When Autumn in D.C. Felt Like an Appalachian Spring

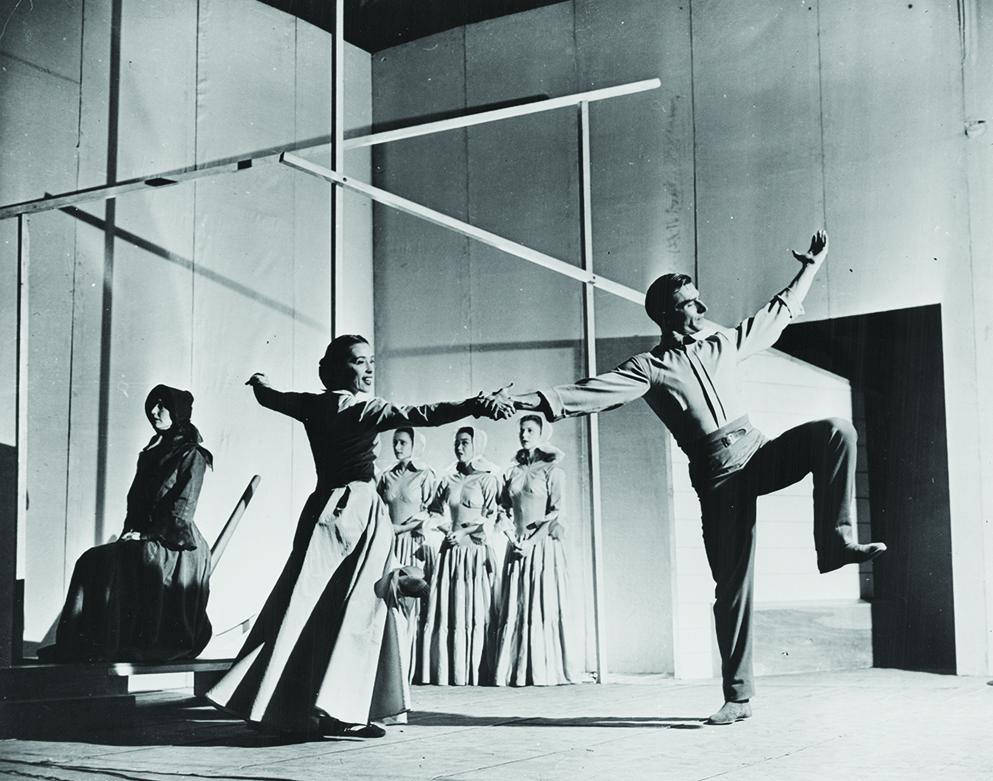

On the evening of October 30, 1944, hundreds of people filled the seats of the Coolidge Auditorium in the Library of Congress for the 10th annual festival of chamber music. In the last performance of the night, the audience was transported to rural, 1800’s Pennsylvania through Aaron Copland’s musical masterpiece, Appalachian Spring. The ballet, featuring choreography by renowned American dancer, Martha Graham, enjoyed an overwhelmingly positive premiere that night, and became the most well-known piece of music commissioned by the Coolidge Foundation and Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge—the “patron saint of American music.”

The original idea for the commission came in 1942, when Eric Hawkins, Martha Graham’s dance partner and future husband, wrote to Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge suggesting that she commission a work from Graham.[1] Graham, known as the “mother of modern dance,” rose to prominence in the 1930’s, and choreographed dances almost exclusively to original scores—of which she was often limited due to lack of funds.[2] When Coolidge and the Foundation agreed to a commission, Graham was overjoyed, and told Coolidge that it made her “feel that American dance ha[d] turned a corner, [and] it ha[d] come of age.”[3]

With a choreographer in place, Coolidge turned her focus to securing a composer. She expressed concern to the Library of Congress Music Division chief, Harold Spivacke, that some of her preferred composers might not be willing to accept her $500 commissioning fee, but Spivacke still encouraged her to reach out to those composers with the hope that they would be attracted by Martha Graham’s reputation.

