The Great 1936 Flood of Great Falls... and Everywhere Else

Around 2 o’clock in the afternoon on March 19, 1936, President Franklin D. Roosevelt left the White House. His original plan for the day was to leave for his annual fishing trip to the Bahamas, but a more pressing matter had arisen in Washington D.C.. Accompanied by Secretary of War and the newly appointed chairman of the Flood Relief Committee, George Dern, the two drove towards the edge of the Potomac, where floodwaters were advancing on the capital city.1 The river had overflowed its banks and was pushing against hastily built barricades at the Munitions building and the Washington Monument. The Airfield, Tidal Basin, and the base of multiple monuments were already completely submerged.

The front page of The Evening Star laid bare the dire situation: “Peak of Flood to Hit D.C. at 6 P.M.; Chain Bridge Expected to Go Out.”2 Beneath the headline were photos and a dramatic account of Eva Dell Myers, a 50 year old widow who had been rescued from rising waters just outside of D.C. “Mrs. Myers’ home was swept several hundred feet down the Potomac. Her dog and chickens took refuge on the roof but were lost when a tree fell upon it.”3 Myers wasn’t the only flood victim. Up and down the river people rushed to rescue those who were stranded and tried to secure their homes against the ever-rising waters.

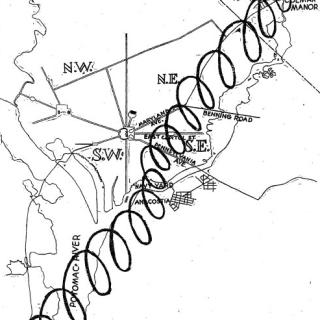

The scary scene in D.C. had been days in the making and was playing out across the Northeast United States. In quick succession, three torrential rainstorms came up from the Gulf of Mexico and worked their way up the coast, gaining strength at the Chesapeake Bay before making landfall.4 Natural protections against the water were filled from an unusual amount of rain combined with some remaining snowpacks in the mountains. By the time the third storm arrived on St. Patrick’s Day, “dry” land was saturated, and waterways were overflowing.5

Sixty miles up the Potomac, the town of Harpers Ferry, WV showed what could be in store for Washington. The rain and water runoff from the mountains caused the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers to rise. While the small town was no stranger to floods, it had never seen one as high as the one that was about to hit.6 The Bollman and Shenandoah bridges were torn from their foundations and swept away. Shops and houses were submerged. In total, the water rose 36 ½ feet. Pictures show the landscape flattened by water, with only the tops of buildings and the elevated railway tracks visible above the waterline.7 Perched on a hill overlooking Harpers Ferry, the St. Peters Roman Catholic Church was one of the few lucky buildings to escape the water.8 While Harpers Ferry had recovered from floods before, the extent of the damage coinciding with the Great Depression meant the town’s future was in significant danger.9

“CAPITAL FACES FLOOD” warned the front page of the Washington Times on March 18 as D.C. scrambled to prepare.10 Flood control specialists were called into the War Department to discuss what to do about the rising river. Some experts predicted it would be worse than the flood of 1889, which had destroyed a large section of the downtown.11 Engineers and members of the Civilian Conservation Corps got busy filling sandbags and moving dirt to make dikes to protect monuments and government buildings. As the workers prepared, papers published the damage that had already befallen cities along other rivers and up the Potomac. By 4pm on March 18 the waters had already risen 8ft and were still climbing. When the emergency walls were finished, all that was left to do was wait to see if they would hold.12

The next morning, the gauge on the Key Bridge recorded the water height as 17.4 ft above average, before it was completely submerged.13 The river had already claimed the tidal basin, airfield, navy yard, and sections of Georgetown. As the President began to drive around the city, the water had already made its way up 17th street and was running up against the dike.

