The 11th and a Half President? The Myth of David Rice Atchison

Between 1821 and 1933, Inauguration Day was not January 20, but March 4. More than two dozen presidents happily took the Oath of Office as prescribed by the Constitution on this day—but when March 4, fell on a Sunday, things got complicated.

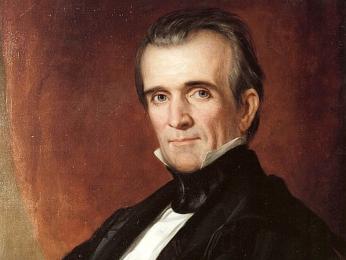

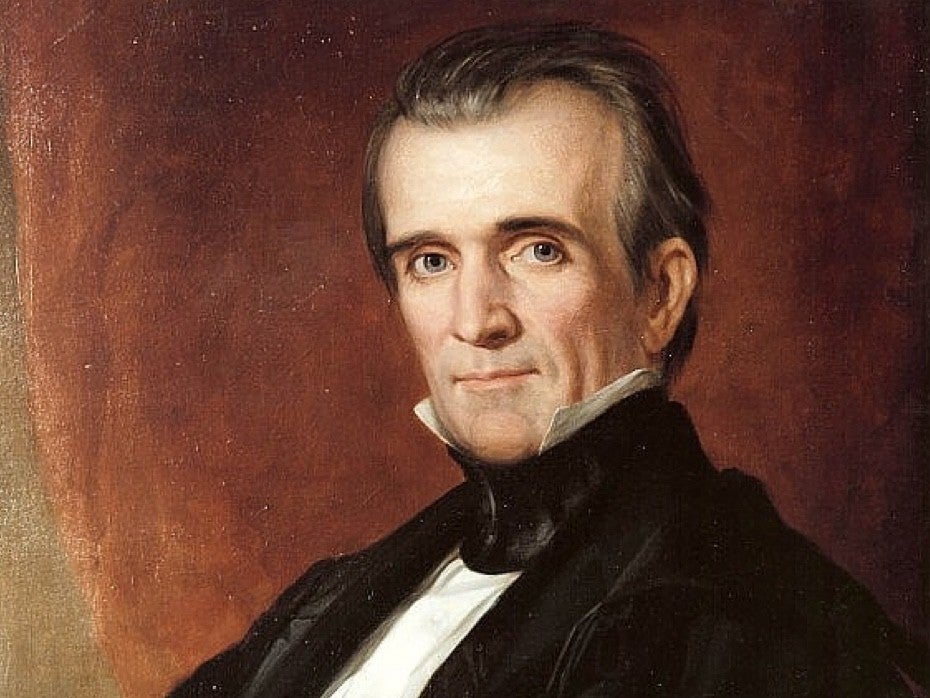

Such was the case in 1849. At 6:30 in the morning of Sunday, March 4, outgoing president James Polk wrote in his diary that he had “closed my official term as President of the U.S.” (though he was still technically in power until noon).1

