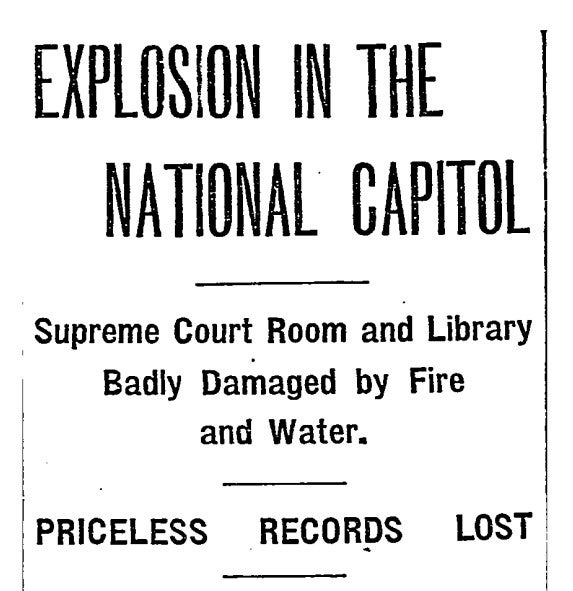

How an Electrician Saved the U.S. Capitol After the Devastating Gas Explosion of 1898

(Source: New York Times)

It was a little past 5 o’clock, and like any Sunday evening, Lieutenant Nelson of the Capitol Police was doing his rounds through the US Capitol. As he passed by the Senate wing, he noticed the strong smell of gas permeating the air. Although much of the Capitol had electric lighting by 1898, some regions still relied on gas for illumination, so getting the occasional whiff of gas wasn’t all that unusual. What was unusual was the intensity of the smell and the way it seemed to be concentrated around an elevator leading to the building’s lower levels. Suspecting a gas leak, Lt. Nelson headed south towards the House of Representatives to investigate. It was a good thing he moved when he did because by the time he crossed the Rotunda, it happened.