As The Evening Star reported, the situation across the city was dire. “Three fire engines were pumping in the Navy Yard this afternoon in an almost vain effort to save the power plant from inundation,” read one story. Other accounts mentioned people evacuating, flood protections failing, and the efforts to save a man in a rowboat that got swept past Alexandria.14 There was one bit of good news: despite the odds and its submersion, the Chain bridge had managed to hold on, though it was severely damaged and had to be closed.15 Though chunks of the city being completely flooded, the worst seemed to have been averted.

The water slowly began to recede over the next few days, but not before it had claimed over 150 casualties across multiple states and left behind layers of mud as a reminder of how far the waters were able to reach.16 Johnstown, Pennsylvania resident Robert Boyle captured a scene that was playing out across several states. “The first thing to get the eye was the covering of thick mud that the city street cleaners were already attempting to clean up. It looked as though it would be just as easy to relay another hard surface over top of the thick muck after it dried as it would be to dig and shovel the streets and sidewalks back to normal.”17 In Harpers Ferry, the waters receded to reveal significant damage to the lower town and effectively ended the industrial and commercial future of the city.18 However, a few years later, Harpers Ferry would be established as a national monument, preserving it and its history. At Great Falls, the jagged stone walls of Mathers Gorge slowly became visible again as the water slowly drained from the gorge to reveal the familiar rocks.

When the water left D.C., the city began putting itself back together. Mud was scraped from the streets and rubble was collected and thrown back into the river.19 As the people cleaned and reconstructed, Congress got to work too. Coincidentally, a big issue of the past few decades had been flood control and debates about what the government's role should be to prevent flooding. Over the years a few bills had been passed but they either didn’t do enough or weren’t enforced.20, 21 However, when the waters started approaching Capitol Hill, it seemed to give Congress the push it needed to take action.

As one senator remarked as the waters were still rising outside, “By walking to the dome of the Capitol anyone of us may view the damage wrought by the flooded Potomac” and “...I am convinced that the time has come when we shall be guilty of criminal negligence if we do not take practical measures at once to protect the lives and property of the people whose destiny is so closely allied with proper flood-control projects.”22

Whether it was the moving words, the waters right outside their door, or just politics as usual Congress did take action a few months later, passing the Flood Control Act of 1936. The act recognized flood control as a national priority and allowed various government agencies to build flood prevention projects such as levies and floodwalls. The legislation has had its share of controversy over cost sharing and other issues, but still affects how flood control is managed today.23, 24, 25

As it goes with all natural disasters, life eventually returned to normal. On March 24, 1936, FDR finally left the White House to go to the Bahamas to enjoy a two week fishing trip.26 Meanwhile, work to rebuild damaged areas in and around D.C. continued. Today, the most prominent vestige of the 1936 flood is a wooden marker at Great Falls Park. Located in front of one of the observation decks, the beam shows the height of the Potomac’s waters during various flood years. At the very top, more than 10ft above the ground, it reads “1936.”27, 28

Footnotes

- 1

Evening Star. “Peak of Flood to Hit D.C. at 6 P.M.; Chain Bridge Expected to Go Out.” March 19, 1936. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1936-03-19/ed-1/seq-1/.

- 2

Evening Star. “Peak of Flood to Hit D.C. at 6 P.M.; Chain Bridge Expected to Go Out.” March 19, 1936. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1936-03-19/ed-1/seq-1/.

- 3

Evening Star. “Woman, 50, Saved After Roof Vigil” March 19, 1936. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1936-03-19/ed-1/seq-1/.

- 4

National Weather Service. “1936 Flood Retrospective.” NOAA’s National Weather Service. Accessed May 27, 2025. https://www.weather.gov/lwx/1936Flood.

- 5

National Weather Service. “1936 Flood Retrospective.” NOAA’s National Weather Service. Accessed May 27, 2025. https://www.weather.gov/lwx/1936Flood.

- 6

National Park Service. “Memorable Floods at Harpers Ferry - Harpers Ferry National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service),” April 10, 2015. https://www.nps.gov/hafe/learn/historyculture/memorable-floods-at-harpers-ferry.htm.

