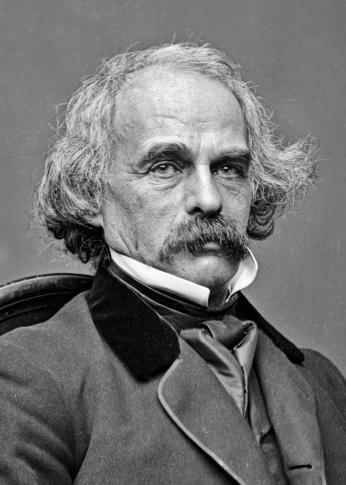

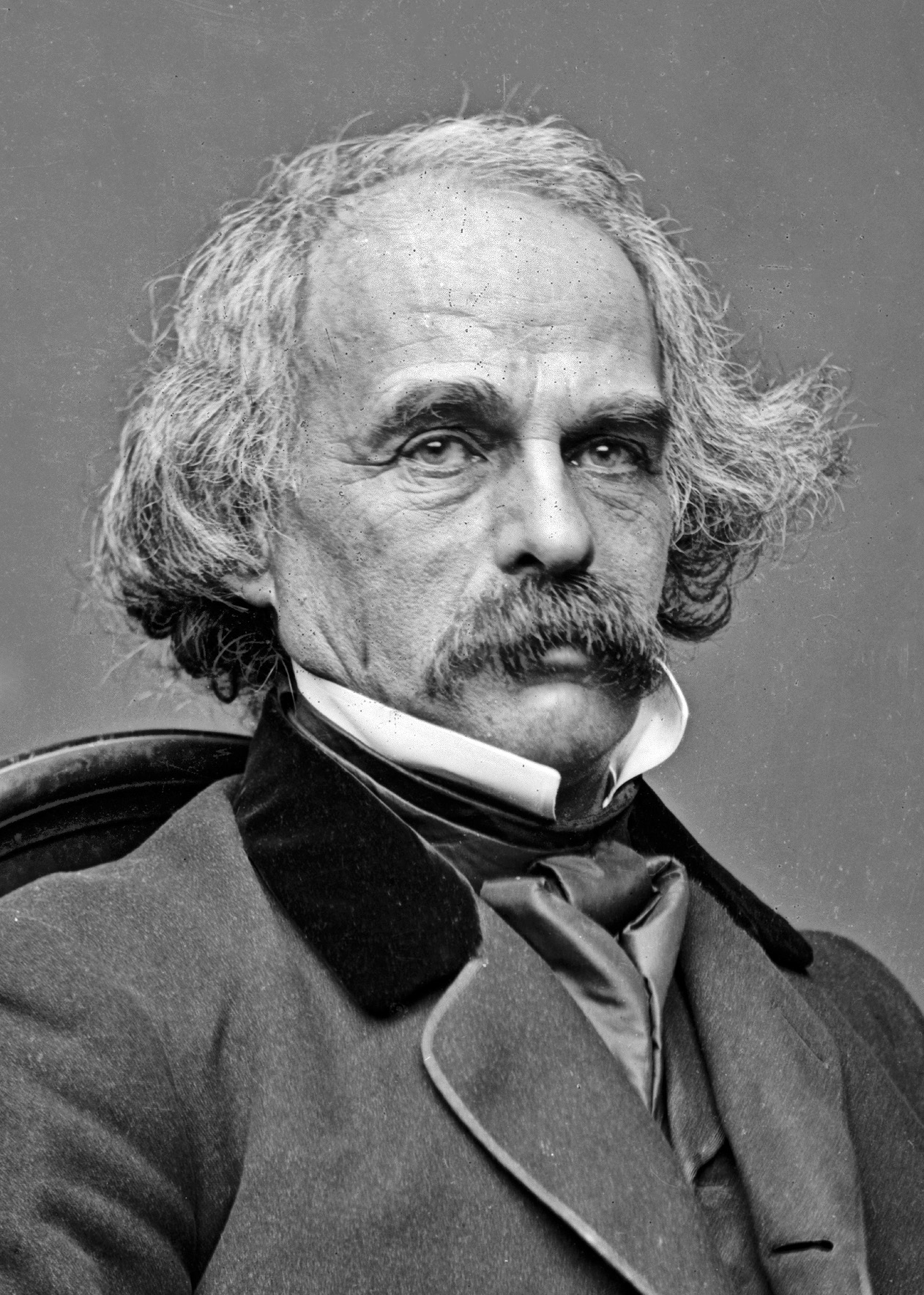

Impressions of Washington: Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1862

