How Washington's Modern Art Movement Became Cold War Artillery

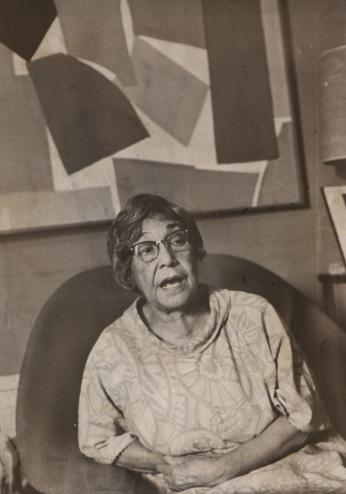

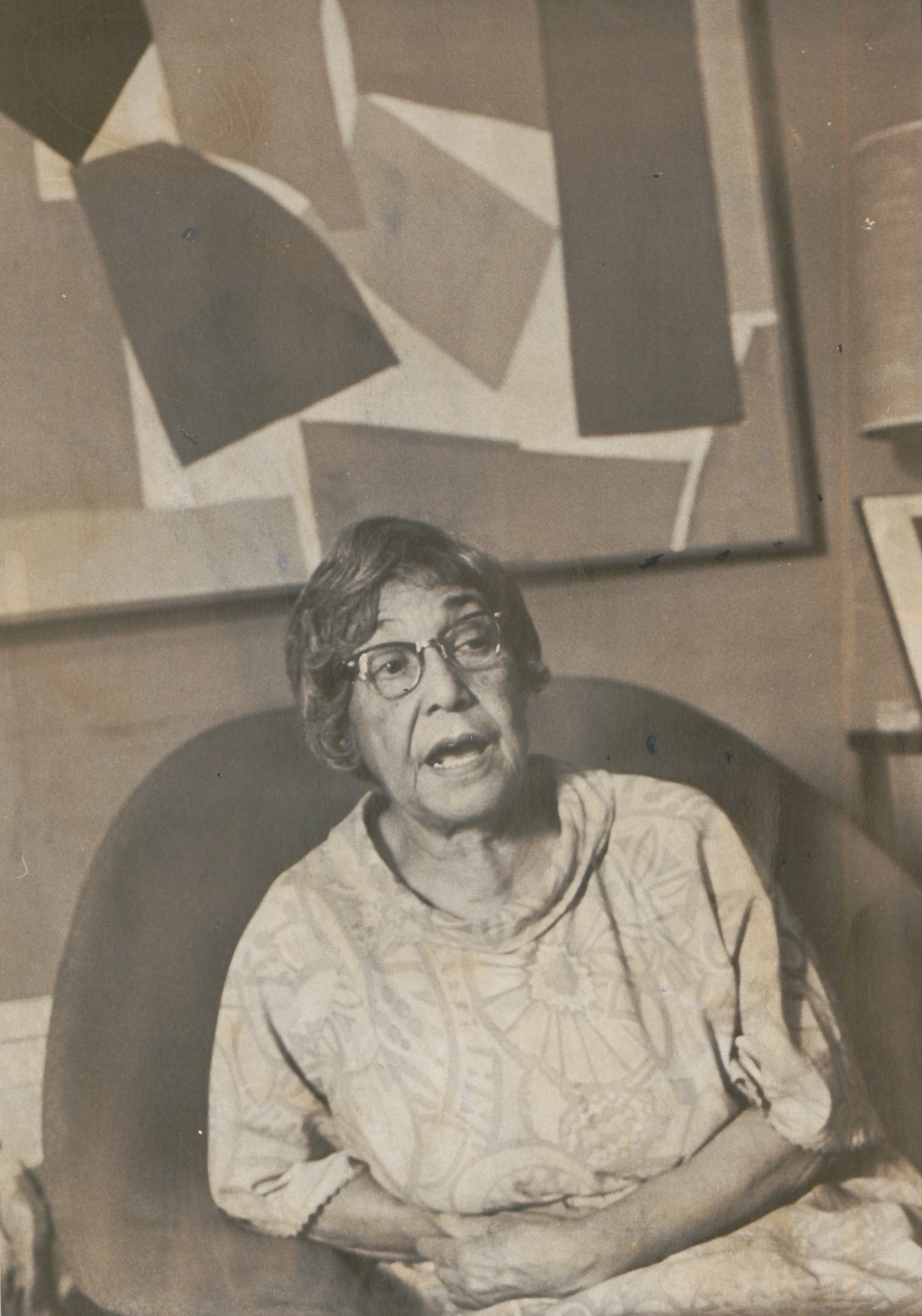

Alma Thomas, the African-American abstract artist and the subject of a recent WETA Arts episode, had many fans in Washington, D.C., but was her biggest fan… the CIA?

Thomas lived a life of remarkable firsts -- she was first graduate of the first fine arts program at an HBCU, D.C.’s Howard University. She founded the first art gallery in a D.C. public school in 1938 during her tenure at Shaw Junior High.1 Her painting career, though, did not take off until her retirement in 1960. But when she did take off, she soared.

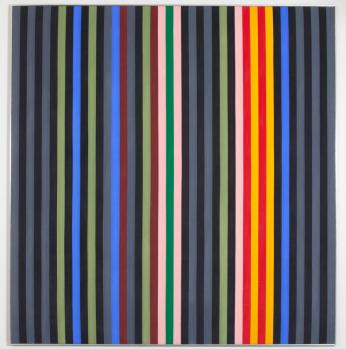

Almost all of Thomas’s later work is abstract; she was interested in the harmonies between colors, in the simplicity of patterns and shapes on canvas. She gravitated toward radiant rows of vivid color. Her abstractions were an attempt to communicate her inner experience and her impressions of the world around her. The concepts for her abstractions came from her experiences in nature (the holly bush in her front yard, for example) and from historical events (particularly advancements in space travel).2 In 1972, at age 81, Thomas became the first black woman with a solo show at the Whitney Museum in New York.

She was embraced by the Washington Color School, a movement of abstract artists who championed the power of abstract combinations of striking color; a sort of offshoot of Abstract Impressionism. DCist describes the Color School as Washington’s first art movement,3 and it remains one of the only distinctive art movements to come out of the District.

So how did this D.C. art movement get so much traction? Well, it may have happened naturally... but it also could have been helped by the Cold War. That’s because following World War II, modern art emerged as a powerful tool in the fight against the spread of Communism.

