The Capitol Crawl Demonstration Helped Pass the ADA

“I’ll take all night if I have to!” said 8-year old Jennifer Keelan-Chaffins.[1] The second-grader from Colorado wasn’t talking about working on a lengthy homework assignment or completing another video game level. No, she was telling the crowd of reporters that she would not give up as she climbed to the top of the Capitol steps. Diagnosed with cerebral palsy at age two, Jennifer was hauling her body, under the hot Washington sun up, to the Capitol’s front door using only her elbows and knees.[2] Next to her were activists from groups like Denver’s Americans Disabled for Accessible Public Transit (ADAPT) who had thrown aside their wheelchairs and canes to climb in a powerful demonstration for civil rights.

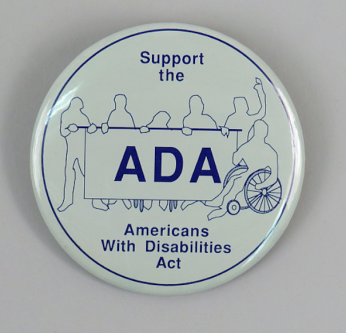

In the Spring of 1990, the disabled community anxiously awaited the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Designed to legally ban discrimination based on physical or mental disabilities, the bill would require that all buildings, transportation, and communication systems be made accessible and provide reasonable accomodations.[3]

In comparison to previous legislation like Section 504 of the 1973 Rehabilitation Act which only applied to recipients of federal funds, the ADA was a sweeping civil rights legislation that would permeate the private sector and mainstream commercial life. Once passed, disabled Americans could access greater opportunities for employment, independence, and travel as well as the freedom to benefit from services offered at restaurants, movie theaters, and medical offices.

Passed in the Senate in September 1989, the ADA appeared to have widespread bipartisan support. However, advocates began to doubt Congress’ commitment to the bill when the legislative process came to an abrupt halt in the House of Representatives. The delay worried activists who began to hear that representatives were proposing amendments that would effectively weaken the legislation.[4]

Most of the pushback came from those concerned about the ADA’s effect on small businesses. Some argued that the proposed changes for accessibility would be too large of a burden for local economies and argued that transportation systems lacked the budget to universally update mass transit to accommodate wheelchairs.[5] Lawmakers like Senator Gordon J. Humphrey claimed that, “rather than merely prohibiting discrimination against the disabled, the bill compels employers to make significant expenditures and extensive physical alterations to their facilities to accommodate an unlimited variety of job applicants.”[6]

In response, ADA supporter Rep. Major R. Owens argued that the Congress’ postponement was a dangerous strategy that threatened to limit the bill’s scope and continue to keep the disabled community segregated from mainstream society. Owens bluntly told reporters that, “all the i's have been dotted and all the t's have been crossed. There have been enough negotiations — delay is the real enemy.”[7]

Tired of waiting, activists from across the country took matters into their own hands and descended upon D.C. in protest. On March 12, 1990 a diverse crowd of about 1,000 demonstrators convened in front of the White House and began chanting their slogans for civil rights as they marched and rolled along Pennsylvania Avenue to the Capitol.[8] Calling their rally “The Wheels of Justice”, ADAPT activists gave emotional speeches to energize the crowd as they blocked traffic on busy streets.

The protesters did not let up as the afternoon wore on. Impassioned and inspired, some decided to throw their crutches and wheelchairs to the ground. As they laid on the stone pavement in front of the Capitol Building, the demonstrators harnessed the strength to hoist their bodies up and slowly but surely drag themselves step by step along the Capitol’s staircase.[9] Protester Bob Kafka traveled from Austin, Texas to participate in the demonstration and told the reporters during his slow journey up the marble steps:

“Too often disabled people are seen as objects of charity or pity. We're here to change that image. And we're here to send a message to the President and to Congress that this bill needs to be passed with no weakening amendments.”[10]

And boy did they change that image. Policy expert, Lex Frieden who worked on crafting the ADA rcounded that, “I think on that day and at that time, more people learned about disability discrimination and equal opportunity than we can imagine.”[11] Using only their forearms or rolling on their backs, resilient participants as young as Jennifer Keelan-Chaffins strikingly highlighted the injustices of inaccessibile architecture and the necessity of solidifying the ADA into law. Paulette Patterson was out of breath as she slid up the steps, but took a few seconds to tell reporters, “I want my civil rights. I want to be treated like a human being.”[12]

