How a Taxidermist Helped Create the National Zoo and Save the Buffalo From Extinction

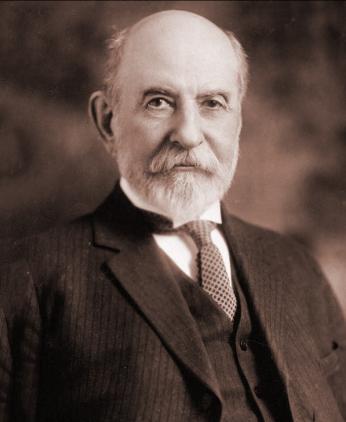

If you were a western settler in the 1870s looking for a home where the buffalo roamed, you might have had a hard time finding one. Homes on the range saw ever-dwindling numbers of buffalo (officially known as American bison), due to systematic campaigns of extermination that targeted not only bison, but gray wolves and cougars as well. Enter William Temple Hornaday, a hunter and taxidermist who witnessed the near extinction of the bison and decided that “preservation . . . is an imperative duty, for otherwise it will be too late.”1

In the present day, many endeavor to plan and implement beneficial conservation programs, but in the 1880s, there was no such respect for nature. The early conservation movement was a reaction to the country’s ruthless exploitation and destruction of natural resources. For reasons ranging from commercial exploitation to irrational hysteria, Americans appeared bent on attempting to dominate nature, with scant notion of the ecological consequences that extinction could entail.2

Instead of just working behind-the-scenes at museums as a taxidermist, Hornaday traveled on expeditions to Latin America and Asia to hunt wild animals for museum collections.3

In 1882, he was appointed Chief Taxidermist at the Smithsonian’s US National Museum (today the Arts and Industries Building on the National Mall).4

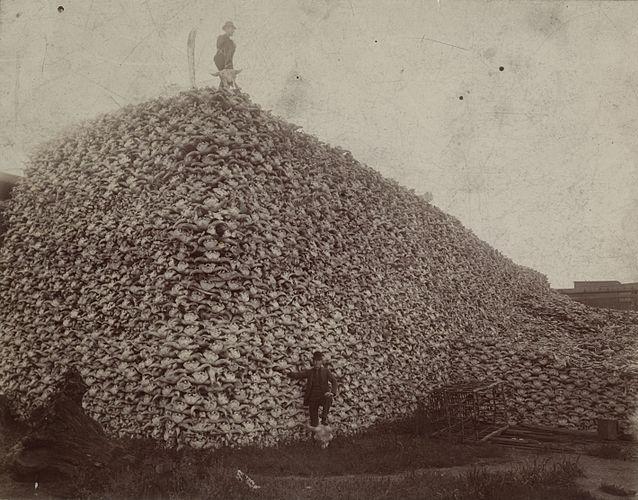

In 1886, the Smithsonian sent Hornaday to Montana to collect bison specimens for the museum’s collection. The museum wanted to display bison so Americans would remember the animal after its extinction, which was expected to be just around the corner.5 The bison was indeed on the very brink of extinction due to a growing market demand for hides and bones. However, and most sinister of all, bison were also killed en masse as part of a genocidal campaign by the U.S. government to deprive Native Americans of their food source, spiritual culture and autonomy, which the bison symbolized.6 This was a time when bison were shot from the windows of moving trains by passengers for sport.7 A time when so many bison were killed that mountains of skulls could be built. Native Americans had been hunting bison for millennia, but their lives depended on these animals. Not only did they hunt sustainably, but they didn’t leave any part of the animal go to waste. In contrast, many Americans shot bison and simply left them to rot where they died, taking only their hides, or nothing at all. They died not for the survival of their hunters, but for economic exploitation, and in many instances the perverse pleasure that casual brutality brought to their killers.