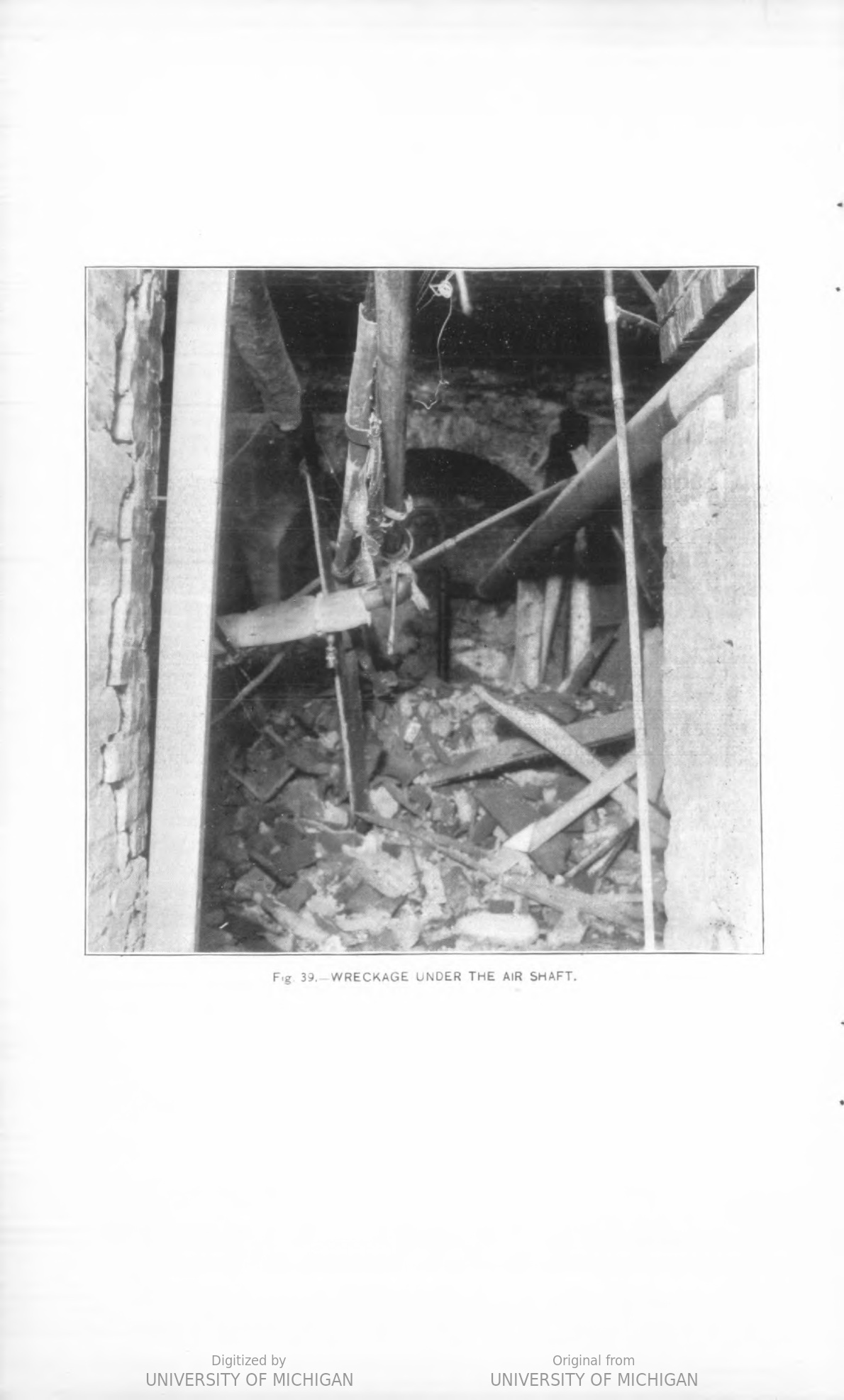

and and flames, making the job of extinguishing the

fire and navigating the basement even more difficult.

(Source: Annual Report of the Architect of the United States Capitol to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1899 via Hathi Trust)

