Impressions of Washington: William Howard Russell, 1861

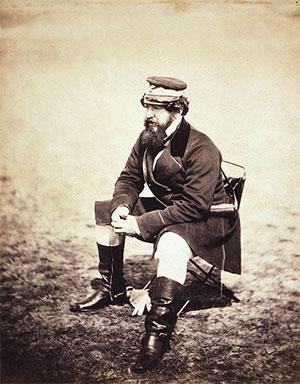

William Howard Russell (1820 – 1907) was a reporter for The Times of the UK and is considered the first war correspondent. In 1861, this intrepid reporter was sent to our very own capital to cover the Civil War. He recorded his arrival in his diary, which was later published and remains available to see exactly what this Irishman thought of Washington. Spoiler alert, he quite liked it!

March 25, 1861

I looked out and saw a vast mass of white marble towering above us on the left, stretching out in colonnaded porticoes, and long flanks of windowed masonry, and surmounted by an unfinished cupola, from which scaffold and cranes raised their black arms. This was the Capitol. To the right was a cleared space of mud, sand, and fields, studded with wooden sheds and huts, beyond which, again, could be seen rudimentary streets of small red brick houses, and some church-spires above them.

Emerging from the station, we found a vociferous crowd of blacks, who were the hackney-coachmen of the place; but Mr. Sandford had his carriage in waiting, and drove me straight to Willard’s Hotel ... Our route lay through Pennsylvania Avenue — a street of much breadth and length, lined with ailanthus trees, each in a white-washed wooden sentry-box, and by most irregularly-built houses in all kinds of material, from deal plank to marble — of all heights, and every sort of trade. Few shop-windows were open, and the principal population consisted of blacks, who were moving about on domestic affairs. At one end of the long vista there is the Capitol; and at the other, the Treasury buildings — a fine black in marble, with the usual American classical colonnades.

Close to these rises the great pile of Willard’s Hotel, now occupied by applicants for office, and by the members of the newly-assembled Congress. It is a quadrangular mass of rooms, six stories high, and some hundred yards square; and it probably contains at this moment more scheming, plotting, planning heads, more aching and joyful hearts, than any building of the same six ever held in the world... Up and down the long passages doors were opening and shutting for men with papers bulging out of their pockets, who hurried as if for their life in and out, and the building almost shook with the tread of the candidature, which did not always in its present aspect justify the correctness of the original appellation.

It was a remarkable sight, and difficult to understand unless seen. From California, Texas, from the Indian Reserves, and the Mormon Territory, from Nebraska, as from the remotest borders of Minnesota, from every portion of the vast territories of the Union, except from the Seceded States, the triumphant Republicans had winged their way to the prey.

There were crowds in the hall through which one could scarce make his way — the writing-room was crowded, and the rustle of pens rose to a little breeze — the smoking-room, the bar, the barber’s, the reception-room, the ladies’ drawing-room — all were crowded. At present not less than 2,500 people dine in the public room every day. On the kitchen floor there is a vast apartment, a hall without carpets or any furniture but plain chairs and tables, which are ranged in close rows, at which flocks of people are feeding, or discoursing, or from which they are flying away. The servants never cease shoving the chairs to and fro with a harsh screeching noise over the floor, so that one can scarce hear his neighbor speak… the heated, muggy rooms, not to speak of the great abominableness of the passages and halls, despite a most liberal provision of spittoons, conduce to render these institutions by no means agreeable to a European.

March 27, 1861

[The State Department] is a very humble — in fact, dingy — mansion, two stories high, and situated at the end of the magnificent line of colonnade in white marble, called the Treasury, which is here-after to do duty as the head-quarters of nearly all the public departments. People familiar with Downing Street, however, cannot object to the dinginess... A flight of steps leads to the hall-door, on which an announcement in writing is affixed, to indicated the days of reception for the various classes of persons who have business with the Secretary of State; in the hall, on the right and left, are small rooms, with the names of the different officers on the doors — most of them persons of importance; half-way in the hall a flight of stairs conducts us to a similar corridor, rather dark, with doors on each side opening into the bueaux of the chief clerks...

The Navy Yard is surrounded by high brick walls; in the gateway stood two sentries in dark blue tunics, yellow facings, with eagle buttons, brightly polished arms, and white Berlin gloves, wearing a cap something like a French kepi, all very clean and creditable. Inside are some few trophies of guns taken from us at Yorktown, and from the Mexicans in the land of Cortez. The interior enclosure is surrounded by red brick houses, and stores and magazines, picked out with white stone; and two or three green glass-plots, fencing in by pillars and chains and bordered by trees, give an air of agreeable freshness to the place. Close to the river are the workshops: of course there is smoke and noise of steam and machinery...

Sources:

Russell, William Howard, 1820-1907, Diary of William Howard Russell, March, 1861, in My Diary North and South. : T.O.H.P. Burnham, 1863, pp. 602.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)