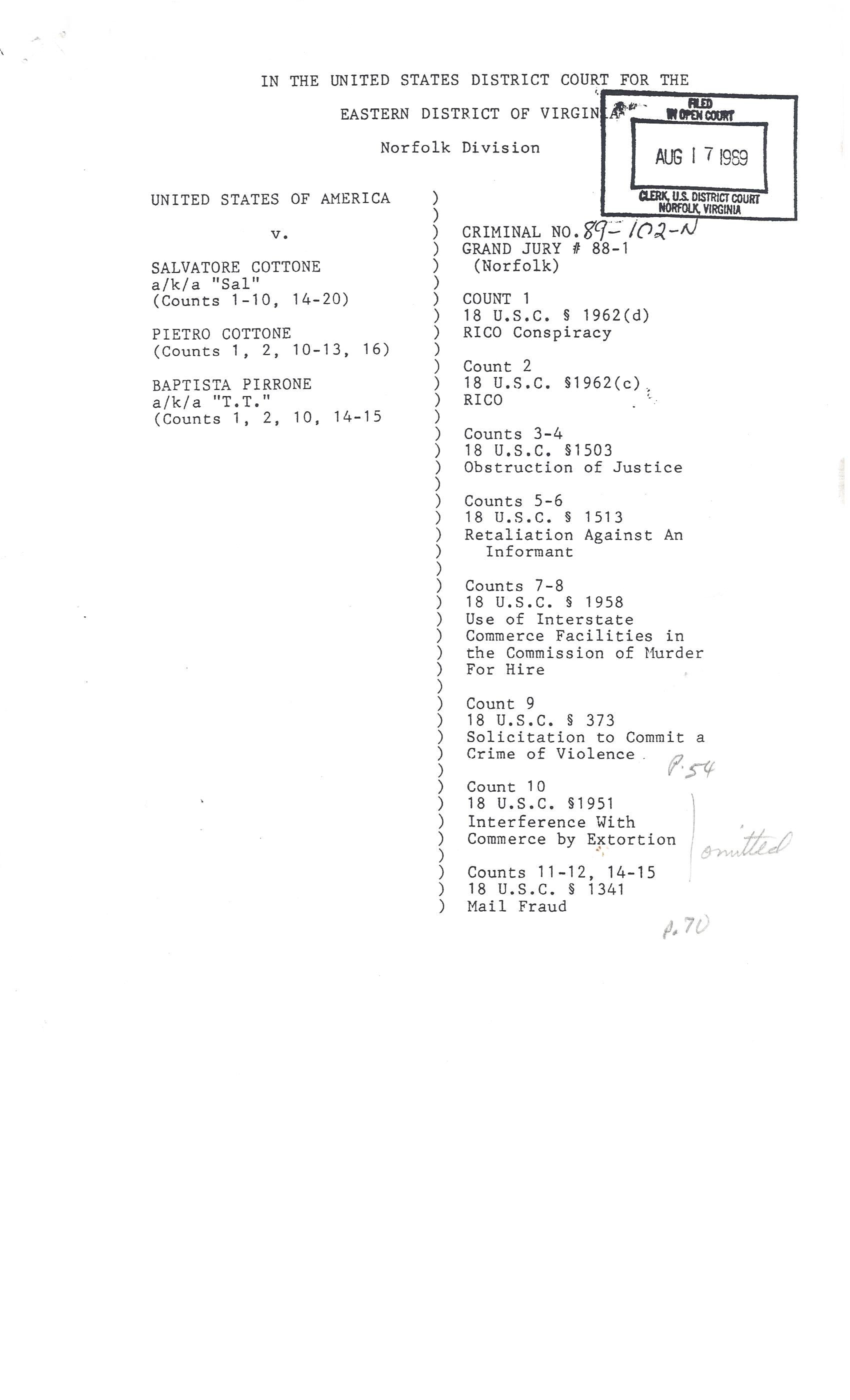

On Friday, August 25, 1989, ten months after Cottone had celebrated Casali’s death in the backroom of Michaelangelo’s, the FBI arrested Salvatore Cottone, his older brother, Pietro, and one other Cottone associate, Baptista Pirrone, at their houses in Virginia Beach. Glass personally took Cottone into custody, “with my pistol drawn” he says. “It was euphoria.”[29] Cottone was the principal defendant, and was charged with 17 felonies, dating back to the arson of Bassin’s in 1978. Other charges included obstruction of justice, wire fraud, and, of course, murder-for-hire.[30] While some testified to Cottone’s character — the Cottone brothers “would give you the shirt off their backs,” said one unnamed Michelangelo’s employee — the situation did not look good for the forty-three-year-old mafioso. It would only get worse as 1989 drew to a close.

On October 5, Pietro Cottone cut a deal with the government, pleading guilty to mail and bank fraud in exchange for prosecutors dropping the more serious racketeering charges against him. He did not agree to turn state’s evidence against his brother.[31] A few months later, the third man who had been arrested, Baptista Pirrone, followed suit, but unlike Pietro, he was willing to testify against Cottone.[32] Only Salvatore Cottone, defiant as ever, remained to fight the charges.

The trial began on January 5th, 1990. Cottone’s initial display of confidence in the Norfolk, Virginia courtroom made an impression upon those who witnessed the trial. One reporter described how the “swaggering” Cottone “portrayed himself as a grateful immigrant swelling with red, white and blue patriotism,”[33] while another noted how Cottone “wore broad smiles and waved periodically to his family.”[34] Cottone’s smile, however, “soon dissolved into a tense, straight line.”[35] For the government’s case against him was more than just the word of Alfredo Toriello and Vincenzo Hakanjin against Cottone’s. During the years that the FBI had investigated Cottone, Glass’s agents had tailed him, even slept outside his house. Federal agents had so many different wiretaps on Cottone and his associates that they created a color scheme to help the jury tell them apart. The prosecution trotted 24 pounds of cocaine into the courtroom and translated for the jury a litany of Cottone’s Sicilian threats, clandestinely recorded by FBI turncoats.[36]