At the beginning of the 19th century, there were an estimated 30 million buffalo roaming North America. Herds were so huge that they could cover multiple square miles at once. After the arrival of the railroad, trains had to stop for hours to let herds pass over the tracks. The population was thought to be infinite by both white settlers and Native Americans alike. But by 1886, after decades of reckless slaughter, there could have been as few as 541.8

After reaching out to contacts across the country to figure out how many wild bison were left, Hornaday was stunned when his contacts remarked that they barely knew of any. During his 1886 expedition to Montana, where some of the last bison still roamed wild, he saw with his own eyes the true scale of the species’ destruction.9 Instead of the mega-herds that once covered the Great Plains, he was greeted by the bones of countless animals left to rot by trigger-happy Americans with no legal or moral inhibitions. Hornaday wrote “I received a severe shock, as if by a blow on the head from a well-directed mallet. I awoke, dazed and stunned, to a sudden realization of the fact that the buffalo hide-hunters of the United States had practically finished their work.”10

It is this profound discovery that began Hornaday’s transformation from hunter to conservationist. He was outraged by America’s wholesale destruction of an entire species and believed that the bison would go extinct without government intervention.

“In a very few years, not even a bleaching bone will remain above ground to tell the story of the millions that have been utterly destroyed by the senseless, heartless, and wasteful greed of man.”11

Although he still shot and harvested bison for the National Museum, he brought one calf alive back to Washington. He named it Sandy and nurtured him past infancy. Sandy died later that year. Hornaday was heartbroken by his death, and it’s possible he may have been inspired in part by this small tragedy to create the National Zoo, to preserve the little calf’s legacy, and that of the untold millions of his kind slaughtered by America’s recklessness.12

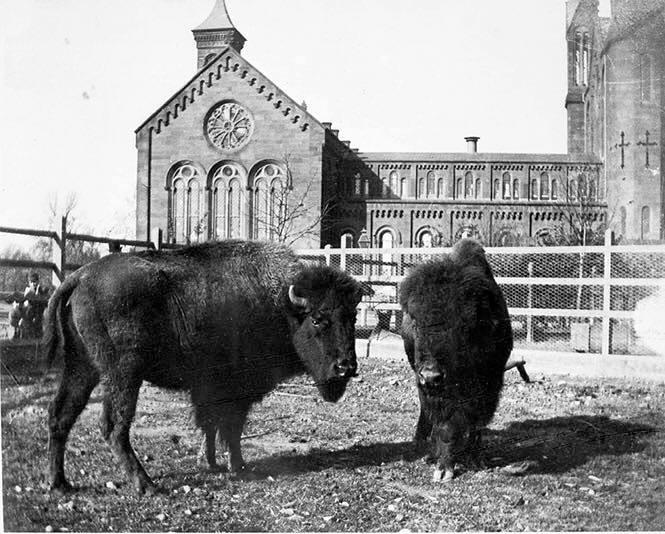

Hornaday wrote a letter to the Smithsonian, “it now seems necessary for us to assume the responsibility of forming and preserving a herd of live buffaloes which may, in a small measure, atone for the national disgrace that attaches to the heartless and senseless extermination of the species in a wild state.” He wasn’t satisfied with the numbers of bison kept by private owners, because of the chance of crossbreeding with domestic cattle. He wrote, “Is it not only desirable but imperative that we should have a herd fit to be shown as one belonging to the National Government?” Hornaday later returned to Montana and captured live adults to bring to Washington.13, 14

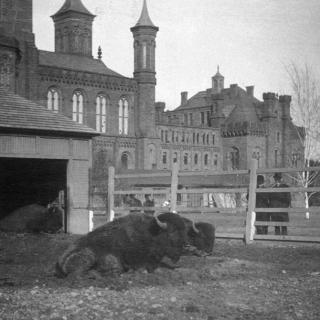

Hornaday’s change of heart led to the establishment of the National Museum's Department of Living Animals, a three-fold effort to save America’s vanishing wildlife from extinction. The Montana-caught bison were displayed in a pen on the National Mall, behind the Smithsonian Castle. One purpose of this display was to inspire appreciation for animals as charismatic as the bison, and to raise interest in the idea of saving them. A second purpose was to begin a captive breeding population, from which offspring could eventually be released to the wild and repopulate the species’ historic range. Curiously, a third purpose of keeping captive bison was to supply taxidermied specimens to the National Museum.15

