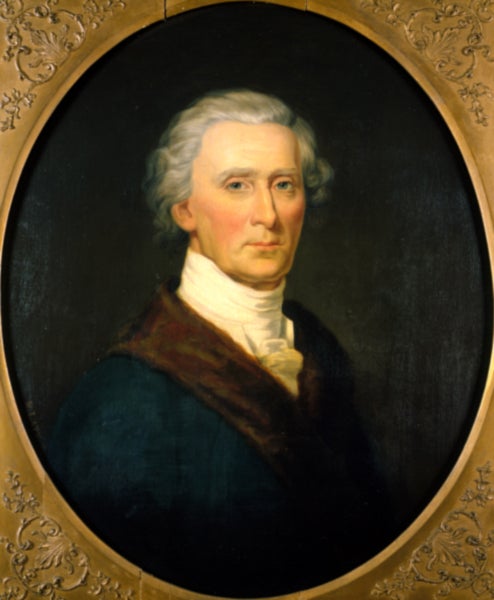

Maryland’s Charles Carroll of Carrollton Was Last Living Signer of Declaration of Independence

On November 14, 1832, the news came from a house on Lombard Street in Baltimore: the last living signer of the Declaration of Independence had died. In Maryland, flags were lowered and the courts closed.1 President Jackson proclaimed that government offices in Washington would close as a “mark of respect.”2 Planning began for a long funeral procession, attended by the governor and senators of Maryland, the Baltimore mayor and city council, U.S. Congressmen, and Revolutionary War veterans.3

But who was the man who had just died?

Though he was widely lauded in the early 1800s, modern Americans hear little about Charles Carroll today. He was starkly different from the other Founding Fathers: wealthy, educated in Europe, a devout Catholic among Protestants, and skeptical of popular rule. He never led troops or roused a crowd with speeches. Despite earning the title of Maryland’s “First Citizen,” Carroll was only active in politics for a third of his life.

Nonetheless, he risked his life and fortune to sign the Declaration of Independence, served for decades in civic and governmental roles, and was an influential voice in developing Maryland’s new state government. He was deeply opposed to corruption and struggled against religious discrimination. Carroll’s story forms part of our American history made rich by difference, and he remains recognizable to Marylanders as an original Old Line patriot.

Charles Carroll of Carrollton4 walked a fine line of contradictions from birth. He was an illegitimate child, born in 1737 to Charles Carroll of Annapolis and Elizabeth Brooke.5 The Carrolls were already second-generation Americans, but maintained close ties to Europe a relationship which would dominate Charles’ childhood. The family was also devoutly Catholic, which in Maryland deprived Charles of the right to vote, run for office, or practice law.6

The Carroll family was also one of the richest in the American Colonies. The first Carrolls had fled anti-Catholic persecution in England, arriving in Maryland in 1659 and leveraging ties to Lord Baltimore (the colony’s proprietor) to rise to wealth and social prominence. They held on to land and business interests through a Protestant-led revolution so that by Charles Carroll of Carrollton’s time, the family had acquired a £100,000 fortune ($19.1 million today).7 Even though the Carrolls and other members of Maryland’s Catholic elite were locked out of civic life, this immense wealth provided a level of security and influence.

As a child, Charles (Charly to his family) received his education at a secret Catholic school in Cecil County with the children of other Catholic elites. At age 11, his father sent him to St. Omer Jesuit school in France. There, he learned Jesuit philosophy upon which he based his later political beliefs, as well as history, poetry, and law.

At his father’s direction, Charles continued his legal studies in London for a further ten years. As a Catholic, he was not permitted to officially study law and learned instead through private tutoring and observation.8 Connecting himself to London’s aristocracy, he “fully indulged” in gentlemanly pursuits: “dancing, fencing, drawing, and learning Italian.”9 By the time he returned to Maryland in 1765, he possessed something no other Founding Father did: an understanding of the legal and political implications of the American question from a British perspective. His time in London had shaken his faith in Britain’s ability to govern the colonies.

These experiences and Carroll’s mixed background of aristocratic wealth and political exclusion would put him on the path to his first political engagement. This clash would elevate Charles from private aristocrat to Maryland’s “First Citizen.”