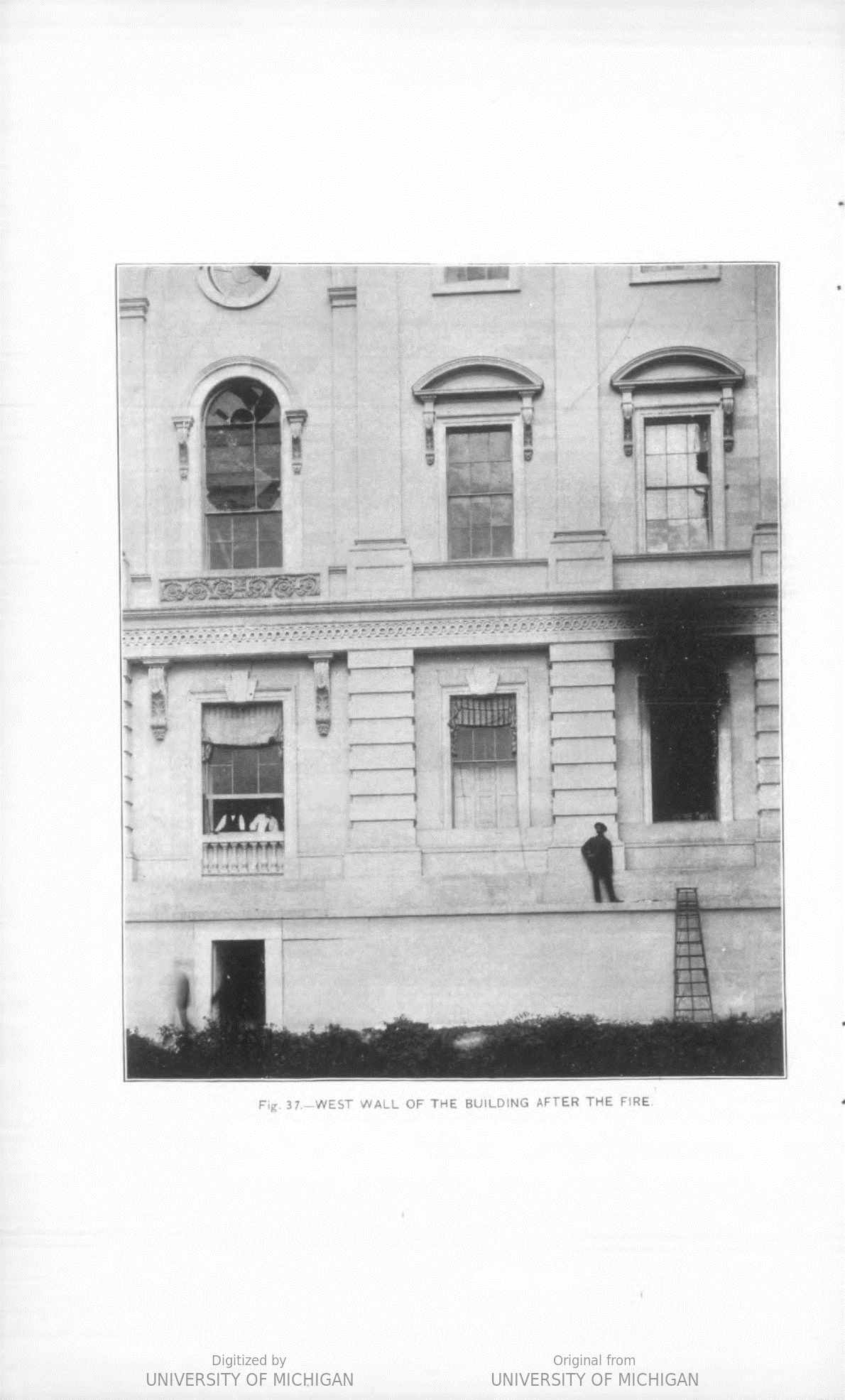

A great boom shook the floor, roaring through the halls and rocking the building. Glass shards flew as windows shattered. The unique acoustics of the Rotunda and Statuary Hall reverberated the horrific sound.1 A couple of the giant stones on the exterior of the building even shifted a few inches outwards. Lt. Nelson steadied himself. Somewhere, on one of the two floors below, something had exploded.

Nelson raced down a flight of stairs to the main basement where he met up with other employees of the Capitol, including mechanics, engineers, and patrolmen, who all seemed just as confused as he.2 As the group got closer to the origin of the noise, the scene grew ever more chaotic; chunks of stone arches blocked paths, heavy steel doors had been blown from their hinges and sent flying across rooms. But before Nelson and the others could find what had caused the blast, they discovered something even more dangerous – a fire.