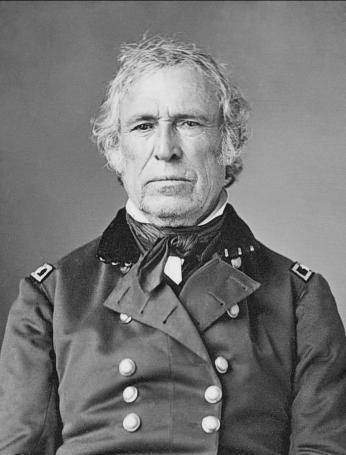

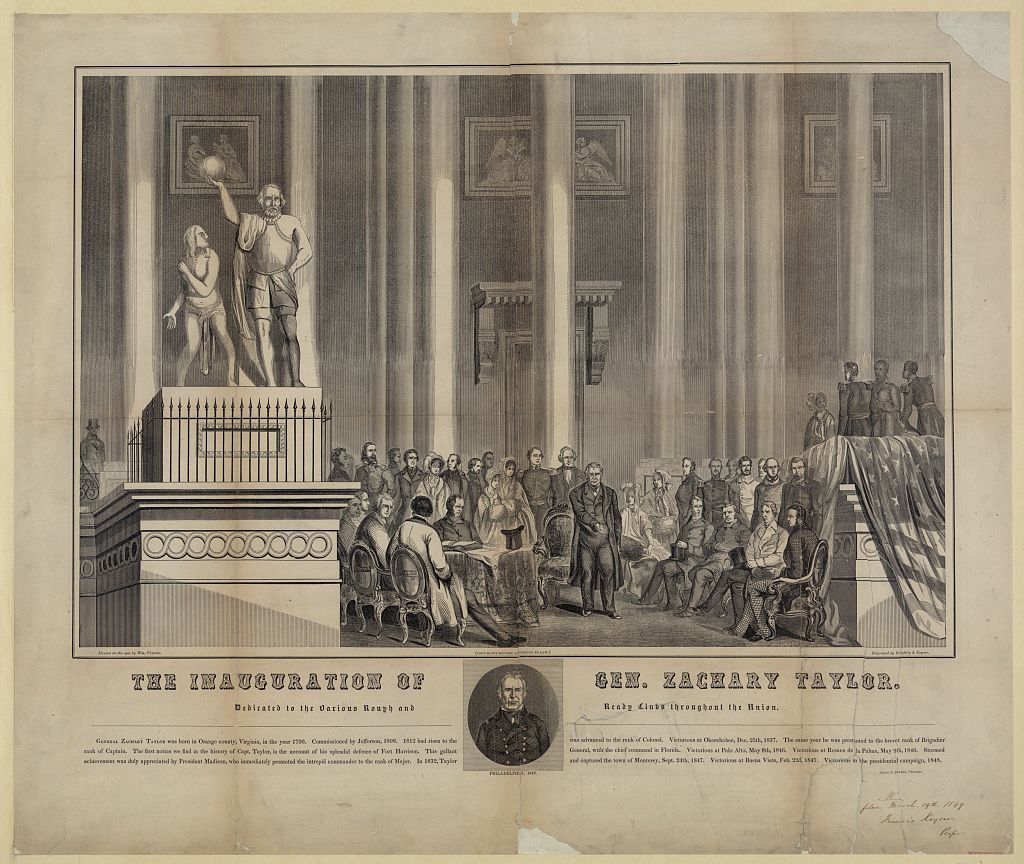

Ordinarily at that time, the next administration would be sworn in, and the transfer of power would shuffle along without a hitch. But President Elect Zachary Taylor, “a devout Episcopalian,” refused to conduct the ceremony on the Sabbath, a day on which “business and pleasure [are] improper.”2 3 He would wait until noon on Monday to take his oath.

With Polk out of office and Taylor waiting to be sworn in, that left twenty-four hours without a president to preside over the nation.

So who was president from noon on March 4, 1849, until noon on March 5?

Enter the myth of the eleventh-and-a-half President.

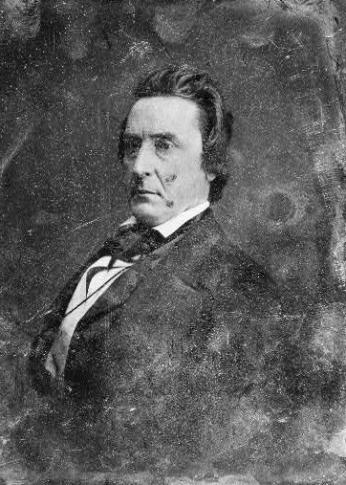

In 1849, David Rice Atchison was a senator from Missouri and president pro tempore of the Senate (a high-ranking senator of the majority party who presides over the US Senate in the absence of the vice president). He was described as “a man of imposing presence, six feet, two inches high. He was the soul of honor, a fine conversationalist, and possessed a great memory. As a man he was plain, jovial, and simple in his tastes.”4 He was “popular with his Senate colleagues,” who elected him pro tempore thirteen times.

Atchison was also deeply pro-slavery, sometimes to deadly effect. He formed part of the influential F Street Mess that championed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, allowing slavery to expand into western states.5 He was a rhetorical leader of the Border Ruffians, who crossed into Kansas in 1855 to elect a pro-slavery legislature at gunpoint. During one speech, Atchison told his followers to “give a horse thief, robber, or homicide a fair trial, but to hang a negro thief or Abolitionist, without judge or jury.”6

Atchison and his politics have since faded into relative public obscurity. His name is most often connected with his claim—reproduced on his tombstone—to be America’s only interregnum President.