Hornaday spent the rest of the 1880s spreading the message of the bison’s impending extinction and arguing for the species’ protection. In 1889, he published The Extermination of the American Bison, a landmark book illustrating the story of the bison from before the arrival of Europeans to their plight as a species guaranteed to go extinct without human intervention. Hornaday’s book argued for the protection of small remaining wild populations, like one that existed in the newly formed Yellowstone National Park.16

The Department of Living Animals, curated by Hornaday, grew to accommodate fifteen North American species in total, including badgers, bears, lynxes, and prairie dogs. They were a big hit, with several thousand people a day coming to admire this odd little collection of America’s natural marvels. Yet, his ambitions to conserve America’s vanishing wildlife extended beyond activism and a meager public exhibit in an area already overwhelmed with national landmarks and symbolism.

Hornaday lobbied Congress for the creation of a zoo dedicated to the conservation of endangered North American mammals. On March 2, 1889, he got his wish. President Grover Cleveland signed an act of Congress declaring the creation of the National Zoological Park, for “the advancement of science and the instruction and recreation of the people.” Hornaday’s vision was now set in legal stone, but actual stones needed to be turned for the National Zoo to fulfill its promise.

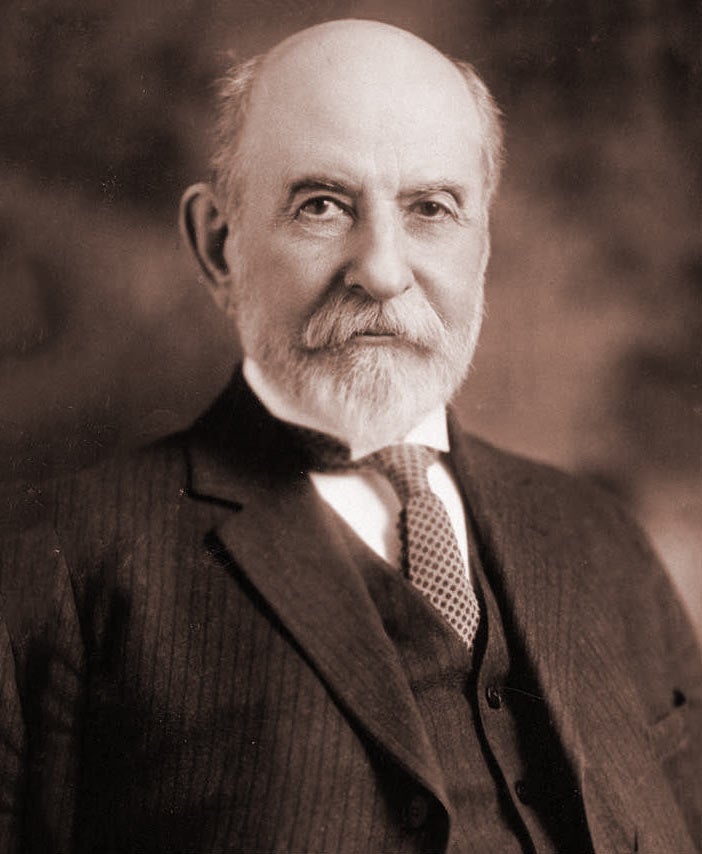

In 1889, the National Zoo was still just a menagerie on the National Mall. Overcrowding of both animals and visitors was an issue. New space was needed to accommodate the rapidly growing collection and throngs of visitors.17 Hornaday teamed up with Samuel Pierpont Langley, the new secretary of the Smithsonian. Today, Langley is best remembered for his pioneering (if not always successful) aviation work and inventions.

