Luke, I Am Your... Gargoyle? : How Darth Vader Came to the National Cathedral

If you visit Washington’s National Cathedral, you’re sure to be in awe of the soaring Gothic architecture, ornate carvings, and luminous stained-glass windows. But some of the cathedral’s quirkier sights can only be seen with a pair of binoculars. Way up on the 7th and 8th stories of the building, over 100 stone faces peek out from the edge of the roof. These are the cathedral’s gargoyles and grotesques – sculptures that help to funnel damaging rainwater away from the sides of a building. (Gargoyles’ mouths work like water spouts, while grotesques let the water roll off of their heads.1 )

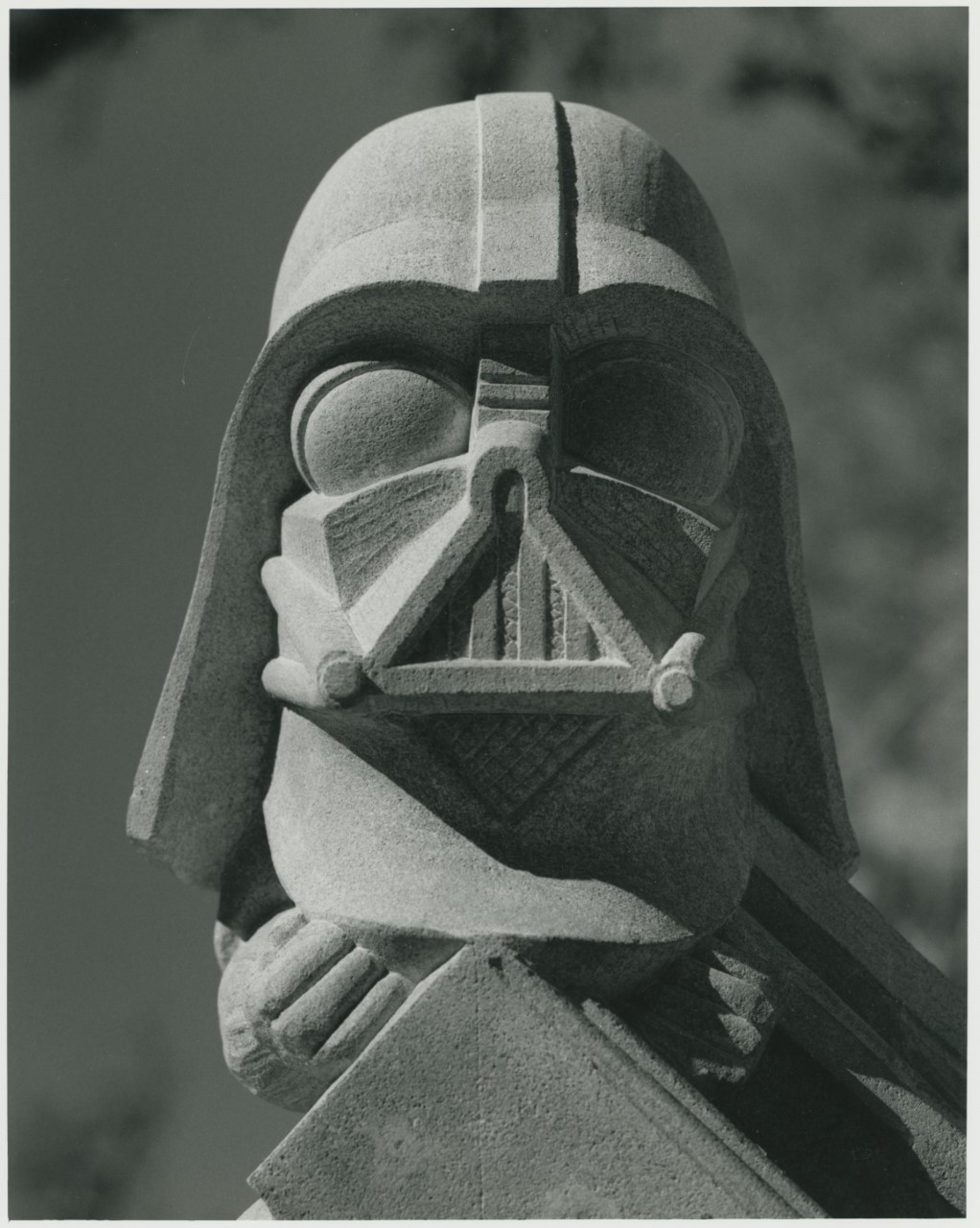

But of all the incredible sculptures, one in particular has drawn the eye of movie fans young and old since it was installed in 1986: the Darth Vader grotesque.