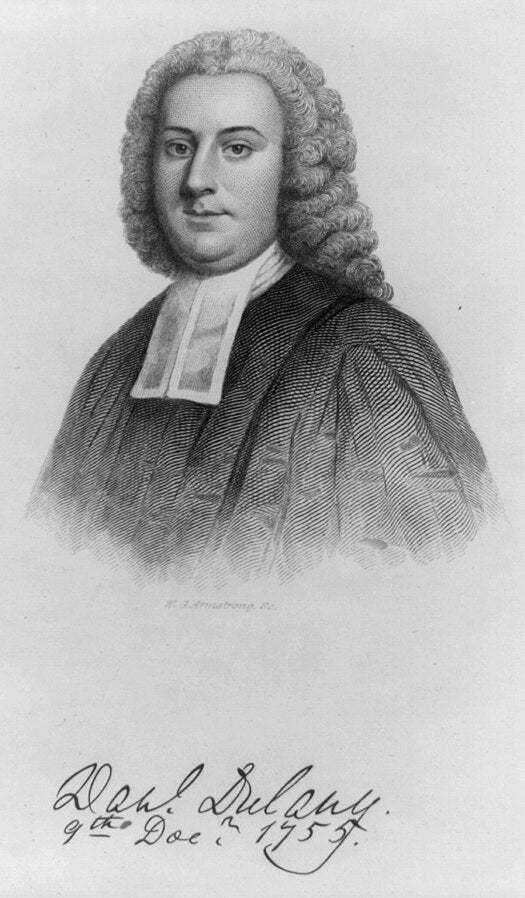

In 1770, the lower house of Maryland’s legislature refused to raise fees paid to public officials. When the governor implemented them without legislative consent, controversy sparked among colonists resentful of British authority. To defend the decision, constitutional tax expert Daniel Dulany wrote a series of dialogues between two citizens in the Maryland Gazette. In each, Dulany as the “second citizen” easily and eloquently dismantled the arguments of a straw-man “first citizen” who opposed the new fees.

It was then that Charles Carroll chose to act. He began writing letters to the Gazette as the “First Citizen,” criticizing the taxes and governmental overreach. He argued against the oligarchy of Protestant families that controlled Maryland politics and in favor of expanding religious freedom.

The authors “laced their essays with Latin,” showing off their educations in history and law.10 The identities of the two “citizens” became common knowledge and the exchange put both men in the spotlight. When it became clear that Dulany was losing, he resorted to highly personal attacks on Carroll. He called his opponent a Jacobin and Jesuit, and questioned whether Carroll, as a Catholic, even had a right to free speech.11

Carroll’s restraint and well-argued responses won him praise and admiration from Marylanders, and he was recognized as the winner of the Gazette spat. The incident gave him the moniker of “First Citizen” and a reputation as a prominent critic of British rule. He was appointed to the Annapolis Committee of Correspondence and Council of Safety, and later served on the Maryland Committee of the same.

Soon, he was elected to the 2nd Maryland Convention in 1775, becoming the first Catholic to hold Maryland political office in nearly a century.12 A slew of elections and appointments followed. He served as an Alderman and Councilman for Annapolis. He helped pen the 1776 Maryland Constitution, which again officially enshrined religious freedom. Alongside Benjamin Franklin, he journeyed as a diplomat to Quebec, though his Catholic background and fluent French were insufficient to make allies of the Canadians.

But what had spurred Charles Carroll, who had never participated in politics before, to plunge into the “First Citizen” debates that began his civic service?

Carroll’s education—European and Catholic—deeply influenced his political beliefs. At St. Omer, he learned Christian philosophies of limited civil government and classical conceptions of natural law. He read St. Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologica, in which the philosopher wrote: “The validity of law depends on its justice… Man in bound to obey secular rulers to the extend that the order of justice requires.”13

During his time in England, he witnessed “the excesses of the English system and the corruptions present in the Parliament” which helped convince Carroll that America needed to extricate itself from British political rot.14 He wrote to his father throughout the 1760s of possible American independence.

Freedom of religion also played an important role in Carroll’s political judgements. As a repressed minority, he judged that the only way to recover religious and civil rights for Catholics was to restore the original Maryland Constitution, which could not happen under British control.15 Indeed, he wrote to a friend in 1829 that when he signed the Declaration of Independence he was thinking “not only [of] our independence of England, but the toleration of all sects professing the Christian religion, and communicating to them all equal rights.”16

All of these new positions of political leadership culminated in Carroll’s nomination as a delegate to the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776. In a popular retelling of the document’s signing, Carroll had finished writing his name Charles Carroll when another delegate, possibly John Hancock, mocked him for protecting his wealth by hiding behind his common name. Without another word, Carrollton stepped back up to the desk and added of Carrollton, making his identity unmistakable.

