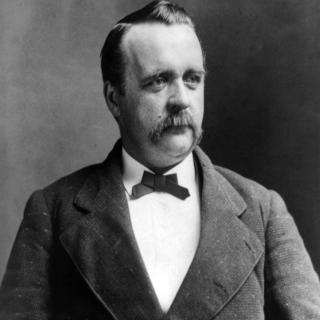

Edward Payson Weston: The Most Famous Athlete You’ve Never Heard Of

It was 1860 and Edward Payson Weston was a 21-year-old bookseller out for a meal with a friend named George B. Eddy. The two decided to make a bet that “if Abraham Lincoln were elected by the people, President of these United States, I [Weston] would agree to walk from Boston State House to the Capitol at Washington, D.C. (a distance of four hundred and seventy-eight miles), inside of ten consecutive days.”1 Eddy agreed to do the same if Lincoln were not elected.

When this bet was made, both men thought of it as banter between two friends who were dining together. Neither thought that a walk from Boston to D.C. was actually in the cards or, for that matter, even possible. As Weston recalled later, “I was not aware, at the time, that I possessed any great locomotive powers,” let alone the ability to walk nearly 500 miles.2

That changed, however, when Lincoln won the election. As Lincoln’s inauguration date got closer, Weston decided that "since he was fool enough to make the agreement, he will be man enough to fulfil it" and began to consider the logistics of completing this trek from Boston to D.C.3 On January 1, 1861, Weston tested out his legs by completing a thirty-six mile walk from Hartford to New Haven, Connecticut, which he found to be relatively easy. Noting that he “did not feel the effects of the walk at all,” he was able to make the return journey back to Hartford on foot the next morning.4

Confident that he would be able to complete a walk between Boston and Washington, D.C. without injuring himself, Weston got to work securing the supplies, and funds, necessary for the nearly 500-mile journey that awaited him. He found someone to sponsor a horse, carriage, and two men who would follow behind to carry supplies – and ensure that he traveled only by foot for all 478 miles. He publicized his itinerary in newspapers to guarantee his walk would drum up public attention.

Many were fascinated by the idea that someone would attempt to walk from Boston to D.C., in the middle of winter, though opinions varied. Davenport, Iowa’s Morning Democrat went so far as to call him “a fool on his travels”5 while another paper questioned “will he do it?”6

Other reports were more complimentary. The Hartford Courant referred to Weston’s attempt as “remarkable” due to the fact that “the feat is to be undertaken solely from a sense of honor in doing what he agreed.”7

What was undeniable is that Weston’s walk was attracting attention across the country. So much so, in fact, that he was able to drum up sponsors for this trip who provided him with funding and supplies in exchange for Weston distributing advertising pamphlets at houses he passed on his route. Among the more useful items? A rubber suit from the Rubber Clothing Company, which proved to be helpful in the wintry conditions he faced.

On February 22, 1861, the trek almost failed before it even began. A large crowd had gathered at the Boston State House in anticipation of Weston’s departure. But as he stepped out of his carriage to greet the onlookers, he was stopped by a debt collector looking to settle up on a debt Weston owed – one thing about Weston is that he was frequently in debt. When Weston made it clear that he would not be able to settle his debt until he returned from Washington, the officer informed him that he would be placed under arrest. As this was occurring, another debt collector stepped up and presented a different claim against Weston. After an hour of intense negotiation, the would-be walker was released on the condition that he pay his debts upon his return to Boston.

At a quarter to one, Weston made his way back to the State House, where he gave a brief speech at the insistence of the crowd, while explaining that he “preferred to keep his breath for the long journey.”8 Weston shared that he felt a certain calling to complete this walk: “Abraham Lincoln had been elected by the people, President of these United States, and he believed he had been elected to walk to Washington to see him inaugurated, and with God’s help he would do it.”9 Following his speech, Weston and his companions set off, with a crowd of several hundred following them down Beacon Street. He traveled the first five miles out from Boston in 47 minutes and reached his first stop in Framingham 15 minutes earlier than he had originally intended, despite his delayed departure. In Framingham, Weston and his crew were entertained at the Framingham Hotel, where he encountered a number of ladies who “desired to send a kiss to the President.” Mr. Weston gladly accepted these kisses from the ladies, but he told them he could not promise to deliver them to the president.10

As Weston continued on his journey, he encountered snow and ice in his path and at one point was chased by a dog, which led to an ankle sprain. He walked on rough and muddy roads, even while injured and in pain. In Worcester, Massachusetts, Weston encountered yet another debt collector. Despite these obstacles, Weston stated that he would “sooner die on the road than back down.”11

