Lincoln's Secret Weapon: The Telegraph

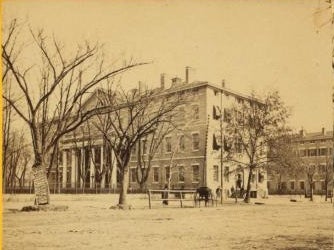

Today, we Washingtonians rely upon Twitter, smart phones, and 24-hour cable news channels to continually fill our craving for information. But a century and a half ago, during the Civil War, the only source of instantaneous news from far away was the telegraph, and in Washington, there was only one place to get it: The Department of War's headquarters building, which stood at the present site of the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, next door to the White House.

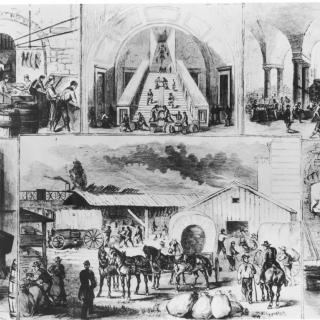

Before the war, amazingly, the government hadn't even possessed its own telegraph operation, instead relying upon the same commercial telegraph offices that civilians used. But as a recent New York Times article by historian David T. Z. Mindich details, after President Abraham Lincoln appointed Edwin G. Stanton as his Secretary of War in 1862, Stanton asked for and received sweeping powers to control information in the capital. That included the telegraph lines, which Stanton seized and had rerouted into his headquarters. The move enabled Stanton to exercise censorship over what news that journalists published about the war, and what information members of Congress were able to get. Since the White House didn't have its own telegraph connection, even the President himself had to trudge next door to receive and send messages, a scene that was depicted in the recent Steven Spielberg biopic Lincoln.

As the telegraph office manager, David Homer Bates, wrote in a memoir, "Lincoln spent more of his waking hours in the War Department telegraph office than in any other place, except the White House." Sometimes, in critical situations, Lincoln — customarily clad in a wool shawl over his suit — would spend the entire night at the office, which was located in a second-floor library that also contained shelves full of rare books, including a folio copy of Audubon's Birds of America. He spent the time in the company of Bates and various members of his team of three operators: Thomas T. Eckert, Charles A. Tinker, and Albert B. Chandler. According to Bates, the office actually provided Lincoln with a refuge from all of the responsibilities that weighed upon him. Sometimes, Bates recalled, the President would drop in and jokingly explain that he was trying "to get rid of the pestering crowd of office-seekers."

According to historian Tom Wheeler, the telegraph gave Lincoln a secret weapon no head of state had possessed in wartime up to that point. Kings and Presidents had been forced to sit in their capitals and allow generals in the field to operate and make decisions on their own, a situation that gave the generals extraordinary power. Lincoln, in contrast, used his newfangled communications tool not just to gather information, but to give orders and "put starch in the spine of his often all-too-timid generals, and to propel his leadership vision to the front," Wheeler writes. During the battle of Gettysburg, for example, Lincoln used telegraph messages to make sure that Gen. Joseph Hooker, who wanted to seize upon the Confederate advance to strike against Richmond, hewed instead to Lincoln's strategic goal of destroying the Confederate army. "I think Lee's army, and not Richmond, is your true objective point," Lincoln reminded his general, in an exchange of messages whose rapid-fire speed conveyed as much authority as if Lincoln actually had been in Hooker's tent.

But Lincoln, who visited the telegraph office several times a day, didn't just read messages from his commanders. Instead, as Bates wrote in his memoir, Lincoln would open the drawer containing copies of all the telegrams received since his previous visit, and scan through them all, regardless of whom they were addressed to. That gave Lincoln a chance to find out what information other officials in his government were getting — a useful bit of intelligence that helped him to manage the "team of rivals" in his cabinet.

Lincoln also relied upon his telegraph operators as cryptographers, employing them to decipher intercepted written messages from the Confederates. We'll get into that in another installment.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)