In 1946, the State Department purchased seventy-nine modern art paintings and toured them in a traveling exhibition titled “Advancing American Art.”4 Historian Lucie Levine writes that “Art stood out as a line of national defense, because it could,” in the words of former president of MoMA John Hay Whitney, “educate, inspire, and strengthen the hearts and wills of free men.” Modern art was supposed to show American freedom of expression and debunk Soviet claims that America was culturally barren.5

“Advancing American Art” was brought home in 1947, but the newly created CIA quickly picked up the mantel of American art promoter. Over the next two decades, the CIA – which took a special interest in abstract works of American Expressionism – worked with established arts foundations, artists groups and art museums (notably the Museum of Modern Art in New York City) to prepare special exhibitions, events and collections all over the world.6 The shows featured the work of Jackson Pollock and Willem De Kooning, among others.7

One major initiative was “The New American Painting,” which visited almost all major Western European cities in 1958-59. Art historian Jennifer Dasal writes, the tour "was strategic, a way to cement alliances among like-minded Cold Warriors and to promote the much-lauded cultural preeminence of the United States for the first time in history.”8

Notably, the artists, whose political ideologies usually stood in opposition to the CIA’s, were often kept in the dark about the CIA’s role in promoting their work. As former operative Donald Jameson observed, many “were people who had very little respect for the government in particular and certainly none for the CIA.”9 The agency employed a strategy called ‘the long-leash policy,’ wherein CIA operatives maintained two or three degrees of separation from the artists. Much of the Agency’s art promotion work was done through a new group it covertly helped create in 1950 (and helped fund for years) called the Congress for Cultural Freedom.10 The CCF held art exhibitions, organized international conferences, and sponsored public shows and performances for musicians and artists across the world.