Another delegate reportedly whispered, “There goes another million.”17

In reality, Carroll began including of Carrollton in his signature years prior to distinguish himself from his father, so the story is likely myth. But it is true that Carroll took a great risk to himself, his family, and his property by identifying himself so conspicuously in favor of establishing a new republic.

Of course, Carroll’s dedication to democracy had its limits. He was one of the most conservative Founders, preferring a government “rooted in the classical, medieval, and English traditions.”18 He was reputedly the largest slaveowner in America and as a Senator opposed measures that threatened the wealth of pre-Revolutionary elites.19

Unlike Founding Fathers like Thomas Paine, Carroll mistrusted the general populace’s ability to govern itself fairly. In 1776, Carroll witnessed chaos erupt in Maryland. Baltimore revolutionaries exacted violent revenge on Loyalists while Tories and free Blacks on the Eastern Shore were in open revolt. Carroll worried about an “ungovernable and resentful Democracy” developing after the war and suggested limited suffrage to landowners and a legislative upper chamber to check a more democratic lower house.20

These philosophies and his personal experiences helped guide his long career in politics as the first US Senator from Maryland and serving twenty-nine years as a state senator. Constantly busy, Carroll was known for his level head, educated opinions, and mind for business and diplomacy. He served on the committee that approved and finalized the wording of the Constitution and Bill of Rights and opposed laws depriving defeated Loyalists of their rights. In 1801, he retired from political office and public life.

But Carroll had plenty else to occupy him. His family was at the top of Maryland society and fabulously wealthy. The Carroll estates comprised more than 100,000 acres of orchards, fields, livestock, mills, and small factories.21 He managed manors in Annapolis, Baltimore, Ellicott City, and Frederick and hosted major social events.

While professing philosophically to oppose slavery, Carroll remained a major slave owner for the rest of his life. Though far from an abolitionist, he was involved in some measures to change the American system of slavery. He introduced a bill to gradually abolish slavery in Maryland (which ultimately failed) and served as president of the Maryland branch of the American Colonization Society, which sought to resettle Black Americans in Africa.22

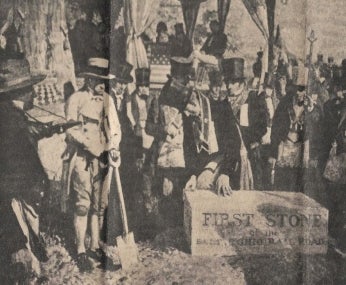

Carroll also pursued business interests into his nineties. A prolific entrepreneur, he invested his fortune in turnpike, bridge, and water enterprises, as well as the Patowmack Company, which dug canals in the Potomac and Shenandoah valleys, and its successor, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Company.23 He invested in the Banks of Maryland and Baltimore, and the First and Second Banks of the United States. In 1828 he laid the cornerstone of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad at the age of 91.

In part, Carroll became so famous because he lived for so long. As the last surviving Signer, he became “a monument to the first defining act of the American nation.”24 In his later years, Carroll himself professed that the acclaim he received was a little exaggerated, but hoped he would be remembered for his “integrity, a sincere love of my country, a detestation of Tyranny.”25

When he died, Americans lost their last living connection to the nation’s birth. But Carroll is remembered today, if not so much in textbooks than certainly in quieter influences. His manors are now museums and Historic Landmarks open to the public, Carroll is the namesake of counties in a dozen states, and Charles is one of two Maryland statues in the Capitol. He also left behind a complicated legacy that poses questions about class, exclusion, civic duty, and who gets to have a voice in our republic.

Footnotes

- 1

New-Hampshire statesman and state journal. (Concord, NH), Nov. 24 1832. https://www.loc.gov/item/sn84022931/1832-11-24/ed-1/.

- 2

Providence patriot, Columbian phenix. (Providence, RI), Nov. 24 1832. https://www.loc.gov/item/sn83025643/1832-11-24/ed-1/.