The portrait they painted of Cottone was damning. Toriello stated that Cottone had wanted to retaliate against Pietro’s insubordination by beating Pietro’s wife. Another witness testified that Cottone had threatened to cut up the children of a former associate to punish him for unpaid debts. Cottone’s attempts to portray himself as a hardworking but honest “gentleman of business,” in his own words, proved to be less compelling than the portrait of the vengeful and violent career criminal that emerged through the government’s case against him. Even those that spoke in his defense worked against him: one man, Anthony Del Sordi, Jr., testified that Cottone was “a good-hearted guy” — but only because he had helped Del Sordi burn his own restaurant down as part of an insurance scam.[37]

At the end of the eleven-day trial, the jury found him guilty of 14 felonies, including the arson of Bassin’s, and his attempted hit on Lanfranco Casali.[38] Cottone’s fate in court was the “death of a thousand needles,” says Smythers of the case he helped prosecute nearly thirty years ago, “we had so many ways of putting it to him. He had just done so many crooked things.”[39] The presiding judge agreed. On March 26, 1990, at the conclusion of the region’s largest mafia case, he sentenced Salvatore Cottone to twenty years in federal prison.[40]

Operation Infamita, as it was known in the FBI, came at historic time in the bureau’s war on the Mafia. Four years previously, in the historic “Commission” case, the FBI targeted the heads of the so-called Five Families of New York. The case was notable for its extensive use of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations, or RICO, act, which allowed federal investigators to more effectively target the leaders of criminal enterprises. The case was also notable because it marked the first-time purported mafiosi admitted to the existence of the mafia organization and hierarchy in a courtroom.[41] Across the country, mafia organizations were undermined by extensive undercover operations and an increased disregard for “omerta” — or the code of silence — among lower-level criminals within the mafia organization.