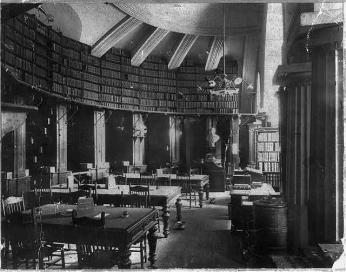

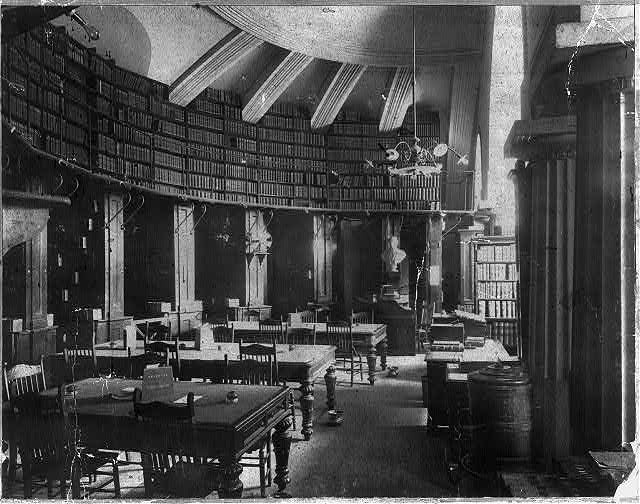

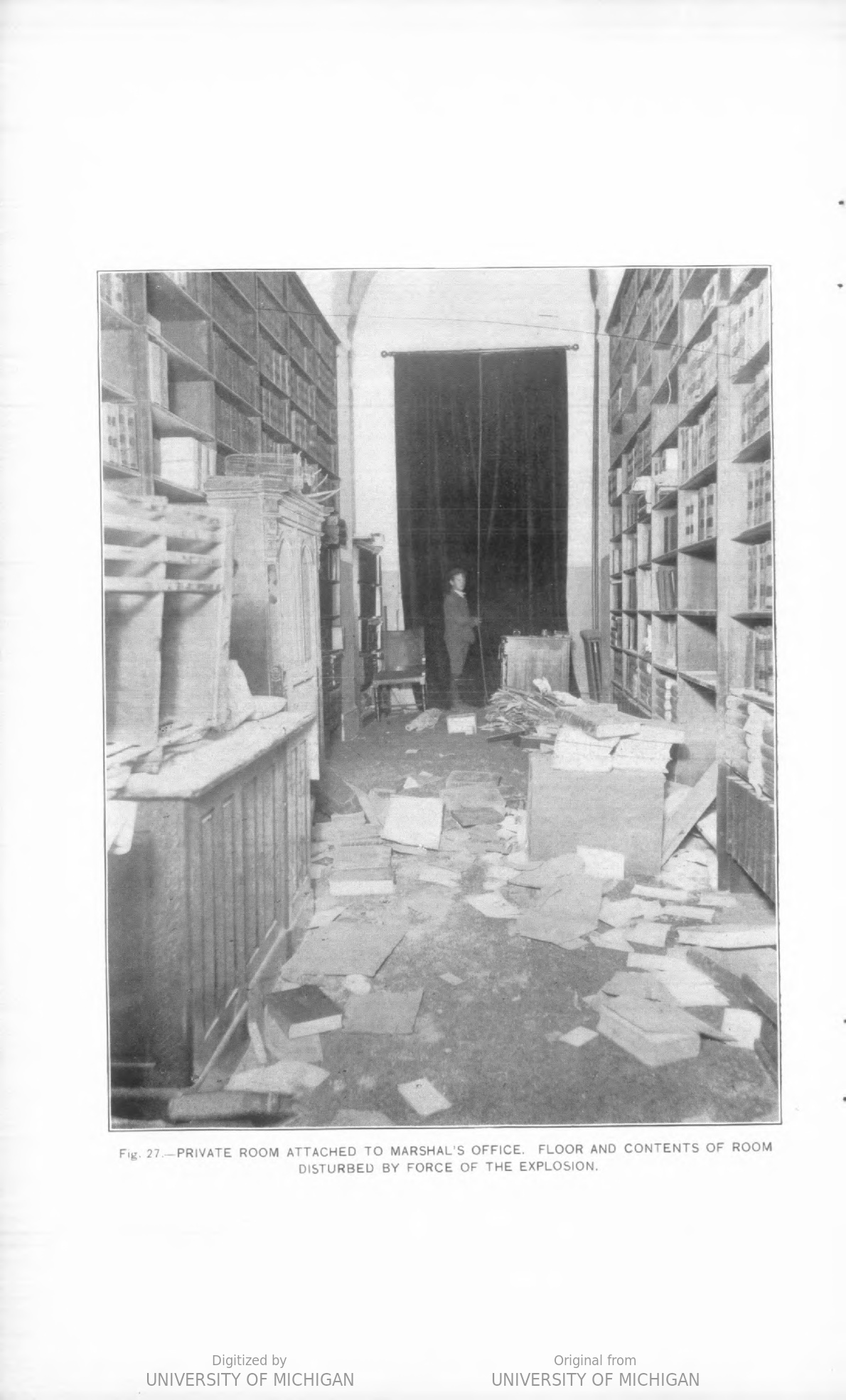

valuable law library in the world," home to more than

75,000 volumes, and the location of the first telephone

call in history, was at extreme risk from the fire.

(Source: Library of Congress Public Domain Archive)

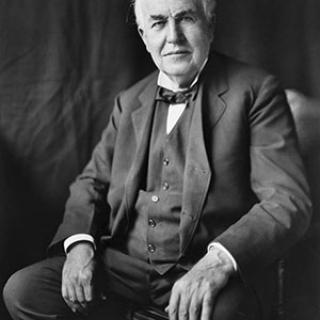

While there’s never a good time to have an explosion in a government building, the Capitol at this point in history was perhaps one of the worst places to have a destructive fire. The Supreme Court did not yet have a building of its own, so it still operated out of the basement of the Capitol, along with all the Court’s legal documents and law books. Unlike the court, the Library of Congress did have its own building, which had just been completed the previous year. But while most of the collection had been transferred from the Capitol to their new home, the law books still remained where they would be of the most use – with the court. Librarian Thomas H. Clark believed that it was the “most valuable law library in the world”.3, 4

The stakes were immensely high. A great deal of very important United States history were at risk of being lost to the rising flames.

