Game, Set, Match: How Arthur Ashe Made Tennis Accessible in Washington

“I told you they wouldn’t let me in.”

Said with a shrug to his cousin, too young to understand the significance of this event, eight-year-old Arthur Ashe walked away from Byrd Park in his hometown of Richmond, Virginia. Young Ashe had been hoping to sign-up for the local youth tennis tournament but was turned away - not because he wasn’t good enough, but because he was black. In 1952, Richmond was still deeply segregated, and public establishments, such as the “whites only” tennis courts at Byrd Park reflected that.[1] This act of racism, being one of the earliest instances he faced during his tennis career, would certainly not be his last. But Ashe would later come back to it as a turning point in his understanding of accessibility. As he battled discrimination to become a tennis superstar as an adult, accessibility would become a large focus of Ashe’s public service – and one of the communities he served was Washington, D.C.

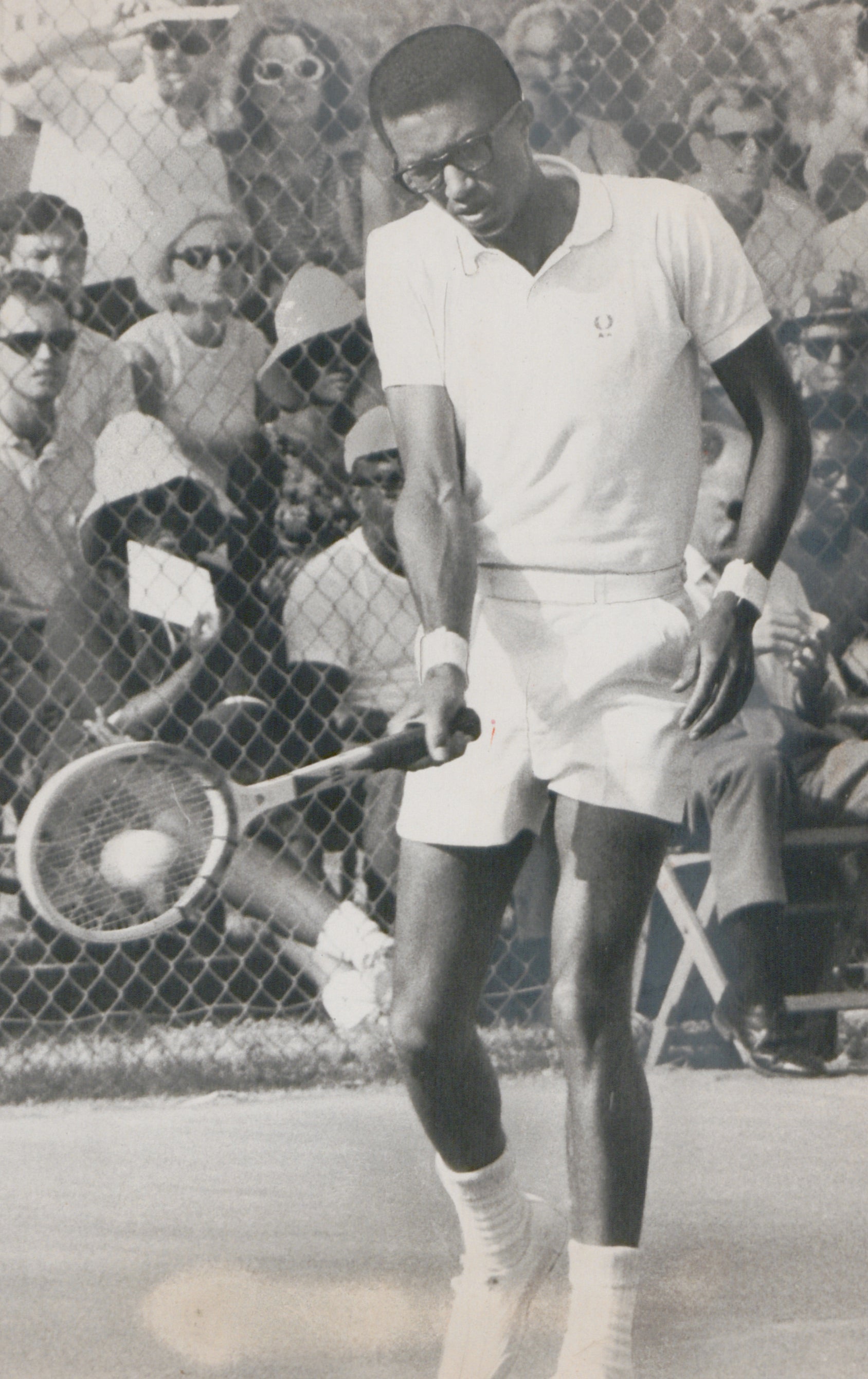

Arthur Ashe’s D.C. connection started when he came back to the east coast after graduating from UCLA. While in college, his tennis career had taken off as he competed for the university and became the first African American member of the U.S. Davis Cup team.[2] But in true Ashe fashion, he took on more and joined the Army. He accepted an appointment at West Point, but continued to play tennis and made a visit to D.C. in 1967.[3]