Weston traveled, on average, 50 miles per day during his trek. He was hosted by a number of different hotels and individuals, many of whom charged him nothing due to the press his stay would generate. At each location, he was greeted by cheering crowds who had gathered hours before in anticipation of his arrival. He often slept for only an hour at a time, typically in an odd location like on the ground next to a stove or atop a table – his longest uninterrupted sleep lasted only 6 hours and took place at a tavern in Trenton, New Jersey – and usually ate while on the move.12

Weston’s path took him through New York City, Newark, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and a number of smaller towns between. On the way from Philadelphia to Baltimore, Weston and his companions traveled 12 miles in the wrong direction. Later the same day, as he approached Port Deposit, Maryland on his way to Baltimore, Weston made a wrong turn and proceeded down the main street in his “undress uniform” which put him in a sour mood.13

Upon his arrival in Baltimore, Weston was noted to be “greatly jaded” regarding the interruptions he had faced on his trek, but “expressed great confidence in his ability to present himself in Washington.”14 On the morning of Inauguration Day, March 4, Weston and his companions left Baltimore at 6am. After walking for a bit, the group realized one of their horses was unable to proceed any farther. As the deadline for his arrival in Washington, D.C. crept closer, Weston determined that he must complete the final 30 miles of his journey alone. He picked up his pace, barely stopping to catch his breath, and finally arrived in D.C. around 5pm, with lips that were “very much parched” from the intensity of his walk.15

When Weston set foot on the Capitol grounds, he was exhausted, “sore and weak”, and declared that he “would not undertake the journey again over such roads for any sum of money.”16

When it was all said and done, he had completed his walk in 10 days, four hours, and 12 minutes, a few hours later than the bet initially stated, and the route he took ended up being approximately 510 miles long.

He arrived too late to see Lincoln sworn in, but just in time for the inaugural ball. Weston attended President Lincoln’s first levee, where he was introduced to President and Mrs. Lincoln. The Lincolns were seemingly impressed by Weston’s feat, and President Lincoln offered to pay the fare for his return trip to Boston. Apparently already forgetting about the trials of his southward journey, Weston declined this offer, explaining that since he had failed to reach Washington in 10 days like he had promised, he felt obligated to walk all the way back to Boston. As it turned out, those plans would change.

As he was preparing to head home, the Civil War broke out, so he decided to use his “pedestrian abilities in serving our government.”17 When communication was interrupted between D.C., Baltimore, and other eastern cities, Weston prepared to take a “walk in disguise” to collect letters from Boston and New York that were to be delivered to Union forces in Washington D.C. and Annapolis, Maryland.18 Ever the businessman, Weston’s memoir names the specific companies that produced his disguise: Messrs Brooks Brothers of New York provided him with clothing while Mr. G. W. White, a hatter, provided him with a hat that gave him the look of a “Susquehanna Raftsman on a bender.”19 Weston also extended his thanks yet again to the Rubber Clothing Company, who sewed an enameled cloth bag into his jacket to hold the letters.20 This journey was, unsurprisingly, not without obstacles. Weston encountered a number of individuals who were “no friend to the ‘Yankees’” and spent some nights sleeping outside in a tree or beneath the edge of a hay bale.21 Despite these difficulties, Weston’s pedestrian prowess carried him and he successfully delivered the letters.

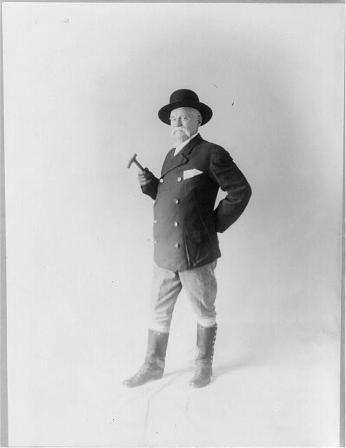

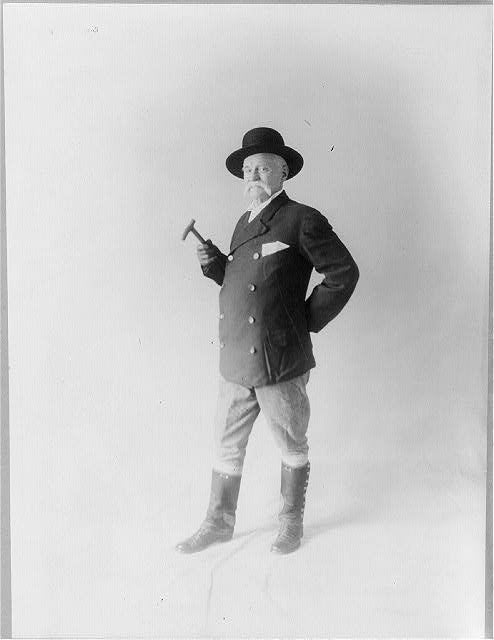

It was the start of a grand career. Following the conclusion of the Civil War, Weston became a professional pedestrian and started going by the name “Weston the Pedestrian.” His walk from Boston to D.C. had generated a lot of press and interest around not only Weston himself, but also American pedestrianism as a spectator sport.