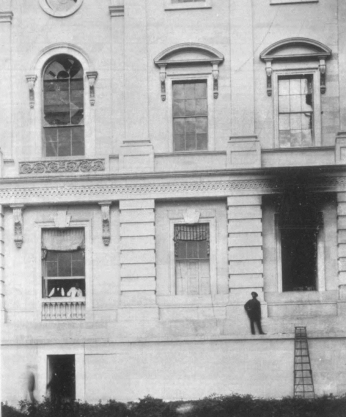

While the fire spread inside, those who heard the blast from outside ran to police boxes to alert the fire department. Nearby fire stations began to descend upon the Capitol from every direction. The Washington Times described the frantic scene:

“Great ladders, like cobwebs, rose against the white walls of the Capitol. Men, looking like brownies, were running up and down. Flames and smoke were pouring from the east windows, and the engine bells were clanging.”5

by the force of the explosion were stained

black. (Source: Annual Report of the Architect of the United States Capitol to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1899 via Hathi Trust)

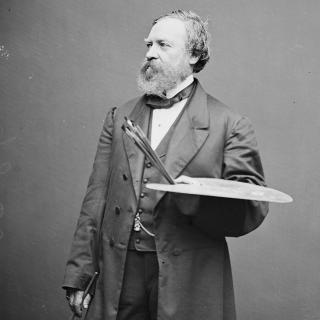

Upon entering the building, the fire chief Joseph Parris and his firemen joined the Capitol workers who were already fighting the flames. These maintenance workers proved instrumental as they were able to navigate the labyrinth of corridors in the building’s cellar. One of these men, chief electrician Christian P. Gliem, enlisted some of the newly arrived fireman to assist him on a daring mission to the very heart of the inferno.

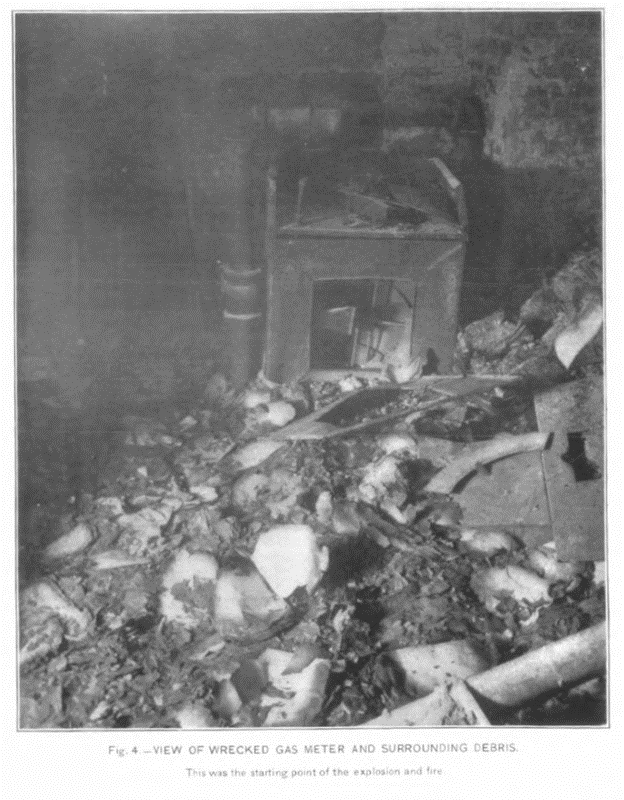

starting the fire. To the left is the main gas pipe

electrician C. P. Gliem heroically shut off.

(Source: Annual Report of the Architect of the United States Capitol to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1899 via Hathi Trust)

Fighting their way past fallen debris and smoldering law books, the small team made their way to a ruined room in the cellar. Though it was unrecognizable by the flames currently consuming it, Gliem knew this room was home to a gas meter attached to a gas main. Surrounded by the wrecked steel skeleton of the meter, that gas main was now exposed and spewing fuel. The result was a massive jet of fire crossing the entirety of room. The firefighters blasted the hellfire escaping the pipe, but there was simply too much gas being fed constantly to the fire. If they had any hope of putting an end to this nightmare, someone would have to close that pipe. Shifting their strategy, the firemen focused not on extinguishing the fire, but choking the escaping gas while cooling the surface of the pipe with a flood of water. Gliem went to his knees and crawled towards the pipe, avoiding the epic battle between fire and water overhead. He got his hands on the outlet valve and, with all his strength, twisted it shut.6

Less heroic but equally entertaining, the most absurd event of the day was occurring upstairs in the Rotunda. While a firefighter was dousing flames, his hose suddenly split open, making a “threatening sound… creating alarm among the bystanders.” The break in the line was quickly patched up, but still the hose refused to work properly. With water dripping out of the nozzle “in a limp and uncertain way,” the fireman promptly unscrewed the nozzle to see if it was blocked and, as so many great firemen before him had done, pulled four eels out of the hose. (Yes, you read that right. Surprised? Imagine how they felt!) Tossing the problem eels aside, he returned to the work at hand.7