That August, Ashe agreed to participate in a tournament hosted by the D.C. Recreation Department’s summer enrichment program. Hosted near Lincoln Park between A and 14th Streets in Northeast D.C., the goal of this “block party” was “to bring tennis to youngsters who have never watched the game.”[4] A strong proponent of tennis and education, Ashe took to this cause immediately, teaching children in the neighborhood how to hit the ball, even playing in impromptu matches with them. This was exciting for the children, to play with an amateur tennis star who was on his way to turning pro. More excitement came later though when two other well-known tennis players, Charlie Pasarell and Donald Dell, as well as Senator Bobby Kennedy, showed up to play doubles with Ashe. Kennedy, in an outfit that looked like he came right from Capitol Hill, played four sets as Ashe’s teammate to the entertainment of the crowd. Although the event was cut short due to rain, Ashe and the others were able to hand out rackets to the excited children now interested in a sport that had previously not been in their lives.[5]

While this was a feel-good moment for many, it left Ashe unsettled. He saw that this represented a greater issue, which was the lack of accessibility this predominantly black neighborhood had to tennis. Newspapers reported that 70% of the 400-person crowd had never seen a tennis match before, and quoted Ashe as saying “These one-shot deals don’t help. These people don’t know who I am. This must be followed up.”[6] The Baltimore-based Afro-American reiterated Ashe’s concerns stating “It was fun for all and did just what the sponsors hoped it would - help enrich the athletic and cultural background of those who attended. Ashe hit the keypoint however, when he suggest a repeat performance.”[7] The sponsors of the event stated that they would “try” to make this a repeated function. However, trying wasn’t good enough for Ashe.[8]

After his experience at the block party, Ashe knew he had to do something to help the local community and neighborhoods in D.C. increase their access to tennis. In 1968, he contacted a longtime friend and eventual sports agent, Donald Dell. Ashe told Dell that he thought that there should be a tournament in D.C. However, this tournament should not be like others, which were largely played in private clubs. It should be played in a public park in an integrated neighborhood.[9] Dell agreed that it would be an important distinction to make in the D.C. tennis scene. Both men recognized that this tournament would not bring tennis to D.C.; the sport already existed in the city, however, higher-level matches typically could only be found at exclusive country clubs or other private events. Ashe knew these limitations first-hand and saw the benefits of public exposure not only reflected in his personal success but in his participation in the block party. So, Ashe told Dell, if Dell could get a professional-level tournament in D.C. and “black faces come out to watch tennis” Ashe would play in that tournament every year.[10]

By the summer of 1968 Dell, along with tournament co-founder John Harris, had found the perfect spot: the courts at 16th and Kennedy Streets NW in Rock Creek Park. They were in a National Park, meaning they were accessible and public to all. Here, there were no restrictions on who could come to enjoy a match. Additionally, the courts already served a diverse community, meeting Ashe’s wishes that the tournament be hosted in an integrated neighborhood.[11] However, one question remained: would the public want to come? Ashe, Dell, and Harris soon had their answer.

On July 23, 1968, Arthur Ashe and Charlie Pasarell played at the courts at 16th and Kennedy Streets in what was considered a Davis Cup “test” match.[12] More than 2,000 attendees, including a group of kids from a local summer camp, flooded the seats, excited to see these tennis greats play each other. The Evening Star recognized the uniqueness of the event, observing that it “was an unusual sight around here with the stands bulging for a tennis match” especially considering that the “game wasn’t particularly important as the world of tennis scene goes.”[13] In a way, that was the point. Though the match may not have been important in terms of tournament ranking or individual player success, scores of Washingtonians – including many black Washingtonians – came to watch. This was a strong indication that increased accessibility to tennis could inspire new fans to become interested in the sport, not just in watching but in playing. Overall, Ashe and Dell’s test had been a success and it was time to bring the tournament to D.C.