Nathaniel Hawthorne, author of The Scarlet Letter, visited Washington, D.C. in 1862, just as the Capital was gearing up for war against the Confederacy. If you remember Hawthorne at all from school, you won’t be surprised to find he had a lot to say.

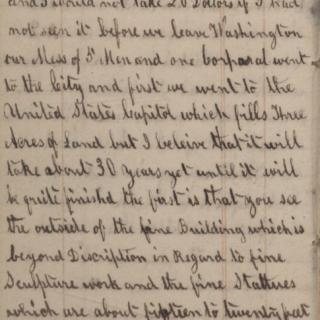

We were not in time to see Washington as a camp. On the very day of our arrival sixty thousand men had crossed the Potomac on their march towards Manassas…. The troops being gone, we had the better leisure and opportunity to look into other matters. It is natural enough to suppose that the centre and heart of Washington is the Capitol; and certainly, in its outward aspect, the world has not many statelier or more beautiful edifices, nor any, I should suppose more skillfully adapted to legislative purposes, and to all accompanying needs. But, etc., etc.

Visiting the Capitol building, Hawthorne was impressed with the beautiful Tennesee marble and characterized it as “quite a sufficient cause for objecting to the secession of that State.” During his visit there, Hawthorne met with the artist Emmanuel Leutze, who was then in the process of painting his “Westward the Course of the Empire Takes Its Way.”

Leutze allowed us to gaze at the cartoon of his great fresco, and talked about it unaffectedly, as only a man of true genius can speak of his own works.

Meanwhile the noble design spoke for itself upon the wall... [I]t would be doing this admirable painter no kind office to overlay his picture with any more of my colorless and uncertain words; so I shall merely add that it looked full of energy, hope, progress, irrepressible movement onward, all represented in a momentary pause of triumph; and it was most cheering to feel its good augury at this dismal time, when our country might seem to have arrived at such a deadly stand-still.

It was absolute comfort, indeed, to find Leutze so quietly busy at this great national work, which is destined to glow for centuries on the walls of the Capitol, if that edifice shall stand, or must share its fate, if treason shall succeed in subverting it with the Union which it represents. It was delightful to see him so calmly elaborating his design, while other men doubted and feared, or hoped treacherously, and whispered to one another that the nation would exist only a little longer, or that, if a remnant still held together, its centre and seat of government would be far northward and westward of Washington. But the artist keeps right on, firm of heart and hand, drawing his outlines with an unwavering pencil, beautifying and idealizing our rude, material life, and thus manifesting that we have an indefeasible claim to a more enduring national existence. In honest truth, what with the hope-inspiring influence of the design, and what with Leutze's undisturbed evolvement of it, I was exceedingly encouraged, and allowed these cheerful auguries to weigh against a sinister omen that was pointed out to me in another part of the Capitol. The freestone walls of the central edifice are pervaded with great cracks, and threaten to come thundering down, under the immense weight of the iron dome, — an appropriate catastrophe enough, if it should occur on the day when we drop the Southern stars out of our flag.

Not everyone in Washington was so praised by the author, however; though much was cut by Hawthorne’s editors, numerous politicians (including President Abraham Lincoln) received the sharp side of his tongue.

Everybody seems to be at Washington, and yet there is a singular dearth of imperatively noticeable people there. I question whether there are half a dozen individuals, in all kinds of eminence, at whom a stranger, wearied with the contact of a hundred moderate celebrities, would turn round to snatch a second glance. Secretary Seward, to be sure,—a pale, large-nosed, elderly man, of moderate stature, with a decided originality of gait and aspect, and a cigar in his mouth, — etc., etc.

Source:

Hawthorne, Nathaniel. Chiefly About War Matters.” The Atlantic, 1862.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)