To be certain that every last ember was extinguished, firefighters flooded the basement with water for the next two hours. Once the fire was out and the basement had been drained, the Architect of the Capitol began to assess the damage. Regarding the area where the blast originated, Munroe wrote:

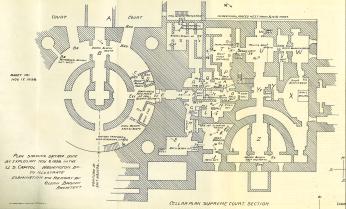

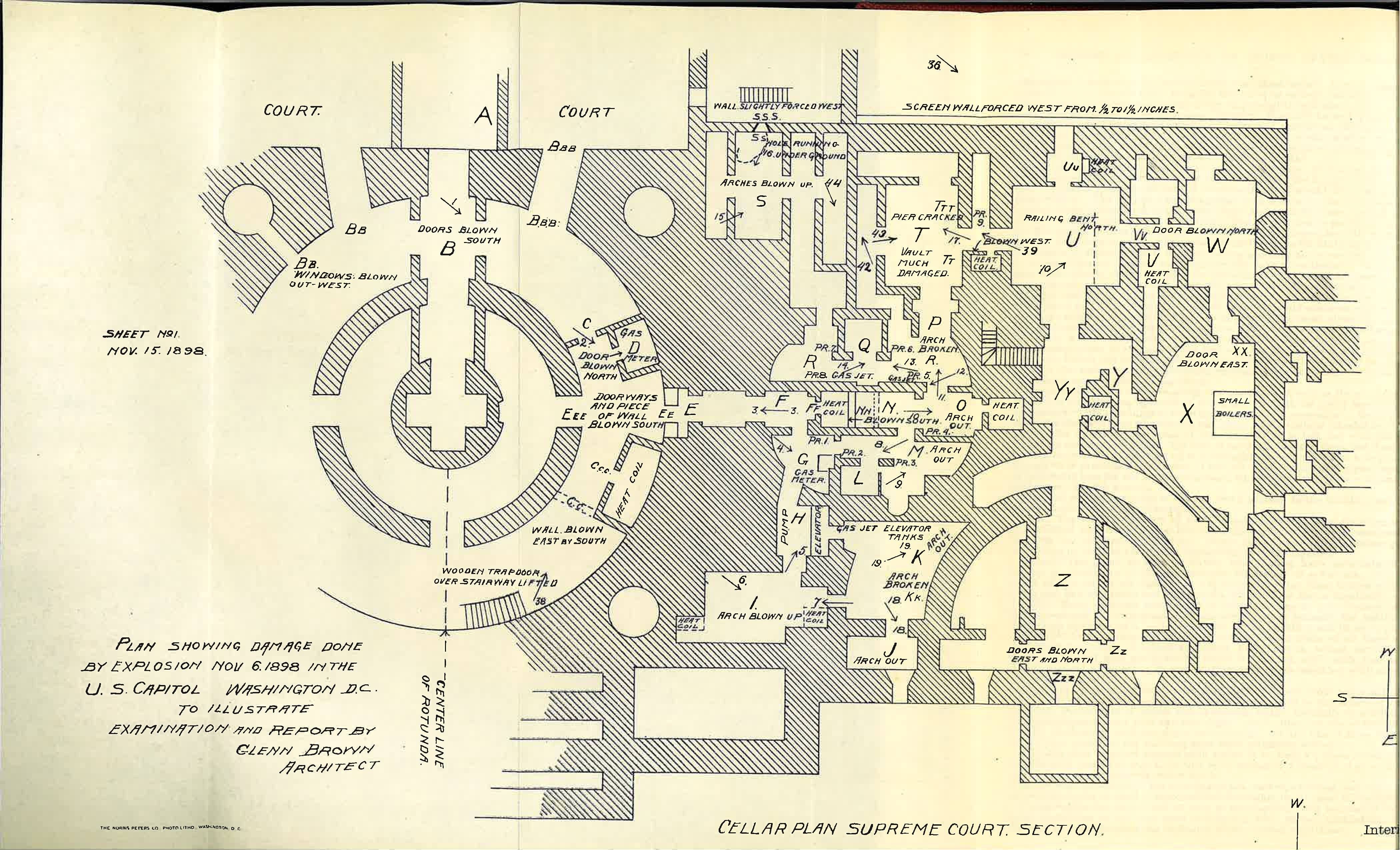

"The area affected by the explosion was very clearly defined by displaced arches and walls, distorted shelves and cases, broken doors and bulkheads, and shivered glass and sashes."8

maintenance chamber to the tomb below the crypt.