Darth Vader’s presence at the Cathedral stems all the way back to a desire expressed by George Washington to have “great church for national purposes”2 for Americans of all faiths. Since construction started in 1907, the Cathedral used fundraising and publicity-generating efforts to encourage all Americans to have a stake in the cathedral, and in turn in the nation’s future. But by the 1980s, it recognized that it needed to reach out to a broader constituency, including young people who had little interest in the ancient arts that inspired the cathedral.3

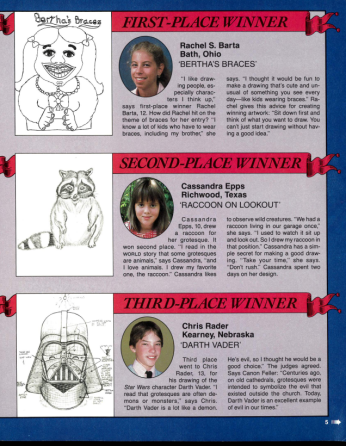

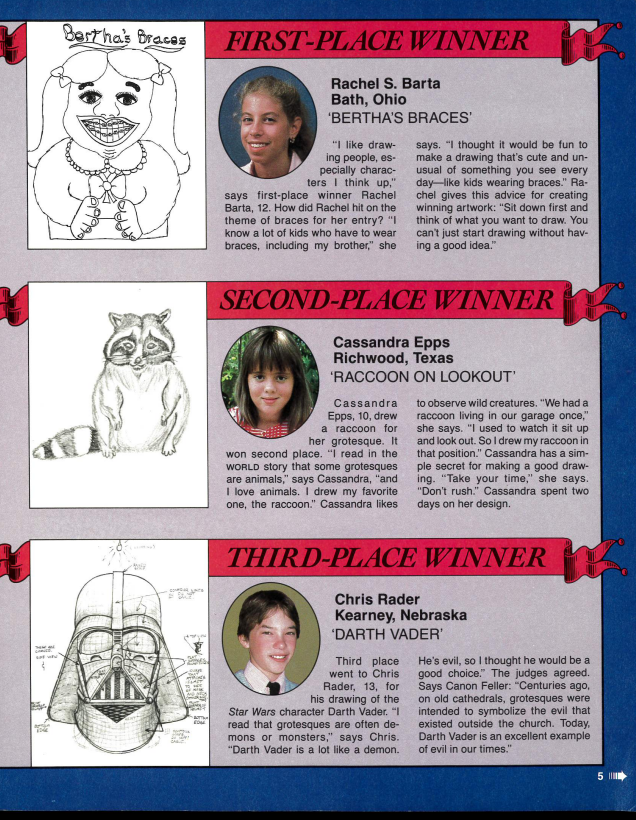

In an effort to raise children’s interest in the Cathedral, it sponsored trips for local children to visit, and developed programs on history and the arts.4 In the April 1984 issue of National Geographic World (now National Geographic Kids), the Cathedral publicized a Design-A-Grotesque competition for schoolchildren from all over the world. 1,400 children sent in submissions from 16 countries, including Czechoslovakia, Israel, and Australia. The winners were announced in the February 1986 issue.5