Weston took his walking show across the country participating in walking contests, doing promotional promenades, and conducting lectures. Thousands of people would line up to buy tickets and place bets. In a country that was rebuilding following a divisive war, his walks were an apolitical – and even unifying – event. In all, Weston participated in more than 1,000 professional events in a walking career that spanned nearly seven decades.

Among his more notable accomplishments, Weston walked backwards for 200 miles around the city of St. Louis, walked from Portland, Maine to Chicago, Illinois (twice), he traveled to Europe, where he won competitions in London, outwalking his opponents with ease, and, at the age of 70, Weston walked across the country from New York City to San Francisco – a feat he intended to accomplish in 100 days; when it took 104 Weston described it as the greatest disappointment in his life. He ended up making the return journey from San Francisco to New York City in 76 days. His last great journey came in 1913, when he walked 1,546 miles from New York to Minneapolis in 51 days.

Pedestrians like Weston were some of the world’s first mass-market stars, and their fame marked the beginning of the first-age of international celebrity. At the peak of his pedestrian career, Weston was one of the most famous people in the English-speaking world. In fact, Weston was so famous that newspapers referred to him by last name only – he had achieved a level of fame that, at the time, only belonged to royalty and politicians.22

Even in the later years of his life, Weston was an advocate for walking and urged the general public to take up walking, whether it be for exercise or competition. Sadly, in 1927, he was hit by a taxi, an accident that confined him to a wheelchair until his death in 1929.

For those looking to emulate Weston the Pedestrian today, but aren’t ready to commit to a 500-mile trek between Boston and D.C., look to this 1878 New York Times article inspired by the then-growing trend of pedestrianism, which suggests that one “walk as long as [they] like and return to [their] home in the evening a happier and healthier [person]” as “nothing is more wholesome than exercise and certainly no exercise is simpler than walking.”23

Footnotes

- 1

Weston, “The Pedestrian;” Being a Correct Journal of “Incidents” on a Walk from the State House, Boston, Mass., to the U.S. Capitol, at Washington, D.C. Performed in “Ten Consecutive Days” between February 22d and March 4th, 1861, 5. "The pedestrian"; being a correct journal of "incidents" on a walk from the state house, Boston, Mass., to the U. S. capitol at Washington, D. C. ... between February 22d and March 4th, 1861 : Weston, Edward P. (Edward Payson), 1819-1879 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

- 2

Weston, 5.

- 3

“Pedestrian Feat,” Hartford Courant, January 4, 1861. Hartford Courant, 4 January 1861, p. 2. Jan 04, 1861, page 2 - Hartford Courant at Newspapers.com

- 4

Weston, 6.

- 5

“A Fool on His Travels,” The Morning Democrat, March 2, 1861. The Morning Democrat, 2 March 1861, Mar 02, 1861, page 2 - The Morning Democrat at Newspapers.com.

- 6

“Will He Do It?,” The Evening Star, January 17, 1861.

- 7

“Pedestrian Feat.” The Hartford Courant, January 4, 1861.

- 8

Weston, 11.

- 9

Weston, 11.

- 10

Weston, 12.

- 11

Weston, 15.

- 12

Tom Tapley, “The Pedestrian,” Running Past (blog), n.d. http://www.runningpast.com/pedestrian.htm.

- 13

Weston, 27.

- 14

“The Walk from Boston to Washington Accomplished.” The Baltimore Sun, 5 March 1861, p.1.

- 15

Weston, 29.

- 16

Arrival of Weston, the Boston Pedestrian.” Evening Star, 5 March 1861, p. 3 News Article, Evening Star (published as Evening Star.), March 5, 1861, p3.

- 17

Weston, 31.

- 18

Weston, 32.

- 19

Weston, 32.

- 20

Weston, 32.

- 21

Weston, 38.

- 22

Jackie Mansky, “One of America’s First Spectator Sports Was Professional Walking,” n.d., https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/one-of-americas-first-spectator-sports-was-professional-walking-180985397/.

- 23

“Views Afoot” The New York Times, 17 March 1878, *81722746.pdf.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)