(Source: Annual Report of the Architect of the United States Capitol to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1899 via Hathi Trust)

Overall, despite the dramatic nature of the event, the destruction could have been much greater. As the explosion occurred on a Sunday afternoon, there were no casualties (save the eels, of course), and even though the force of the blast was great enough to create 20 tons of debris, the superior architecture of the old Capitol building was able to absorb a great deal of it. The investigating architect, Glenn Brown pronounced that “there could have been no better practicable construction to resist the explosion and fire than the construction which existed in the portions of the Capitol where the explosion took place.”9 But while the structural damage was limited, there were a great deal of documents consumed by the blaze. Thankfully, most were duplicates. Among the original documents that were damaged by smoke, flame, or water, the vast majority were able to be restored, much to the relief of librarian Clark.

“This library contains upwards of 75,000 volumes of rare and valuable books. Had they been destroyed the loss would, to a great extent, have been irreparable. We have here every description of law book, including old laws of the original colonies, some of them published as far back as the latter part of the seventeenth century. These books could never be replaced. As it is some considerable damage has been done, but, thanks to the efficient service of Chief Parris and his gallant men, we are saved a loss of inestimable value.”10, 11

were blown of their shelves by the explosion.

(Source: Annual Report of the Architect of the United States Capitol to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1899 via Hathi Trust)

Not all were so lucky, however. According to Supreme Court justices, the greatest loss were Court records from 1792 to 1832, all of which had been stored in the basement. Along with the documents, several busts of past justices were severally damaged or destroyed.12

If the contents of the building were so valuable, how could something like this happen in the first place? The Architect of the Capitol hired two specialists to investigate the explosion. Glenn Brown, an architect whose work can be found all throughout the District, was tasked with assessing the structural damage done to the bones of the building. Charles E. Munroe, a chemistry professor at the Columbian University (later renamed George Washington University), was brought on as an “expert on explosives”.13 While that might seem more like the title you would give to someone while planning a heist, it was certainly an appropriate fit for Munroe, who understood the mechanics of explosives so well that he discovered the “Munroe effect,” a foundational principle in the design of shaped charges (think anti-tank missiles).14, 15

like cracked arches, blown off doors, and exploded

windows are marked throughout.

(Source: Library of Congress)

According to Munroe, there were several important factors contributing to the incident. For one, while the majority of the Capitol’s lighting had been electrified, the subbasement underneath the Supreme Court had not been, so if court clerks were looking for papers stashed in the rooms below ground they had to rely on gas burners built into the wall for illumination. Those burners were frequently left alight, as was the case at the time of the explosion.16 Second, the gas meter that Gliem shut off during the fire had been made obsolete months prior and had purportedly been shut down. However, the investigation found the meter had not been closed properly, allowing a slow leak as a result. Third, the gas company reported an abnormal spike in gas pressure throughout their system just prior to the event. This extra pressure forced the old gas meter to leak much more than usual, filling the subterranean cellar with volatile vapors. The spike pushed the gas cloud to an illumination burner in the wall. When the gas combusted, a fireball raced through the air towards the leaking gas meter where it erupted into a fiery explosion which shook the temple of democracy.

The fire found ample fuel as much of the basement was crammed “from floor to ceiling… with combustible documents.”17 Nearly every wall was fitted with wooden shelves loaded with papers and books. As if this wasn’t enough, here is a list of the other flammable materials stashed in the basement at the time of the fire.18

- 10 cords (1,280 cubic feet) of firewood

- A small pile of coal weighing some 40 tons

- Multiple barrels of oil

- Flammable furniture packed together in storage

- Flammable models used as exhibitions for Supreme Court use

- Boilers, which were part of the basement’s heating system

- Pressurized tanks for elevator operation

Suffice to say, the fire did not want for fuel. The blaze ripped through the cellar, consuming everything in its path. It devoured all it could in the bottom basement before discovering the wooden skeleton of the Supreme Court elevator, which it promptly climbed in search of more stuff to burn. Thankfully, while the fire did some damage the Supreme Court chambers, the vast majority of the devastation was concentrated on the lower floors.

