The Legacy of the Annapolis Liberty Tree

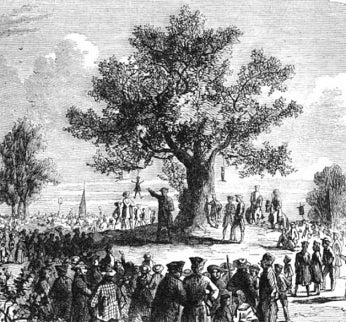

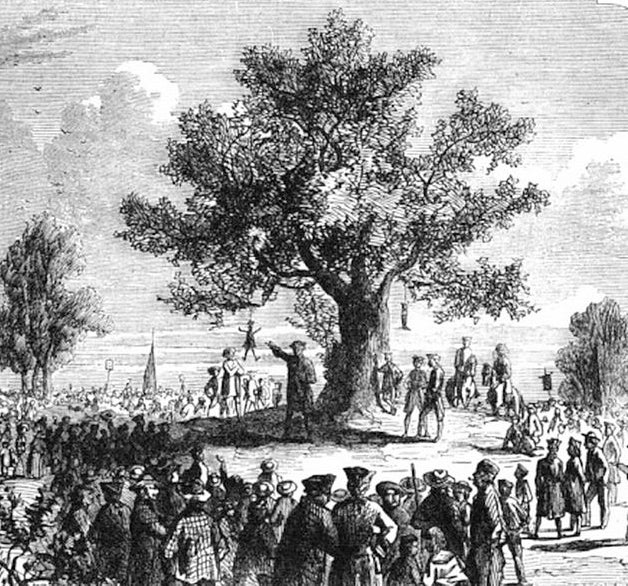

On April 14, 1765, a crowd of angry Bostonians formed below a large tree at the corners of Essex and Orange Streets. Britain had just passed the Stamp Act, which imposed a tax on popular paper products, and the Massachusetts colonists were not happy about it. Protestors used the tree’s branches to string up effigies of government administrators who enforced the new taxes, accompanied by a sign which read, “What Greater Joy did ever New England see than a Stampman hanging on a Tree!”1 This act of defiance went down in history as one of the first acts of American resistance to British rule—and suddenly, this perfectly ordinary Boston elm tree became the most famous in the thirteen colonies. As Revolutionary fervor heated up in Boston, the tree became a regular meeting place for protestors, including the famous Sons of Liberty. But in April 1775, as war began to break out between the colonists and the government, British soldiers and Loyalists cut down the tree, hoping to bring a symbolic end to the protests.2

It didn’t work. Perhaps unbeknownst to those soldiers in Boston, “Liberty Trees” had sprung up all over the American colonies since 1765, new symbols of opposition to British rule. There may have been hundreds of these trees designated up and down the Eastern seaboard, from small towns in New England to bustling cities like New York and Philadelphia.3 In our area, the most well-known Liberty Tree stood in Annapolis.

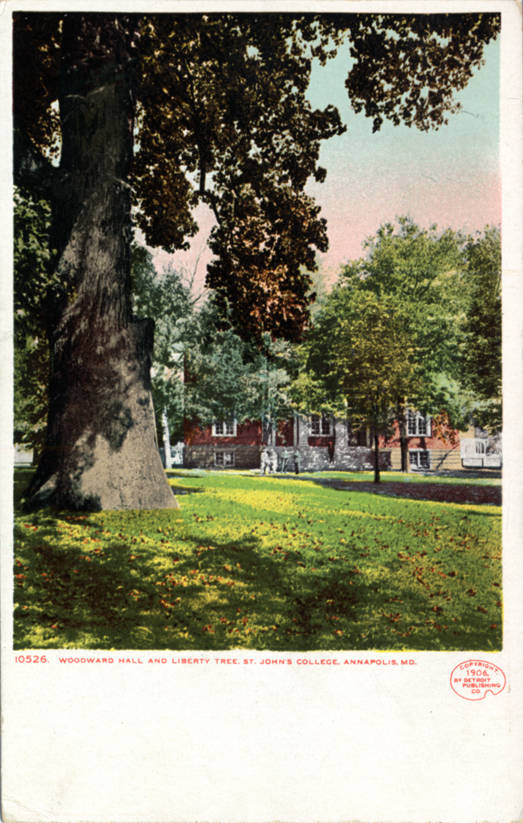

The Annapolis Liberty Tree was a tulip poplar that grew a few blocks away from the Maryland State House, on grounds that would soon become the campus of St. John’s College. It was already massive in the 1770s—estimated to be at least 100 years old by then, it may have even predated the founding of the Maryland colony in 1634.4 Just as in Boston, this tree served as a landmark and gathering place for the city’s Patriot groups. The Annapolis chapter of the Sons of Liberty—founded by Samuel Chase and William Paca, future signers of the Declaration of Independence—met at the tree to devise protests that echoed similar demonstrations throughout the colonies, including Annapolis’s very own “tea party.” When Annapolitans floated the idea of banning British Loyalists from their city, they debated the issue under the tree’s branches. It became an unlikely witness to Marylanders’ struggle for Independence in the 1770s.