Hornaday was allocated $92,000 of federal funds to purchase land and was appointed as the National Zoo’s first director.18 He and Langley selected Rock Creek Park as the home for the nation’s zoo. Established by Congress in 1890, this newly designated national park protected woods, streams and slopes in the Rock Creek Valley.19 In 1890, Congress established the Zoo as a bureau under the Smithsonian Institution. It seemed like everything was falling into place. But one big question remained. Who would build it?

Enter Frederick Law Olmsted, widely considered the father of American landscape architecture. By 1889 he had already designed universal landmarks like Central Park in New York City. The trio drew up plans for a 163-acre zoo, which Hornaday envisioned with large, naturalistic enclosures in tune with the surrounding landscape, educating guests on the connection between animals and their habitats.20 This was a progressive idea for the time, when even the biggest zoos comprised iron-bar cages and concrete floors.21 Olmsted pictured a park-like atmosphere with a broad path sloping west to east. Today, Olmsted Walk is still the main avenue for guests to travel through the Zoo.22

Soon, however, the relationship between Langley and Hornaday began to deteriorate. Notorious for his rigid management style, Langley demoted Hornaday by devising an organizational structure that left him out of the Zoo’s top management decisions. It is possible that Langley, being 20 years older than Hornaday, just wanted to put the younger man in his place. But Hornaday wasn’t easy to work with either. While passionate about his work, by many accounts, he was arrogant and temperamental. Outraged by Langley’s management, Hornaday resigned from the Smithsonian in 1890. Langley remained with the National Zoo until 1906.23

The National Zoo officially opened in 1891. About 185 animals from the growing Department of Living Animals became its first residents, along with two elephants donated from a circus. A log cabin was built to house bison and elk, which roamed a fenced yard. The Animal House became the first permanent building when it opened in 1892. It was replaced by the still-existing Reptile House in 1931.

Over the next century, the National Zoo expanded into the institution it remains today, becoming home to stars like Smokey Bear, Ham the chimpanzee (the first great ape to go into space), and Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing, the giant pandas gifted to the US by China after President Richard Nixon’s visit to the country in 1972.24

Today, despite more than 130 years of changes, the Zoo’s original mission of wildlife conservation has remained set in stone. Exhibits like Amazonia and Asia Trails educate guests about the interdependence between animals and their environment by immersing them in convincing recreations of wild ecosystems and using interpretive signage to illustrate the existential challenges facing Earth’s biodiversity. The Smithsonian even opened a secondary facility near Front Royal, Virginia, exclusively devoted to breeding endangered species and training future conservationists.25 Hornaday would be proud.

Today, two female bison reside at the National Zoo in an exhibit near the pandas and cheetahs.26 They might get overshadowed by their more famous neighbors, but they are a reminder of William Hornaday’s evolution – from taxidermist to conservationist – and the invaluable role he and the National Zoo played in saving an American icon.

So what happened to Hornaday after he left the National Zoo in 1890? Though cut out from the National Zoo’s future, he continued his work in conservation. In 1896, he became director of the Bronx Zoo, created by the New York Zoological Society, which became the most important facility for bison conservation among American zoos.27

His career was not without controversy, however. Hornaday’s legacy was tarnished by his support of eugenicist Madison Grant, and his exhibition of a Congolese pygmy at the Bronx Zoo in 1906. The practice of human zoos was common in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Hornaday put the Congolese man, named Ota Benga, on display in the Monkey House after he piqued the public’s curiosity while he spent time on zoo grounds, caring for animals without getting paid.28 Regrettably, it also must be remembered that Hornaday killed many endangered animals for his taxidermy displays, although he viewed this as necessary to bring the American public’s attention to their existence. He remained with the Bronx Zoo until the 1920s and died in 1937.29

As for the bison, which Hornaday had sought to taxidermy and then save – they would recover. In 1907, the Bronx Zoo began reintroducing captive bison into national parks and reserves in their native range. Today, tens of thousands of wild bison roam America’s wilderness today, and their conservation is primarily managed by the US Department of the Interior, which strives to prevent future population crashes. While they may never return to the vast mega-herds that shaped the land and cultures around them, the bison’s future as a species seems secure.30

Footnotes

- 1

Hornaday, William T. Our Vanishing Wild Life: Its Extermination and Preservation. New York: New York Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913.