- 7

Oliver, Catherine. “Historic Floods Throughout the Years in Harpers Ferry | Harpers Ferry Park Association.” Harpers Ferry Park Association, September 12, 2018. https://www.harpersferryhistory.org/historic-floods-throughout-years-harpers-ferry.

- 8

National Weather Service. “1936harpersferry.Jpg (1200×818).” Accessed May 29, 2025. https://www.weather.gov/images/lwx/Hydrology/1936Flood/1936harpersferry.jpg.

- 9

Evening Star. “Great Falls Loses Its Identity as Flood Waters Rush Toward Sea.” March 19, 1936. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1936-03-19/ed-1/seq-11/

- 10

Washington Times. “Capital Faces Flood.” March 18, 1936. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026749/1936-03-18/ed-1/seq-1/.

- 11

Washington Times. “Capital Faces Flood.” March 18, 1936. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026749/1936-03-18/ed-1/seq-1/.

- 12

Evening star. “D.C. Flood Log.” March 19, 1936. https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn83045462/1936-03-19/ed-1/?sp=8&st=image&r=-0.338,0.002,1.783,0.705,0

- 13

Evening star. “D.C. Flood Log.” March 19, 1936. https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn83045462/1936-03-19/ed-1/?sp=8&st=image&r=-0.338,0.002,1.783,0.705,0

- 14

Evening Star. “Flood Bulletins.” March 19, 1936. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1936-03-19/ed-1/seq-1/.

- 15

ghostsofdc. “Where Washington’s Historic Chain Bridge Gets Its Name.” Ghosts of DC (blog), February 14, 2013. https://ghostsofdc.org/2013/02/14/called-chain-bridge/.

- 16

The Evening Star. “Rivers Go Higher With 153 Dead in U.S.” March 20, 1936. https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn83045462/1936-03-20/ed-1/?sp=1&st=image.

- 17

Heritage Johnstown. “1936 Flood Accounts.” Accessed May 27, 2025. https://www.heritagejohnstown.org/about-us/archives-research/collections/transcription-project/.

- 18

National Weather Service. “1936 Flood Retrospective.” NOAA’s National Weather Service. Accessed May 27, 2025. https://www.weather.gov/lwx/1936Flood.

- 19

Flood Special Pennsylvania 1936. Internet Archive, 1936. http://archive.org/details/FloodSpecialPennsylvania1936.

- 20

Arnold, Joseph. “The Evolution of the 1936 Flood Control Act.” Accessed May 29, 2025. https://www.publications.usace.army.mil/Portals/76/Publications/EngineerPamphlets/EP_870-1-29.pdf.

- 21

Other attempts at flood control bills include the Flood Control Act of 1917 and the Swamp Lands Act of 1849.

- 22

Congress.Gov. “Congressional Record.” Legislation. Accessed June 10, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/bound-congressional-record/1936/03/19.

- 23

Fema. “History of Levees.” Accessed June 10, 2025. https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-08/fema_history-of-levees_fact-sheet_0512.pdf.

- 24

Arnold, Joseph. “The Evolution of the 1936 Flood Control Act.” Accessed May 29, 2025. https://www.publications.usace.army.mil/Portals/76/Publications/EngineerPamphlets/EP_870-1-29.pdf.

- 25

As mentioned in “The Evolution of the 1936 Flood Control Act”, the bill stated that Flood Control should be a federal issue rather than a fully state issue, and allowed a significant number of flood control projects to begin. Some of these measures can be seen along rivers today and the policies put in place at the time still guide modern day flood control efforts.

- 26

Office of the Historian. “Franklin D. Roosevelt - Travels of the President - Travels - Department History - Office of the Historian.” Accessed May 28, 2025. https://history.state.gov/departmenthistory/travels/president/roosevelt-franklin-d.

- 27

National Park Service. “Floods - Great Falls Park (U.S. National Park Service),” December 6, 2023. https://www.nps.gov/grfa/learn/nature/floods.htm.

- 28

The Historical Marker Database. “Floods at Great Falls Historical Marker.” Accessed June 10, 2025. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=194509.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)