With the investigation concluded, the clean-up effort began. Unfortunately, Congress was set to come back in session in less than a month, leaving little time for repairs. Elliot Woods, assistant to the Architect of the Capitol, employed workers day and night in order to restore the halls in time for the lawmakers’ return.19 Miraculously, when Congress ended their recess just 30 days later, the halls had not only been repaired, but fireproofed! Tangentially, during these repairs, a cat ran through drying concrete in the Small Rotunda, leaving paw prints which would later be used as evidence of a “Demon Cat” said to haunt the building. Finally, when the subbasement was repaired, the Architect of the Capitol issued a warning to the Supreme Court:

“The present good condition can only be preserved… by such regulations on the part of the court as will prevent the subbasement from being used for storage of useless material.”20

In other words, ‘don’t fill my nice new subbasement up with crap unless you want another fire!’ The Court complied until it finally got a building of its own in 1935, free to fill with as many “useless” documents as the justices pleased. After the chaos of the 1898 gas explosion, the Capitol went relatively explosion-free for a while, at least until a German spy snuck a time bomb into the Senate 17 years later, but that's a story for another time...

Check out all 44 photos of the damage in the original report!

Footnotes

- 1

United States. “Report of the Architect of the Capitol to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1899.” Washington, D.C.: Architect of the Capitol, 1899.

- 2

Munroe, Charles E., “Report of the Fire and Explosion at the United States Capitol, on November 6, 1898." In 'Architect of the Capitol to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1899.' Washington, D.C.: Architect of the Capitol, 1899.

- 3

The Times (Washington D.C.). “Capitol Was In Danger.” November 7, 1898.

- 4 This quote may have come from librarian Henry D. Clark, article is unclear as there are multiple librarians in the story with the last name Clark.

- 5

The Times (Washington D.C.). “Capitol Was In Danger.” November 7, 1898.

- 6

United States. “Report of the Architect of the Capitol to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1899.” Washington, D.C.: Architect of the Capitol, 1899.

- 7

The Times (Washington D.C.). “Capitol Was In Danger.” November 7, 1898.

- 8

Munroe, Charles E., “Report of the Fire and Explosion at the United States Capitol, on November 6, 1898." In 'Architect of the Capitol to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1899.' Washington, D.C.: Architect of the Capitol, 1899.

- 9

Brown, Glenn, “Report of the Effects of an Explosion at the United States Capitol, on November 6, 1898." In 'Architect of the Capitol to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1899.' Washington, D.C.: Architect of the Capitol, 1899.

- 10

The Times (Washington D.C.). “Capitol Was In Danger.” November 7, 1898.

- 11 This quote may have come from librarian Henry D. Clark, article is unclear as there are multiple librarians in the story with the last name Clark.

- 12

The New York Times. “EXPLOSION IN THE NATIONAL CAPITOL.” November 7, 1898.

- 13

United States. “Report of the Architect of the Capitol to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1899.” Washington, D.C.: Architect of the Capitol, 1899.

- 14

“Charles Edward Munroe.” In Wikipedia, April 5, 2023.

- 15

Kennedy, Donald R., "History of the Shaped Charge Effect." Archived January 27, 2019 at the Wayback Machine (Los Alamos, New Mexico: Los Alamos National Laboratory, 1990), pp. 3–5.

- 16

Munroe, Charles E., “Report of the Fire and Explosion at the United States Capitol, on November 6, 1898." In 'Architect of the Capitol to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1899.' Washington, D.C.: Architect of the Capitol, 1899.

- 17

Munroe, Charles E., “Report of the Fire and Explosion at the United States Capitol, on November 6, 1898." In 'Architect of the Capitol to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1899.' Washington, D.C.: Architect of the Capitol, 1899.

- 18

Munroe, Charles E., “Report of the Fire and Explosion at the United States Capitol, on November 6, 1898." In 'Architect of the Capitol to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1899.' Washington, D.C.: Architect of the Capitol, 1899.

- 19

Brown, Glenn. History of the United States Capitol. New York, Da Capo Press, 1970. P. 172.

- 20

United States. “Report of the Architect of the Capitol to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1899.” Washington, D.C.: Architect of the Capitol, 1899.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)