What's in a Name? Chevy Chase

First, I’ll debunk the obvious: this Maryland suburb isn’t named for a comedian. Though most Americans (and Google) associate the name with Cornelius “Chevy” Chase, the actor of National Lampoon fame, those of us in the D.C. area know that Chevy Chase, Maryland had it first. Rumor has it, though, that Chase’s nickname—given to him as a child by his grandmother—is actually derived from our Chevy Chase.[1] Another theory, entertained by Chase himself, is that the man and the town actually get their names from the same place: an English ballad that’s at least 500 years old.

Many of our local place names have colonial origins, since landowners tended to give their properties creative names. The land that is now Chevy Chase (both in Maryland and D.C.) was once a 560-acre parcel of land known as “Cheivy Chace,” deeded to Colonel Joseph Belt on July 10, 1725 by Charles Calvert, Lord Baltimore.[2] It was Belt who probably thought of the name for his new property, though we don’t know how he chose it. To modern eyes, it may seem a bit random—without any personal connections (like a family name) or nods to local geographical features. But Belt’s contemporaries—all English settlers and their descendants—probably understood the pop culture reference. “Cheivy Chace” references “The Ballad of Chevy Chase,” a folk ballad popular in Scotland and northern England.[3] Maybe Belt named his new home after his favorite song.

“The Ballad of Chevy Chase” tells the (largely fictionalized) story of a battle in the Cheviot Hills, on the Anglo-Scottish border. At the time, England and Scotland were still separate countries, ruled by different monarchs, and known for frequent clashes. The Earl of Northumberland, an English nobleman, decides to take a large hunting party into the hills. The Scottish Earl Douglas, who has banned hunting in his domain, believes that Northumberland is actually trying to invade Scotland. A horrific battle ensues, in which only 110 men survive. Among the dead is Douglas—though he dies a hero, knowing that his men have won the battle.[4] For the Scots, it’s a rousing song of victory against the pesky English; for the English, it’s a warning to be wary of the bloodthirsty Scots. Decide for yourself: read the lyrics here or listen to a modern interpretation of the ballad.

Since the ballad was sung and recited long before it was ever written down, historians aren’t exactly sure how old it is. Some guess that it dates from the fifteenth century and references skirmishes fought in that time, though it could be even older.[5] It became extremely popular and well-known throughout England and Scotland—in the sixteenth century, when books of ballads began being printed, this one was frequently included in the collections. Evidently, the song’s tune was also familiar to the average Englishman, because many early songbooks ask users to sing “to the tune of Chevy Chase.”[6] Being an old folk song, some of the ballad’s details change depending on the source—the lyrics, the names of the warring earls, the name of the battle, even the title itself. One thing stayed the same, though: most people agreed that the story took place in the “chase,” or hunting ground, of the Cheviot Hills. So, though some called the song by various titles, its most enduring name was “The Ballad of Chevy Chase.” It’s the name that Joseph Belt obviously knew well.

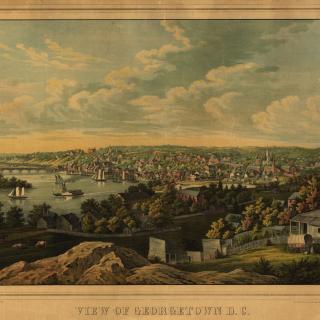

There aren’t many traces of “Cheivy Chace” left. Belt’s home, near present-day Chevy Chase Circle, was demolished after his death. His descendants broke up and sold off the original 560-acre tract. In the 1790s, the creation of the District broke up the original land even further.[7] But despite all this, Belt’s name seems to have stuck. As the area began to develop, both inside and outside the District line, the local roads and communities still referred to their home as “Chevy Chase.”

In the 1880s, when Washington’s population was booming, Senator Francis G. Newlands of Nevada decided to turn the Chevy Chase area into the suburb we know today. He used his own wealth (consisting of gold and silver mined in the West) to buy farmland in Maryland and the District, connected to downtown by the expanding streetcar network.[8] After acquiring nearly 1,700 acres of land, Newlands founded a private company to oversee the construction of his new suburban area. Rather appropriately, he named it the Chevy Chase Land Company.[9] Unfortunately, the name doesn’t always have positive connotations, since Newlands was determined to prevent poor families and minority groups from living in his community. He wanted an idyllic, gentrified suburb—an ideal reinforced by the traditional English and colonial name.

Today, though, few people realize the link between their home and a Medieval ballad. They don’t remember the land owned by Joseph Belt, which lent its name to the different areas known, respectively, as Chevy Chase. The community still exists on both sides of the Maryland-Washington line, largely within the borders of the original land—ironic, considering that the tract’s namesake was a ballad about a border skirmish. Maybe it’s time for a revival of traditional English music in the D.C. area.

Footnotes

- ^ “Chevy Chase,” Biography, https://www.biography.com/actor/chevy-chase

- ^ The Town of Chevy Chase: Past and Present (Chevy Chase: The Town of Chevy Chase, Maryland, 1990), 8.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “The Ballad of Chevy Chase,” Luminarium: Anthology of English Literature, http://www.luminarium.org/medlit/medlyric/chevychase.htm

- ^ Ruth Perry, “War and the Media in Border Minstrelsy: The Ballad of Chevy Chase,” in Ballads and Broadsides in Britain, 1500-1800, ed. Patricia Fumerton, Anita Guerrini, and Kris McAbee (Ashgate Publishing, 2010), 251.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Town of Chevy Chase, 9.

- ^ Town of Chevy Chase, 11.

- ^ Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)