In 1966 the operation became public when CCF Director Minoo Masani, announced that the organization had been the unwitting recipient of CIA funding. “We are annoyed that this trick should have been played us,” he said. The group stopped receiving CIA funding in January 1966 due to “suspicions… raised from where the funds were coming."11

The revelation didn’t stop the CIA’s interest in abstract painting – and the Washington Color School in particular – however.

Enter Vincent Melzac.

Melzac, described by eminent art critic Clement Greenberg as “the only art collector I know with guts,” was also the director of the Corcoran Gallery,12 an Arabian racehorse and catfish breeder, and a beauty school tycoon.13 In Melzac’s Washington Post obituary recalled, “the most celebrated incident of his tenure [at the Corcoran] was a fistfight he had with former gallery director Gene Baro” at a black-tie gala in 1971.14 As Roy Slade, who succeeded Baro as Corcoran director, remembered: “I looked behind me to see Gene Baro, blood streaming from his eye on to his white tuxedo shirt. Melzac was storming off with his wife. Gene stammered, ‘I think Melzac has gone to get a gun. I am going to lock myself in my office.’”15

While known for his “swashbuckling” personality, Melzac had very refined tastes when it came to art. He developed personal relationships with Alma Thomas and her Washington Color School contemporaries. As American University professor Ben Summerford put it, “He had a sincere belief in the avant-garde, in the work of his own time and in the freedom of expression demanded by artists.”16

Melzac purchased many Washington Color School works and began loaning parts of his collection to the CIA in 1968. According to the declassified CIA document “Paintings Loaned to CIA From The Vincent Melzac Collection,” the CIA borrowed three Alma Thomas paintings: “For Vincent” valued at $10,000, “Mars Reflection” valued at $15,000, and “Wind Dancing With Spring Flowers” valued at $10,000. Also on the receipt are two paintings by Norman Bluhm, six by Thomas Downing, five by Howard Mehring, one by Gene Davis, one by Robert Newman, and two by Morris Louis.17 The Agency later purchased some of the paintings from Melzac, who was awarded the Agency Seal Medallion in 1982 in recognition for his support of the CIA.18

For years, very little information was made public about the paintings that Melzac sold or loaned to the Agency.19 In 2009, Oregon artist Joby Barron submitted a series of FOIA requests to the CIA, asking for photos of the Melzac Collection and information about its acquisition. Those requests were repeatedly denied, which fed the curiosity about the collection from contemporary artists and art critics.20

In recent years, it seems that the CIA has been a bit more accommodating. In 2015, DC-based artist Barbara Januszkiewicz was allowed to film the painting for a documentary about the Washington Color School, and in 2016 Hyperallergic art critic Carey Dunne was permitted to tour the collection (with Agency chaperones, of course).21

The CIA even describes the collection – briefly – on its website:

“Every day, Agency employees walk past several abstract paintings that hang throughout the Headquarters buildings. These 29 paintings do not just break up the acres of wall space. They represent an elemental approach to art, a swashbuckling donor, and a connection to the architecture of the OHB.

"The way the eye perceives color and pattern were the subjects of Norman Bluhm, Gene Davis, Howard Mehring, Kenneth Noland, Thomas Downing, Alma Thomas, and the other artists of the Washington Color School. Their patron — and the donor of this collection to the Agency, the late Vincent Melzac — was a larger-than-life figure."22

So, now that the Cold War is over, is the collection at Langley solely there to beautify the space and serve as a tribute to a friend of the CIA? Or, does abstract expressionism still have a role to play in the mission of the CIA?

According to former CIA Museum director Carol Reams, it’s the latter. “[The paintings] are used for training purposes. We’ll have some of our guys and gals come down here and do a critical analysis of the paintings. Say you’ve got to analyze this big, heavy duty ISIL problem over here — maybe if you come look at the painting, it’ll help you think about how to solve the ISIL problem creatively.”23

Alma Thomas, Washington’s revolutionary Black artist, is now used to help train CIA operatives – does it get any more D.C. than that?