Zachary Taylor was confident in delaying his inauguration to observe the Christian Sabbath. He took his precedent from James Monroe, the first president to encounter the situation (the same president, in fact, that informally set March 4 as inauguration day). Monroe looked to the Supreme Court for guidance. Chief Justice John Marshall wrote back:

There is an obvious propriety in taking the oath as soon as it can conveniently be taken… But some interval is inevitable… [and may] be unavoidably prolonged. If any circumstances should render it unfit to take the oath on the 4th of March, and the public business would sustain no injury by its being deferred… no impropriety is perceived in deferring it till the 5th. 7

John Quincy Adams noted in his diary that Sunday became “a sort of interregnum during which there was no [constitutionally] qualified person to act as President.”8 Of course, this was fairly harmless because Monroe was an incumbent president—both outgoing and incoming administrations were the same. Not so in 1849.

The Succession Act of 1792 provided, in the “removal, death, resignation, or inability” of both the President and Vice-President to govern, the responsibility fell to the president pro tempore of the Senate.9 With Polk’s term definitely over on March 4, and Taylor definitely without an inauguration, when people looked for an acting president, Atchison was next down the line.

But what did his twenty-four hour presidency look like? Fairly boring. Atchison told a reporter how he spent his administration: “I went to bed… There had been two or three busy nights finishing up the work of the Senate, and I slept most of that Sunday.”10

Despite no official government record mentioning Atchison ever assuming the office of President, he enjoyed joking about it later in life. Often he would call his the “honestest administration this country ever had.” He also recalled that a North Carolina senator woke him at three in the morning on March 5 and asked to be made Secretary of State. A few Democratic colleagues “playfully suggested” that he summon the army and prevent Taylor, a Whig, from assuming power.11

But Atchison himself maintained that he was never president in any meaningful capacity. In a letter, he wrote that he had “never for a moment acted as President” nor did he “ever consider that I was the legal President of the US.”12

Interestingly, in 1849, neither press nor public seemed concerned about an AWOL Commander in Chief. A few small articles from the time floated the idea of Atchison as an interim president, but none took the idea seriously. The National Intelligencer had to issue a statement that its characterization of Atchison as president “was of course intended for a jest” and clarified that at no point would he have been constitutionally qualified to assume the office.13

Only later—in the 1890s and 1900s—did the story of the eleventh-and-a-half President have a resurgence. Some journalists painted Atchison as a neglected historical figure “omitted by both the histories of the United States and the encyclopedias.”14 Many articles were wildly inaccurate. One article described Washington on the evening of March 4 as “a camp of violence” and that Atchison “sent to the White House for the seal… and signed two or three official papers as president.”15 In fact, by Atchison’s own admission, he was sound asleep in bed!

A 1908 article from the New York Tribune put the issue to rest for its readers this way: Atchison was qualified only “to succeed to the Presidency on the removal, death, resignation, or inability of the President and Vice-President. But on March 4, 1849, both a President and a Vice President were on hand, qualified to assume office.” 16

Of course, the majority of constitutional and legal scholars also disavow any claims that Atchison was legally or practically president in 1849. For one, he was only thirty-two years old in 1849, three years shy of qualifying for the presidency. For another, Atchison’s term also expired alongside Polk’s on March 4 when the Senate recessed for the final time.

Much of the debate lies in when a president becomes president. The Constitution requires the president to “swear or affirm” the Oath of Office. Tradition implies that one assumes the presidency after swearing the Oath of Office. (Though even that has been the cause of some confusion: the oath was misread during President Barack Obama’s inauguration, and he had to retake it correctly the next day. *Atchison never swore an oath.)

Modern scholars say that while Taylor had not yet been sworn in, that didn’t constitute an inability to carry out presidential duties: “If sudden emergency had arisen on that Sunday afternoon or Monday morning” it wouldn’t have “devolved upon the president pro tempore [Atchison]… to act as President of the United States.”17 However, politicians of the 1850s might have disagreed. Polk did not begin to call Taylor President until after he had been sworn in. The Congressional Globe also wrote that at 12:30, “the President elect, Gen. Zachary Taylor, supported by the Ex-President, the Hon. Kames K. Polk, entered.” Not a president to be seen!

