Nelson Mandela's First Visit to Washington

Nelson Mandela, who died December 5, 2013, was mourned worldwide as the leader who beat Apartheid and then worked to promote reconciliation and racial tolerance in South Africa. But 30 years ago, just months after he was freed from a South African prison, Mandela created a sensation--and some tense, discomforting moments--when he visited the U.S. and met with then-President George H. W. Bush at the White House.

The genesis of Mandela's visit was in February 1990, when Bush telephoned the African National Congress leader to congratulate him on his release after 27 years of captivity. Bush went on to invite Mandela to visit the White House. Mandela responded that he hoped to accept, but that he would have to consult with advisers. His reservations may have been prompted by tensions over a previous, separate phone conversation with then-South African President Frederik W. de Klerk, Bush had invited the leader of the Apartheid regime to visit Washington as well. That move irked many U.S. civil rights activists such as Jesse Jackson and Coretta Scott King, who felt that dismantling Apartheid and releasing the rest of the regime's political prisoners should have been a prerequisite for such an invitation.

Initially, both leaders accepted invitations to visit the White House separately. De Klerk was tenatively scheduled to come to Washington on June 18, the first-ever state visit by a South African leader. Mandela was scheduled to visit second, a week later, which to some seemed to be a slight. But on May 30, de Klerk announced that he was postponing his visit because of the controversy.

Thus, on June 24, a jet from the now-defunct Trump Airlines touched down at National Airport in Washington, and out stepped Mandela, accompanied by his then-wife, Winnie. Just a few days before, Mandela had been cheered on by 500,000 New Yorkers in a tickertape parade, but the reception in DC was much smaller and more low-key. As the Washington Post described the scene, Mandela was welcomed by a 10-person receiving line that included then-D.C. Mayor Marion Barry and his wife Effi, and a crowd of well-wishers waving red, black and gold ANC flags. Mandela stayed at the Madison Hotel, where he met with jounalists and had a gathering with about 200 South African exiles that was closed to the press.

The next day, Mandela went to the White House, for an event that went less than smoothly. The only spectators at the traditional welcoming ceremony were about 200 government employees, but as the Washington Post reported, the usual somber decorum at such events gave way to cheering, as the government staffers called out to Mandela and his wife, imploring them to mingle with the crowd. They took a few steps in that direction, before First Lady Barbara Bush intervened to keep the event on track by approaching and semi-embracing Winnie Mandela.

From a small platform on the South Lawn, President Bush gave remarks in which he condemned Apartheid as "repugnant, but evoked the memory of Martin Luther King, Jr. in calling for an end to the armed struggle against the South African regime, and praised de Klerk for taking what Bush saw as positive steps to end racial repression. That apparently didn't sit well with Mandela, who watched impassively. When it was his turn to speak, he firmly rebuffed Bush, suggesting that the U.S. President was misinformed "due to the fact that he has not as yet got a proper briefing from us."

The two leaders then met for several hours with Secretary of State James Baker and other administration officials. In what reportedly were tense discussions, the ANC leader reportedly pressed for sanctions to remain in place against the Apartheid regime, and sought $10 million in aid to help promote the develoment of democratic institutions in his country.

Two decades later, though, Bush recalled the event more positively in a Huffington Post blog. "We talked about how we shared the goal of true democracy and dismantling, once and for all, the vestiges of apartheid -- a system that based the rights and freedoms of citizenship on the color of one's skin," the former President wrote.

From C-Span, here's a video clip of Mandela's press conference at the Madison Hotel that day.

That evening, Mandela had dinner in the Russell office building with a group of U.S. Senators, anti-Apartheid activists and journalists. Though the entire Senate was invited, only about 40 members showed up. In his remarks, Mandela noted that he had been inspired by an American--not King, but boxer Joe Louis, the African-American heavyweight champ from the 1930s and 1940s. Mandela, himself a boxer in his youth, saw Lewis as proof "that a black man could rise to the top of his field in the profession he had chosen."

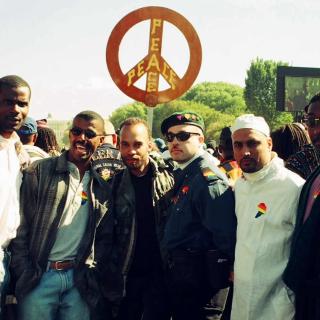

It wasn't until the last day of Mandela's visit that ordinary Washingtonians really got a good look at him. He started the morning with what the Post described as "a brisk two-and-a-half-mile walk" in the neighborhood surrounding his hotel. At mid-day, after addressing a joint session of Congress, Mandela's motorcade roared past Freedom Plaza between 13th and 14th streets. About 20,000 people had gathered for a rally in Mandela's honor in the plaza, and even though he disappointed them by not stopping, they nevertheless chanted his name, and strung a banner welcoming him across the District Building. That afternoon and evening, thousands more waited in line--some as long as six hours--for a chance to cheer Mandela in the only public event of his visit, a televised rally at the Washington Convention Center. After a program that included a performance by a local youth chorus, Mandela finally took the stage at 10 p.m. to tumultuous applause. On the floor and in the upper stands, hundreds of onlookers did the South African toi-toi dance, as the anti-Apartheid leader watched and smiled. "When we finally leave your shores, we shall do so fortified by the magnitude of your love, the greatness of your heart," he told the crowd.

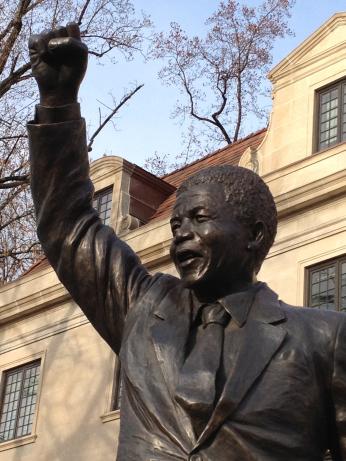

Mandela would return to Washington for several more visits. In September, a 10-foot-tall statue of him, created by sculpter Jean Doyle, was unveiled outside the South African embassy at 3051 Massachusetts Ave. NW.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)