How Washington Saved Folk Music

Sure, it seems a bit counterintuitive. How could the favorite subject of protest music also be its greatest protector? Well, believe it. If it wasn't for Alan Lomax and the Archive of American Folk Song at the Library of Congress there might not be a Woody Guthrie — and thus by extension — a Bob Dylan or a Bruce Springsteen, and well … you get the rest.

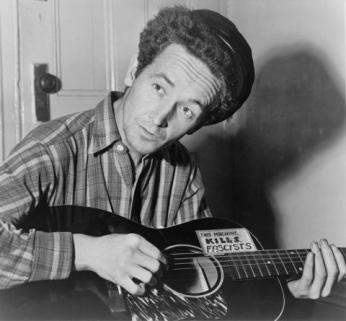

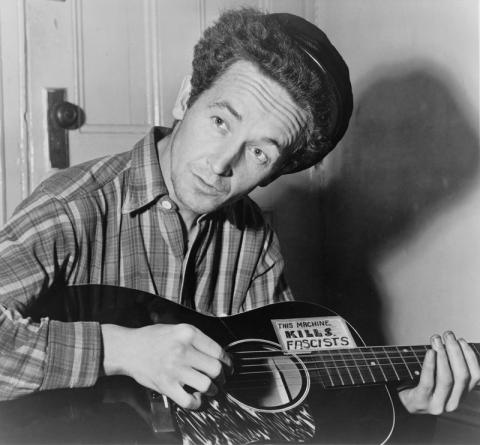

Woody Guthrie is now considered one of America's greatest folk musicians, if for no other reason than for penning This Land is Your Land (don’t miss the "censored" lyrics at the end). 2012 also happens to be his 100th birthday, so there have been a lot of hootenannies, lectures and films going on. He's kind of a big deal for a lot of reasons. But Guthrie's path to cultural relevance, and our collective memory about his life and songs, would have been greatly compromised if not for the preservation work of Alan Lomax and his colleagues at the Library of Congress.

Woody Guthrie, born in Okemah, Oklahoma in 1912, moved from Pampa, Texas to California after the great Dust Storms ravaged huge swaths of the Midwestern farmland. There, he toured migrant labor camps documenting poor conditions and injustices. He also performed on a Los Angeles radio station, singing old-time folk songs, often updated with his own lyrics about contemporary issues. But Guthrie was hardly a well-known performer when Alan Lomax, assistant in charge of the Archive of American Folk Song at the Library of Congress, first heard him at a concert in New York City in 1940.

In March 1940, Lomax arranged for Guthrie to travel to Washington, D.C. to record traditional ballads and his original songs at the Department of the Interior recording lab.

What emerged from three days of sessions is one of the purest documents of Americana ever released. This collection of "songs and conversation" features Guthrie classics such as "Do Re Mi," "Pretty Boy Floyd," "They Laid Jesus Christ in His Grave," and "I Ain't Got No Home." Interspersed are autobiographical reminiscences of his boyhood in Oklahoma and his freight-train-riding hobo days as well as his biting, wry observations of the effects on the common man of everything from the Depression to crooked politicians. That the U.S. government paid for this is as ironic as it is miraculous.

Afterward, Lomax was instrumental in helping Guthrie secure a recording contract with Victor, which resulted in the album Dust Bowl Ballads, and launched his career as a national radio personality.

In addition to Lomax's recording and promotional efforts, his correspondence with Guthrie from 1940-1950, now preserved at the Library of Congress, provides valuable historical insights into Guthrie's life and art. These letters explored political issues, current events, career and recording issues, and sometimes included illustrations.

One notable exchange occurred in a letter of September 19, 1940, when Guthrie provided commentary on the politics of the day and his own personal definition of "folk music":

The Library of Congress is good. It has helped me a lot by recording what I had to say and to copy all of my songs and file them away so the senators caint find them. Course they're always there in case they ever get a few snorts under their vest and want to sing. I think real folk stuff scares most of the boys around Washington. A folk song is whats wrong and how to fix it, or it could be whose hungry and where their mouth is or whose out of work and where the job is or whose broke and where the money is or whose carrying a gun and where the peace is — thats folk lore and folks made it up because they seen that the politicians couldnt find nothing to fix or nobody to feed or give a job of work.

After the war ended, the Library of Congress contacted Guthrie to see if he would be interested in returning to Washington to record some new songs. This letter from March 29, 1946 reveals Guthrie’s interesting perspective on the capital city:

You ask me if there is any likelihood if I will be in Washingtown during the spring? Well, I could be. ... I never have learned what it is about that place around there that I like but I know that I do. I like it like I like radio station WNYC, or the post office, or something.

I will be happy and awful glad to work with you to make my collection there more complete and up to date and whatever you can think of while we are there. Washington if it wasn't for some of the rattiest slums I've seen is the prettiest place I ever did see in the spring.

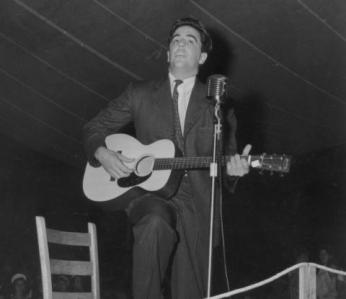

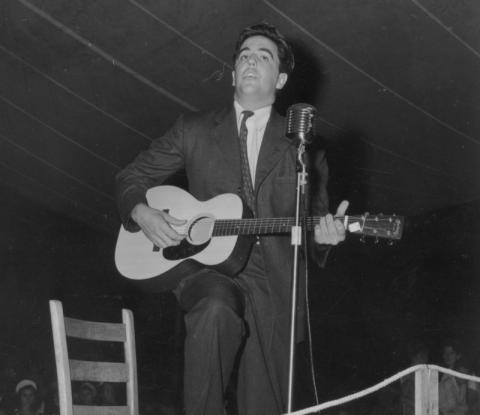

Unfortunately though, this second recording session never took place due to budget cuts at the Library of Congress and there is no record of Guthrie ever returning to the city. The amazing work done by Lomax and the Library of Congress remains one of the most important documentation projects in the history of folk music. These materials were also instrumental in helping inspire and inform a new generation of folk musicians who emerged in the folk revival of the late 1950s and 1960s, including Phil Ochs, Joan Baez, and most famously, Bob Dylan.

Sources:

Library of Congress: Woody Guthrie manuscript collection, 1935-1950

Woody Guthrie and the Archive of American Folk Song: Correspondence, 1940-1950

Which Side Are You On?: An Inside History of the Folk Music Revival in America

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)