The idea for a Darth Vader grotesque was submitted by 13-year-old Chris Rader of Nebraska. Contrary to what you may believe, it wasn’t the grand prize winner, but one of three runners-up. The winning design was of a toothy creature holding up an umbrella. The artist, 12-year-old Alison Garner, told National Geographic “I read that rainwater drains out of the mouths of gargoyles, so I gave my grotesque an umbrella for protection.”6

Fortunately for Star Wars fans, contest organizers decided to carve the top four submissions and add them to the building’s façade. So, following the contest, sculptor Jay Hall Carpenter (the Cathedral’s first sculptor-in-residence) used Chris Rader’s drawing and still frames from the Star Wars movies to sculpt the Vader helmet out of clay. Then stone carver Patrick J. Plunkett chiseled the grotesque from limestone.1

Rader’s design was far more technical than the rest of the submissions, with labels that gave clarifying information to Carpenter and Plunkett. Explaining his choice of design, Rader said, “I read that grotesques are often demons or monsters. Darth Vader is a lot like a demon. He’s evil, so I thought he would be a good choice.”2

Rader was right, Darth Vader was a good choice, and in more ways than he probably realized. It may seem anachronistic, even sacrilegious, to adorn a holy building with a pop culture movie villain, but Vader is actually a perfect fit for the cathedral.

The cathedral was built in the style of a 14th-century Gothic cathedral, but it was always meant to reflect modern America. According to Robert Calhoun Smith, a senior partner in the cathedral’s architectural firm, the cathedral, “uses contemporary art and sculpture” which “accurately reflects the spirit of the 14th century, when cathedrals used contemporary art, [more] than would mere imitation of that art.”3 The costume design for Darth Vader is one of the most recognizable silhouettes of the 20th century. If that’s not art, what is?

In addition to reflecting contemporary aesthetics and culture, Vader has a symbolic meaning too. Richard T. Feller, the cathedral’s historian, reflected, “Centuries ago, on old cathedrals, grotesques were intended to symbolize the evil that existed outside the church. Today, Darth Vader is an excellent example of evil in our times.”4

Across the films that make up the original Star Wars trilogy, Darth Vader begins as a ruthless, irredeemable villain until it is revealed that he is the father of the heroic Luke Skywalker. Vader tempts Luke to join the dark side while Luke tries to convince him to renounce his villainous ways. In the end (spoiler alert!) good conquers evil, but not before Vader can die a redemptive death in his son’s arms. Darth Vader may represent evil, but he also represents the power of good over evil, and the choice that one person can make between the two. Now that sounds like a moral tale fit for a cathedral.

So, what would the cathedral’s original architects and masons think of a Hollywood Sith Lord adorning their Gothic-inspired building? Our guess is that they would be pleased. When ground broke on the Cathedral in 1907, everyone who worked on the building recognized that it would far outlive them, and would evolve with each new set of hands that shaped its stone. As Francis Syre, longtime Dean of the Cathedral once remarked, “We are building an instrument that can be far more eloquent and permanent than all the sermons in the world.”5 Peter Cleland, the cathedral’s master mason in 1986, said, “I tell my men: Take your time—you’re building something to last 2,000 years.”6 The National Cathedral was originally conceived to connect people of all faiths, but it also connects past and future, fiction and reality, and even Tatooine and Earth.

Footnotes

- 11 “The Winners of World’s Draw-A-Grotesque Contest.” National Geographic World. April 1984. Courtesy Washington National Cathedral, Record Group 133, Box 6, Folder 11.

- 22 Jim Castelli. "Stonesetting to Resume at Cathedral." Evening Star. Sept 25, 1980.

- 33 Marjorie Hyer. "Cathedral roof gets final fantastic figure." Washington Post. Dec 17, 1987.

- 44 Ibid.

- 55 “The Winners of World’s Draw-A-Grotesque Contest.” National Geographic World. April 1984. Courtesy Washington National Cathedral, Record Group 133, Box 6, Folder 11.

- 66 Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)