Salvatore Cottone was released from federal prison in February of 2007. While the D.C. drug trade doesn’t seem to be going away any time soon, the region has not since experienced an infiltration of the Sicilian mafia. The case let would-be mafiosi know “they couldn’t just run rough-shod over everybody,” says Smythers. “We were worried [the jury] wouldn’t take this seriously because it sounded so much like a movie. This is serious, these guys will kill you.”[42]

Footnotes

- ^ Michael Smythers, phone interview by author, September 25, 2019.

- ^ Robert Howe, “’Pizza Connection’ Mastermind Convicted in VA.,” Washington Post, January 23, 1990. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1990/01/23/pizza-connectio…

- ^ James Glass Jr., phone interview by author, October 21, 2019.

- ^ Harry Jaffe and Bob Rast "So You Think There Are No Wiseguys in Washington? Wise Up. The FBI Has Collared a Kingpin of Organized Crime, and It Thinks the Capital is ... MOBBED UP," Regardie's Magazine, November 1989.

- ^ Howe, “’Pizza Connection’ Mastermind Convicted.”

- ^ Jaffe and Rast, “So You Think There Are No Wiseguys”; Greg Raver-Lampman, “’Butcher’ Testifies Against Cottone,” Virginia Pilot, January 9, 1990.

- ^ Raver-Lampman, “’Butcher’ Testifies Against Cottone.”

- ^ LaBarbara Bowman and Alfred Lewis, “Predawn Fire Guts Bassin's: Possibility of Arson Probed” Washington Post Metro, October 18, 1978.

- ^ Penny Bender, “Witness Had 2nd Thoughts”, Daily Press (Newport News, VA), January 9, 1990.

- ^ Smythers, interview.

- ^ Greg Raver-Lampman, “Butcher Says Cottone Hired Him For Crimes,” The Virginia Pilot, January 4, 1990.

- ^ Penny Bender, “FBI Informant Testifies How He Faked Murder for Hire,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), January 10, 1990.

- ^ Nancy Lewis and Carlyle Murphy, “Organized Crime Ties Found Here; Pizza Parlors Linked to Colombian Drug Ring” Washington Post, February 3, 1987.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Howe, “’Pizza Connection’ Mastermind Convicted.”

- ^ Glass, interview.

- ^ Jaffe and Rast, “So You Think There Are No Wiseguys.”

- ^ Smythers, interview.

- ^ Glass, interview.

- ^ Smythers, interview.

- ^ Howe, “’Pizza Connection’ Mastermind Convicted.”

- ^ Glass, interview.

- ^ Smythers, interview.

- ^ Penny Bender, “FBI Informant Testifies How He Faked Murder for Hire,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), January 10, 1990.

- ^ Greg Raver-Lampman, “Cottone Hired Him, ‘Killer’ Says,” The Virginia Pilot, January 10, 1990.

- ^ Penny Bender, “Norfolk Mobsters Duped, FBI Says,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), August 29, 1989.

- ^ Glass, interview.

- ^ Bender, “FBI Informant Testifies,”; Howe, “’Pizza Connection’ Mastermind Convicted.”

- ^ Glass, interview.

- ^ U.S. v. Salvatore Cottone indictment. Courtesy of Mike Smythers.

- ^ Penny Bender, “Cottone Brother Pleads Guilty,” Daily Press, October 6, 1989.

- ^ Penny Bender, “Man Pleads Guilty in Racketeering Case: Pirrone Admits to Bank, Mail Fraud,” Daily Press, December 16, 1989.

- ^ Howe, “’Pizza Connection’ Mastermind Convicted.”

- ^ Penny Bender, “Pizza Case Reveals Violent Mob Life,” Daily Press, January 16, 1990.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Penny Bender, “Ex-Restaurateur to Serve 20 Years,” Daily Press, March 27, 1990.

- ^ Raver-Lampman, “Cottone Hired Him.”

- ^ Howe, “Pizza Connection.”

- ^ Smythers, interview.

- ^ Bender, “Ex-Restaurateur to Serve.”

- ^ Peter Reuter, “The Decline of the American Mafia,” National Affairs, July 1995. https://www.nationalaffairs.com/public_interest/detail/the-decline-of-t…

- ^ Smythers, interview.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)