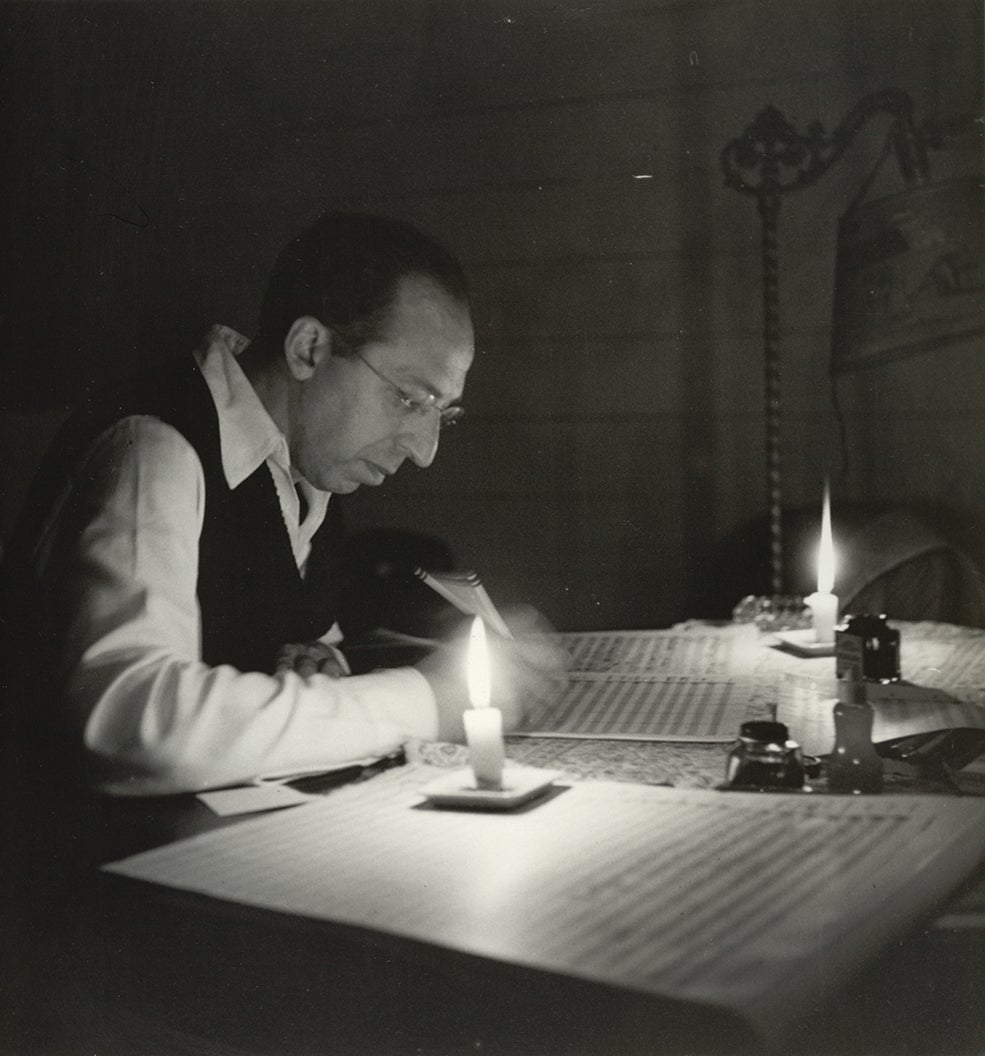

This was exactly what occurred when Coolidge wrote to prominent American composer, Aaron Copland. Copland responded: “I have been an admirer of Martha Graham’s work for many years and I have more than once hoped that we might collaborate.” This was exactly what occurred when Coolidge wrote to prominent American composer, Aaron Copland. Copland responded: “I have been an admirer of Martha Graham’s work for many years and I have more than once hoped that we might collaborate.”[4] In fact, while Appalachian Spring was a work in progress, Copland referred to it as “Ballet for Martha.” He also took on the commission, however, because he was intrigued by the theme of simple frontier life, which, according to Elizabeth Coolidge biographer Cyrilla Barr, “drew from him some of his best expressions of Americana in the form of hymn-like melodies and fiddle tunes.”

The next question was what sort of orchestra would bring Copland’s “hymn-like melodies and fiddle tunes” to life. Elizabeth Coolidge, passionate patron of chamber music, felt strongly that Appalachian Spring should be “true chamber music which is to say for an ensemble of not more than 10 or 12 instruments” in order to best suit the acoustics of the Coolidge Auditorium.[5] The auditorium was near and dear to Coolidge, as it not only bore her name, but she was the driving force in its creation.

Coolidge became friendly with Carl Engel, Chief of the Music Division at the Library of Congress in 1919. In 1922, Engel wrote to Coolidge inviting her to donate her “fine collection” of autograph musical manuscripts (handwritten musical scores) to the Library, which she gifted with the “explicit desire to have her scores performed at the Library of Congress by the winning quartet of the Berkshire Festival.”[6] Engel arranged for this concert to be held at the Freer Gallery of Art in February of 1924, since the Library did not have a dedicated performance space of its own.[7] This concert was a grand success, and was even followed by a reception at the White House, hosted by President Coolidge and the First Lady. Interestingly, Elizabeth Coolidge, who was a distant cousin of the President, was often mistakenly thought to be the first lady and jokingly referred to herself as “the other Mrs. Coolidge.”[8]

The success of the first concert inspired Coolidge to turn her attention to establishing a more permanent home for chamber concerts in the District. Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam invited her to join the Library’s division chiefs for their “roundtable” lunch, where they discussed a plan to bring chamber music festivals to the Library.[9] Coolidge suggested establishing a trust fund for performances and commissions, and proposed the construction of a brand new auditorium for the Library—which she would generously finance. In a November 1924 letter Coolidge wrote:

“In pursuance of my desire to increase the resources of the Music Division of the Library of Congress, especially in the promotion of chamber music...I offer to the Congress of the United States, the sum of $60,000 for the construction and equipment of an auditorium which shall be planned for and dedicated to the performance of chamber music, but shall also be available...for any other suitable purpose, secondary to the needs of the Music Division.” [10]

According to the Library of Congress:

“Engel and Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam (1861–1955) enthusiastically endorsed the idea. It took an act of Congress to accept [Coolidge’s] unprecedented gift. Engel proposed that the auditorium be built in a courtyard that adjoined the Music Division. His practical, yet brilliant, idea avoided purchasing additional land, utilized existing walls, and reduced the cost of heating, ventilation, and lighting systems. Engel dedicated the savings to the creation of ‘the most perfect and beautiful room for music’ that ‘the most competent minds can evolve.’” [11]

The auditorium was completed in the fall of 1925, and has been filled with chamber music masterpieces, like Appalachian Spring ever since.

On the night that Appalachian Spring premiered in 1944, the program also included two other Coolidge Foundation commissions—Darius Milhaud’s Imagined Wing and Paul Hindemith’s Mirror Before Me, both featuring dances accompanied by chamber ensembles.[12] Despite the excellence of the rest of the program, the detail and care put into the creation and execution of Appalachian Spring made the piece stand out among the rest. John Martin of the New York Times wrote of the night:

“Perhaps the real triumph of the program is “Appalachian Spring,” for which Aaron Copland has written a score of fresh and singing beauty. It is, on its surface, a piece of early Americana, but in reality it is a celebration of the human spirit. The action centers around a husbandman and his bride who have built a house and dedicate it with their friends and fellows. Nothing Miss Graham has done before has had such deep joyousness about it. There is throughout the work a very moving sense of the future, of the fine and simple idealism which animates the highest human motives. The work reaches its peak in a solo by Miss Graham as the bride, which is an extraordinarily affecting presentation of joyous young vision. Erick Hawkins, Mence Cunningham, Miss O’Donnell and the others give her notable support in a truly beautiful work.” [13]

Perhaps the entire evening emanated Appalachian Spring itself in being “a celebration of the human spirit,” as Martin wrote. At intermission, the Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish presented Mrs. Coolidge with a “declaration of gratitude,” signed by President Roosevelt in recognition of her 80th birthday and generous gifts to the Library of Congress in the furtherance of chamber music.[14] MacLeish remarked that “[Mrs. Coolidge did] what none before her had found the means to do—given the music on the shelves of the Library a living voice and let the people hear it.”[15]

This was certainly the case with Appalachian Spring, for which Copland received the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 1945. [16] Copland also completed a fully symphonic version of the complete score in 1954, which, along with the ballet still performed by the Martha Graham Dance Company, continues to showcase classic Americana for countless audiences in and out of the District.

Watch and listen to the opening of Appalachian Spring featuring Martha Graham below:

Footnotes

- ^ Allen, Erin. 2014. “Documenting Dance: The Making of ‘Appalachian Spring’ | Library of Congress Blog.” Webpage. October 9, 2014. https://doi.org///blogs.loc.gov/loc/2014/10/documenting-dance-the-makin….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Wilson, Lain. 2017. “Coolidge Auditorium — Dumbarton Oaks.” Page. https://www.doaks.org/resources/cultural-philanthropy/coolidge-auditori….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “From the Berkshire Hills to Capitol Hill - Chamber Music: The Life and Legacy of Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge | Exhibitions (Library of Congress).” Web page. August 13, 2015. https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/elizabeth-sprague-coolidge-chamber-music/f….

- ^ “Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge.” Online text. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200152688/.

- ^ Wilson, Lain. 2017. “Coolidge Auditorium — Dumbarton Oaks.” Page. https://www.doaks.org/resources/cultural-philanthropy/coolidge-auditori….

- ^ “From the Berkshire Hills to Capitol Hill.” Library of Congress.

- ^ New York Times. 1944. “MRS. COOLIDGE HONORED: President Offers Gratitude for Her Gifts to Library,” October 31, 1944. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/docview/10697….

- ^ John Martin. 1944. “GRAHAM DANCERS IN FESTIVAL FINALE: Repeat Earlier Performance of Three New Works on the Library of Congress Stage.” New York Times, November 1, 1944. https://search-proquest-com.muhlenberg.idm.oclc.org/hnpnewyorktimes/doc….

- ^ New York Times. 1944. “MRS. COOLIDGE HONORED: President Offers Gratitude for Her Gifts to Library,” October 31, 1944. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/docview/10697….

- ^ “MRS. COOLIDGE HONORED.” New York Times.

- ^ Allen, Erin. 2014. “Documenting Dance: The Making of ‘Appalachian Spring’ | Library of Congress Blog.” Webpage. October 9, 2014. https://doi.org///blogs.loc.gov/loc/2014/10/documenting-dance-the-makin….

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)