Footnotes

- 1 Forgey, Benjamin. “Alma W. Thomas Dies; Famed District Painter.” Evening Star, February 25, 1978. Access World News – Historical and Current.

- 2

Greenberger, Alex. “How Alma Thomas’s Radiant Paintings Plotted a New Course for Abstraction.” ARTnews.Com (blog), July 23, 2021.

- 3

Goss, Heather. “Discover Washington’s First Art Movement.” DCist (blog), April 11, 2007.

- 4

Halley, Catherine. “Was Modern Art Really a CIA Psy-Op?” JSTOR Daily, April 1, 2020.

- 5

Halley, Catherine. “Was Modern Art Really a CIA Psy-Op?” JSTOR Daily, April 1, 2020.

- 6

Dasal, Jennifer. “How MoMA and the CIA Conspired to Use Unwitting Artists to Promote American Propaganda During the Cold War.” Artnet News, September 24, 2020.

- 7

Romm, Jake. “CIA Art Collection: A Guide to the CIA’s Favorite Artists.” FORMAT, December 16, 2022.

- 8

Dasal, Jennifer. “How MoMA and the CIA Conspired to Use Unwitting Artists to Promote American Propaganda During the Cold War.” Artnet News, September 24, 2020.

- 9

Dasal, Jennifer. “How MoMA and the CIA Conspired to Use Unwitting Artists to Promote American Propaganda During the Cold War.” Artnet News, September 24, 2020.

- 10

Dasal, Jennifer. “How MoMA and the CIA Conspired to Use Unwitting Artists to Promote American Propaganda During the Cold War.” Artnet News, September 24, 2020.

- 11 The New York Times. “C.I.A. Tie Confirmed By Cultural Group.” May 10, 1967. Times Machine.

- 12

“George Bush Bust - CIA.” Accessed April 30, 2023.

- 13

K. Thompson. “Historical Highlight: Swashbuckling Collector Vincent Melzac.” From the Fort Wayne Museum of Art, November 20, 2019.

- 14

Washington Post. “Ex-Corcoran Gallery Chief Vincent Melzac Dies At 75.” Accessed May 2, 2023.

- 15 Roy Slade (2008) "Fisticuffs", Roy Slade's Artworld.

- 16

K. Thompson. “Historical Highlight: Swashbuckling Collector Vincent Melzac.” From the Fort Wayne Museum of Art, November 20, 2019.

- 17

“Paintings Loaned To CIA From The Vincent Melzac Collection.” CIA, September 2, 1982. General CIA Records.

- 18

CIA.gov. “Melzac Art Collection - CIA.” Accessed March 20, 2023.

- 19

One exception came in 2007, when Guggenheim Fellowship-winning photographer Taryn Simon gained access to the halls of the Langley headquarters and made a photograph of the Washington Color School artworks as a part of her series “An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar.”

- 20

Dunne, Carey. “A Visit to the CIA’s ‘Secret’ Abstract Art Collection.” Hyperallergic, October 20, 2016.

- 21

Dunne, Carey. “A Visit to the CIA’s ‘Secret’ Abstract Art Collection.” Hyperallergic, October 20, 2016.

- 22

CIA.gov. “Melzac Art Collection - CIA.” Accessed March 20, 2023.

- 23

Dunne, Carey. “A Visit to the CIA’s ‘Secret’ Abstract Art Collection.” Hyperallergic, October 20, 2016.

![Art collector Vincent Melzac [Reprinted with permission of the DC Public Library, Star Collection ©Washington Post]](/sites/default/files/styles/embed/public/2023-07/_Star_Bio_Vincent_Melzac0004.jpg?h=d7ae9c5f&itok=_W1hQ8EH)

![Art collector Vincent Melzac [Reprinted with permission of the DC Public Library, Star Collection ©Washington Post]](/sites/default/files/2023-07/_Star_Bio_Vincent_Melzac0004.jpg)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)