Nonetheless, legal historians make a distinction between the assumption and execution of the office of president. The Constitution requires that the oath be taken “before he enter upon the execution of his office,” not necessarily before someone becomes president. The opposite interpretation (that Taylor wasn’t president until he took the oath on March 5) meant that Taylor could have been president until March 5, 1853, gaining a full extra day and delaying his successor’s term by the same amount. The long-term havoc these shifts could wreak on electoral calendars puts it “quite out of the question.”18

It is possible that Atchison may have been acting president for a few minutes. The first act of the newly convened Senate on March 5 was to swear Atchison in as pro tempore before attending to the presidential Oath of Office. Without Polk and with Taylor awaiting his Oath, Atchison briefly became the highest authority in the US. But by this logic, Vice President Milard Fillmore was also president for a few minutes, superseding Atchison as he was sworn in just before Zachary Taylor.

If that’s case, it looks as if Mr. Atchison may have to update his gravestone, and share that temporary President spotlight with Fillmore.

Of course, the problem of Inauguration Day falling on a Sunday continues to pop up. Seven presidents have dealt with inaugurations on the Sabbath: Monroe in 1821, Taylor in 1849, Hayes in 1877, then Wilson, Eisenhower, Reagan, and Obama. Due to a prickly election, Hayes was the first to opt for a private Oath of Office on March 3 (giving America, for one day, two presidents). Presidents following him have opted to take a private oath on Sunday, followed by a public ceremony the next day, Monday.

If anything, Atchison’s case is special because it is the only one with contentions, whether sincere or facetious. No one made a fuss about presidential successors in 1821, even as John Gailard of South Carolina served “continuously” as pro tempore with an absent Monroe. Neither did anyone raise the subject of a half-president when Woodrow Wilson delayed his inauguration in 1917.19

But we have some time before we have to worry about all of this again—the next time Inauguration Day falls on Sunday won’t be until January 20, 2041!

Footnotes

- 1

Senate Historical Office. “U.S. Senate: David Rice Atchison: (Not) President for a Day.” US Senate, November 13, 2020.

- 2

Bloom, Joseph H. 2003. “David Rice Atchison.” American History 37 (6): 18.

- 3

Willen, Sara. “President for a Day.” Shapell, January 21, 2013.

- 4 Bloom, Joseph H. 2003. “David Rice Atchison.” American History 37 (6): 18.

- 5 For a greater exploration of this topic, see The F Street Mess by Alice Elizabeth Malavasic.

- 6

Johannsen, Robert W. The Mississippi Valley Historical Review 48, no. 3 (1961): 524–26.

- 7

New-York tribune. (New York [N.Y.]), 10 Feb. 1908. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 8

Willen, Sara. “President for a Day.” Shapell, January 21, 2013.

- 9

Haynes, George H. “‘President of the United States for a Single Day.’” The American Historical Review 30, no. 2 (1925): 308–10.

- 10 Bloom, Joseph H. 2003. “David Rice Atchison.” American History 37 (6): 18.

- 11

Senate Historical Office. “U.S. Senate: David Rice Atchison: (Not) President for a Day.” US Senate, November 13, 2020.

- 12

Atchison to Joseph W. Howirth, n.d (post March 5, 1849). Shapell.

- 13

The Daily spy. [volume] (Worcester [Mass.]), 17 March 1849. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 14

The Mt. Sterling advocate. (Mt. Sterling, Ky.), 24 Sept. 1901. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 15

Pullman herald. (Pullman, W.T. [Wash.]), 28 Nov. 1896. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 16

New-York tribune. (New York [N.Y.]), 10 Feb. 1908. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 17

New-York tribune. (New York [N.Y.]), 10 Feb. 1908. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 18

Haynes, George H. “‘President of the United States for a Single Day.’” The American Historical Review 30, no. 2 (1925): 308–10.

- 19

Hylton, J. Gordon. “President for a Day – Marquette University Law School Faculty Blog.” Marquette University Law School, March 4, 2010.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)