- 2

Baron, David. The Beast in the Garden: The True Story of a Predator’s Deadly Return to Suburban America: Baron, David: 9780393326345: Amazon.Com: Books. W. W. Norton & Company, 2003.

- 3

Hornaday, William T. Two Years in the Jungle : The Experiences of a Hunter and Naturalist in India, Ceylon, the Malay Peninsula and Borneo. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1885.

- 4

“William Temple Hornaday: Saving the American Bison.” Smithsonian Institution Archives, September 14, 2012.

- 5

Montana River Action. “Musselshell - An Endangered River.” Archive, July 15, 2009.

- 6

Ozark Bisons. “About the Majestic American Bison: Genocide and Recovery.” Accessed October 13, 2023.

- 7

King, Gilbert. “Where the Buffalo No Longer Roamed | The Transcontinental Railroad Connected East and West--and Accelerated the Destruction of What Had Been in the Center of North America.” Smithsonian Magazine, July 17, 2012.

- 8

Ozark Bisons. “About the Majestic American Bison: Genocide and Recovery.” Accessed October 13, 2023.

- 9

Montana River Action. “Musselshell - An Endangered River.” Archive, July 15, 2009.

- 10 Bechtel, Stefan. Mr. Hornaday’s War: How a Peculiar Victorian Zookeeper Waged a Lonely Crusade for Wildlife That Changed the World. Beacon Press, 2012.

- 11

Sheu, Sherri. “Reconstructing William Temple Hornaday’s 1888 Extermination Series.” Smithsonian Institution Archives, March 2, 2017.

- 12

“W.T. Hornaday.” Accessed October 27, 2023.

- 13

Google Arts & Culture. “Hornaday Letter to Goode 2 Dec1887 - Page 1 - William Temple Hornaday.” Accessed October 27, 2023.

- 14

“William Temple Hornaday: Saving the American Bison.” Smithsonian Institution Archives, September 14, 2012.

- 15

Robinson, Michael. “William Temple Hornaday, Visionary of the National Zoo - National Zoo| FONZ.” Archive. Friends of the National Zoo, February 1989.

- 16

Hornaday, William T. The Extermination of the American Bison. Washington D.C.: Washington Government Printing Office, 1889.

- 17

Fthenakis, Lisa. “Animals Behind the Castle: The Department of Living Animals.” Smithsonian Institution Archives, July 18, 2017.

- 18

Smithsonian’s National Zoo. “About the Zoo: History,” April 20, 2016.

- 19

National Park Police. “History & Culture - Rock Creek Park (U.S. National Park Service).” Accessed October 17, 2023.

- 20

“Smithsonian National Zoological Park | TCLF.” Accessed October 24, 2023.

- 21 Croke, Vicki. The Modern Ark: The Story of Zoos: Past, Present & Future. Diane Pub Co, 1997.

- 22

“Smithsonian National Zoological Park | TCLF.” Accessed October 24, 2023.

- 23

Smithsonian’s National Zoo. “American Bison,” April 20, 2016.

- 24

“National Zoological Park.” Smithsonian Institution Archives, April 18, 2011.

- 25

Smithsonian’s National Zoo. “About the Zoo: History,” April 20, 2016.

- 26

Smithsonian’s National Zoo. “American Bison,” April 20, 2016.

- 27

“About Hornaday · Hornaday Wildlife Conservation Scrapbooks.” Accessed October 24, 2023.

- 28

Human Zoos: America’s Forgotten History of Scientific Racism. Documentary. Discovery Science, 2019.

- 29

“About Hornaday · Hornaday Wildlife Conservation Scrapbooks.” Accessed October 24, 2023.

- 30

“Protecting Bison - Bison (U.S. National Park Service).” Accessed October 24, 2023.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)