- 3

Daily National Intelligencer. (Washington, DC), Nov. 19 1832. https://www.loc.gov/item/sn83026172/1832-11-19/ed-1/.

- 4

Three generations of Carrolls were all named Charles. The name was also common outside of the family, so each distinguished himself by adding a locational epithet to their first names.

- 5

The couple remained unwed because of legal technicalities within Maryland inheritance law. In order to maintain control of his estate, Charles of Annapolis would only marry Elizabeth when his son was almost of legal age.

- 6

Maryland’s Act of Toleration (1649) originally established freedom of religion in the colony. However, by the time Charles was born, the Act had been repealed during Maryland’s Protestant Revolution and the Church of England established as the official religion of the colony. Catholics were banned from celebrating Mass, voting, or raising children in the Catholic faith. Freedom of religion would not be restored until 1776.

- 7

CULLEN, FINTAN. “Charles Carroll of Carrollton: Painting the Portrait of an Irish-American Aristocrat.” Eighteenth-Century Ireland / Iris an Dá Chultúr 25 (2010): 149–60. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41430814.

- 8

Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence. “Charles Carroll of Carrollton,” May 25, 2022. https://www.dsdi1776.com/signer/charles-carroll-of-carrollton/.

- 9

CULLEN, FINTAN. “Charles Carroll of Carrollton: Painting the Portrait of an Irish-American Aristocrat.” Eighteenth-Century Ireland / Iris an Dá Chultúr 25 (2010): 149–60. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41430814.

- 10

Maier, Pauline. The Old Revolutionaries. Knopf, 2013. https://archive.org/details/oldrevolutionari00paul/page/205/mode/1up?q=carroll

- 11

Ibid. Dulany himself was a converted Catholic, having renounced Catholicism for Anglicanism in return for the right to practice law and participate in politics.

- 12

Maryland State Archives. “Charles Carroll of Carrollton, MSA SC 3520-209,” 2015. https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/000200/000209/html/209extbio.html.

- 13

D’Elia, Donald. “Charles Carroll of Carrollton: Catholic Revolutionary.” The Journal of Christendom College 4, no. 2 (1978).

- 14

Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence. “Charles Carroll of Carrollton,” May 25, 2022. https://www.dsdi1776.com/signer/charles-carroll-of-carrollton/.

- 15

D’Elia, Donald. “Charles Carroll of Carrollton: Catholic Revolutionary.” The Journal of Christendom College 4, no. 2 (1978). https://media.christendom.edu/1978/07/charles-carroll-of-carrollton-catholic-revolutionary/

- 16

Griffin, Martin Ignatius Joseph. Catholics and the American Revolution. Ridley Park, PA, 1907. https://archive.org/details/CatholicsAndTheAmericanRevolutionV1/page/n380/mode/1up?q=carroll.

- 17

Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence. “Charles Carroll of Carrollton,” May 25, 2022. https://www.dsdi1776.com/signer/charles-carroll-of-carrollton/.

- 18

Birzer, Bradley J. American Cicero: The Life of Charles Carroll. Open Road Media, 2014. https://archive.org/details/americanciceroli0000brad/page/n13/mode/1up

- 19

For example, Carroll opposed the Tender Act, which forced creditors to accept paper money at a loss. Eventually, Carroll decided (much to his father’s outrage) to support the Act, as he decided that it was in the best interests of the country.

- 20

Maier, Pauline. The Old Revolutionaries. Knopf, 2013. https://archive.org/details/oldrevolutionari00paul/page/205/mode/1up?q=carroll

- 21

Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence. “Charles Carroll of Carrollton,” May 25, 2022. https://www.dsdi1776.com/signer/charles-carroll-of-carrollton/.

- 22

Leonard, Lewis Alexander. Life of Charles Carroll of Carrollton, 1918. p.218

- 23

Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence. “Charles Carroll of Carrollton,” May 25, 2022. https://www.dsdi1776.com/signer/charles-carroll-of-carrollton/.

- 24

Maier, Pauline. The Old Revolutionaries. Knopf, 2013. https://archive.org/details/oldrevolutionari00paul/page/205/mode/1up?q=carroll

- 25

Maier, Pauline. The Old Revolutionaries. Knopf, 2013. https://archive.org/details/oldrevolutionari00paul/page/205/mode/1up?q=carroll

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)