In 1969, the Washington Star International tournament first premiered at the courts at 16th and Kennedy Streets, NW. Ashe stayed true to his word – he played in the tournament not only that first year but for the next eleven years. Right from the beginning reporters were asking what Ashe had been thinking all along, “Why shouldn’t championship tennis be brought to the inner city?”[14]

These questions from reporters were coming at a pivotal time in D.C.’s history. The District’s population was changing dramatically. In 1950, the city recorded its highest population ever – over 802,000 residents, 64% of whom were white. With the expansion of highways during the 1950s and ‘60s, many residents – particularly whites – moved to the suburbs. The shift accelerated after the 1968 riots, which ravaged several inner city D.C. neighborhoods following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Meanwhile, the number of African American residents in Washington was increasing dramatically. By 1970, the number of black D.C. residents had nearly doubled (as compared to 1950), and the overall population of the city was 71% black.[15]

Speaking to reporters at the inaugural tournament, Donald Dell captured Ashe’s motivation to bring the game to new audiences, “The trouble with tennis…is that it’s always been the sport of the privileged few. And unless the game is brought to all of the people - especially the city kids who really take to the game - it will remain the sport of the few.”[16]

Ashe addressed the issue of access as well – not to the newspaper, but directly to local children. Along with playing in the professional tournament, Ashe spent time teaching clinics and playing with the local kids. He played on the Banneker courts near Howard University, telling the children that he came from a similar neighborhood in Richmond, and even played on these exact courts when he traveled to D.C. at ten years old and was just getting started with the sport.[17] He wanted these kids to know that anything was possible, and if they wanted, they had a future in tennis, stating “I’ve travelled all over the world; I’ve finished college; I’ve been in the Army…I know it sounds funny, but you’re looking today at living proof of what tennis can do for you.”[18]

The impact was lasting – in ways that even Ashe may not have even imagined back in 1969. In 1972, Donald Dell and tournament co-founder John Harris gave the sanction of the tournament to the Washington Tennis and Education Foundation, a group that “promotes tennis and education among at-risk youth”.[19] The Foundation not only provides free tennis summer camp for 160 kids – primarily African American children in Southeast, DC – but also provides them with after school programs and educational support.

Now, over 50 years after Ashe and Dell brought professional tennis to Washington, the tournament they started is known as the Citi Open. It’s a highlight of the summer sports calendar in Washington but education and accessibility remain the central focus of the Foundation. As former WTEF President Rebecca Crouch-Pelham told WAMU in 2018, “Our mission is completely aligned to why Arthur Ashe even brought the Citi Open here in the first place”.[20]

Game, set, match, Arthur Ashe.

Footnotes

- ^ Raymond Arsenault, Arthur Ashe: A Life (Simon and Schuster, 2018), 20.

- ^ Arsenault,136.

- ^ Arsenault, 180.

- ^ Mark Asher, “Ashe to Play Tennis At Block Party Here,” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), August 2, 1967, sec. Sports.

- ^ Mark Asher, “Youngsters Discover Rackets at Block Party,” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), August 4, 1967, sec. Sports.

- ^ Asher.

- ^ “Ashe Anxious to Repeat Tennis Tips for Youths,” Afro-American (1893-), August 12, 1967.

- ^ Asher, “Youngsters Discover Rackets at Block Party.”

- ^ Jacob Feldman, “Arthur Ashe Helped Establish Washington’s pro Tennis Tournament,” Washington Post, August 1, 2015, sec. Sports.

- ^ Feldman.

- ^ Restricted Housing and Racial Change, 1940-1970 [map]. “Mapping Segregation DC”. Last Updated May 18, 2021.

- ^ Steve Guback, “Ashe Plays Pasarell on Tennis Day,” Evening Star (Washington (DC), District of Columbia), July 22, 1968: 6. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current.

- ^ Steve Guback, “Davis Cuppers Score Hit Here,” Evening Star (Washington (DC), District of Columbia), July 24, 1968: 72. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current.

- ^ “Bringing Tennis to the Playground,” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), July 11, 1969, sec. General.

- ^ Matthew B. Gilmore.“District of Columbia Population History.” Washington DC History Resources.

- ^ “Bringing Tennis to the Playground.”

- ^ M. M. Flatley, “‘Like Hammering a Nail’ Tennis Headliners Show Banneker Kids How It’s Played,” Evening Star (Washington (DC), District of Columbia), July 8, 1969: 17. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current.

- ^ Flatley.

- ^ Martin Austermuhle, “Fifty Years Ago, Arthur Ashe Helped Bring A Pro Tennis Tournament To D.C. It’s Still Going Strong.,” WAMU (blog).

- ^ Austermuhle.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)