After the Revolutionary War began, Liberty Trees became a target for destruction by British soldiers, desperate to rid American cities of any treasonous monuments. But unlike many other cities, Annapolis never fell under British control during the war—meaning the Liberty Tree survived the war unharmed.5 It still stood when, in 1783, George Washington rode to the State House to resign his commission as General of the Continental Army, the symbolic ending of the Revolution.

The tree’s fame really began after the war, when Americans were already mythologizing the events that led to their new nation’s founding. While Bostonians created memorials around the stump of their original tree, Annapolitans prided themselves on having theirs intact—one of a handful that survived throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. When St. John’s College was officially established in 1784, they became the new caretakers of the tree, immediately recognizing its significance and making efforts to preserve it. Famous visitors included George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette, heroes of the war—Lafayette noted that, inspired by this American symbol of political freedom, thousands of Liberty Trees were planted during the French Revolution in his home country.6 Groundskeepers at the college also planted new Liberty Trees, scions of the original, as early as the 1880s.7

But by the turn of the twentieth century, the tree was showing noticeable signs of aging. The massive trunk was nearly hollowed out by decay and could no longer support the heavy, towering branches. In 1907, preservationists filled the trunk with fifty tons of concrete to restore its integrity, also installing iron rod supports under the heaviest branches.8 As decades passed and other Liberty Trees succumbed to time, the Annapolis tree lived on—perhaps becoming the oldest of the surviving trees in the United States.

Unfortunately, these and similar efforts to keep the Liberty Tree alive were no match for Mother Nature. In 1999, the winds of Hurricane Floyd dealt a devastating blow to the tree, at that point estimated to be about 400 years old. “The oldest living survivor of America’s Revolutionary War era is in critical condition,” the Washington Post reported, as Marylanders grew concerned for one of their most important living monuments.9 After assessing a growing crack in the trunk, arborists determined that the tree was beyond saving. St. John’s College made the difficult decision to fell the tree.

But the story of the Annapolis Liberty Tree doesn’t end there. Thanks to modern science, arborists and college researchers discovered something extraordinary: that one of the scions planted in the 1880s was an exact replica of the original Liberty Tree, down to the DNA.10 This tree still stands on the grounds, and its seeds allow arborists to create more descendants of the Liberty Tree than ever before. There are hundreds throughout the state of Maryland alone—there’s even one on the grounds of the U.S. Capitol, representative of the many that once stood throughout the original thirteen colonies.11 So while the original witness tree may be gone, it still endures as a symbol of American Patriotism—and the role Marylanders played in the Revolution.

Footnotes

- 1

Mark Maloy, “The Boston Liberty Tree,” American Battlefield Trust (22 April 2024), https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/boston-liberty-tree

- 2

Ibid.

- 3

Erin Blakemore, “Why ‘Liberty Trees’ Became an Obsession After the Revolutionary War,” History Channel, https://www.history.com/articles/liberty-trees-symbol-revolutionary-war

- 4

Katharine Stanley Nicholson, Historic American Trees (Frye Publishing Company: 1922), 28.

- 5

Edward C. Papenfuse, “What’s in a Name? Why Should We Remember? The Liberty Tree on St. John’s College Campus, Annapolis, Maryland,” transcript of remarks given 2000, https://msa.maryland.gov/msa/educ/html/liberty.html

- 6

Ibid.

- 7

Tim Pratt, “Liberty Tree Project Grows,” St. John’s College (28 February 2018), https://www.sjc.edu/news/liberty-tree-project-grows

- 8

Nicholson, 28-29.

- 9

Jefferson Morley, “State’s Liberty Tree Damaged by Storm,” The Washington Post (30 September 1999), https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1999/09/30/states-liberty-tree-damaged-by-storm/88959ea0-1559-49e7-b8ab-06c9b28264ab/

- 10

Pratt, “Liberty Tree Project Grows.”

- 11

“Trees,” U.S. Capitol Visitors Center, https://www.visitthecapitol.gov/apps/grounds/trees/

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)