Some local Washingtonians stumbled upon the protest and were eager to learn more about the movement. However, they were disappointed to find that the city’s newspapers were not covering the “Capitol Crawl” effectively, if at all. D.C. resident Earl Shoop wrote to the Washington Post saying that locals were looking for more information but, “if they depended on The Post to find out, they are still wondering. Certainly, the issue of civil rights should rate in-depth coverage...but The Post apparently didn't consider the event newsworthy for I could find no coverage at all in the March 13 paper.”[13]

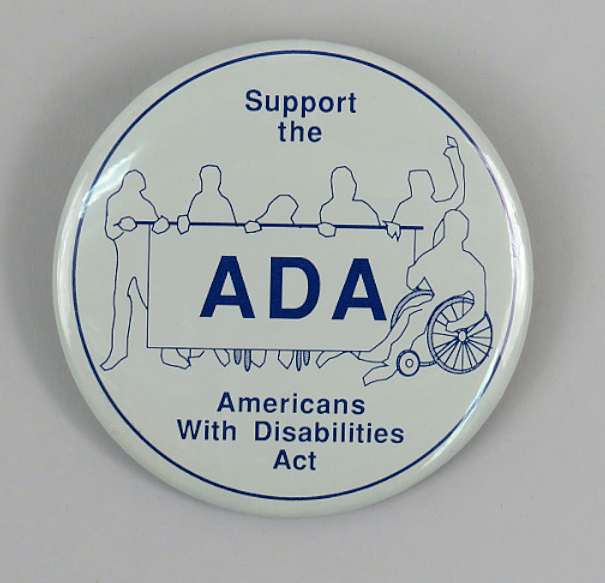

Whether the world was watching or not, by the end of the day the energy was still high among the protestors. Filled with resolve to see the ADA ratified, I. King Jordan, the first deaf President of Gallaudet University, summed up the crowd’s sentiment saying: “If we have to come back, perhaps we'll simply stay until they pass [the bill].”[14]

True to their word, over 100 protesters returned the next day demanding that the House of Representatives uphold their rights.[15] This time, however, they didn’t stop at the steps. Determined to stage a sit-in until the ADA was passed, the crowd made their way into the Capitol Rotunda and came face to face with House Speaker Thomas Foley and House Minority Leader Robert Michel. The decision to occupy the Capitol was inspired by the work of black Civil Rights activists as described by organizer Wade Blank who said, “we're taking the strategies of the 60's that helped get rights for black and brown people and women, and using them for people with disabilities.”[16]

Intent on making a commotion to prompt swift action in Congress, protesters chanted “Access is a civil right!” and “The people united will never be defeated!”, cries that echoed loudly in the cavernous Rotunda.[17] The representatives tried to reassure those gathered that “it [was] a priority for passage in this session of the Congress” however when asked by an activist “will it be on the floor in 24 hours?” Foley admitted that the delay would continue, causing an uproar of boos and catcalls.[18]

Unsure as to how to respond to the protest, arrests began once Capitol Police Officer G.T. Nevitt announced that the demonstrators were being charged with unlawful entry.[19] However, the demonstrators were not going to leave without a fight. Some threw themselves on the ground while others bound their wheelchairs together with chains.

The Capitol police, dressed in full riot gear, used chain cutters to break the links and strapped individuals to their wheelchairs as they carried each protester out of the Capitol one at a time in a process that took two hours.[20] The second day of lobbying ended dramatically, but left a lasting impression. Disabled Americans made it clear that they would not disappear or be pushed aside and after March 13, the ADA solidified its place in the Congressional agenda.

By July 1990, the ADA was finally approved in both the Senate and the House. Passing 91-6 in the Senate and 377-28 in the House, elected officials spoke with emotion as they acknowledged the impact the bill would have on members of their own families.[21] Senator Tom Harkin, a prominent supporter of the ADA made his comments in American Sign Language (ASL) in honor of his deaf brother, expressing to his colleagues:

“Today, Congress opens the doors to all Americans with disabilities. Today we say no to ignorance, no to fear, no to prejudice.”[22]

Gathered in wheelchairs outside the Senate reception room, activists celebrated when a security guard announced the good news. Pat Wright, the Director of the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund joyfully exclaimed, “no longer will people with disabilities be second-class citizens.”[23] The ADA’s journey in Congress had come to a close, but the legislation still had one final stop to make...the White House.

On July 26, 1990 President George H.W. Bush signed the ADA into law. Over 2,000 activists gathered on the South Lawn and watched the final signatures land on the bill that they had fought so tirelessly for.[24] Over 43 million Americans would benefit from the legislation that would radically transform the country. Received by the crowd with jubilant cheers and tears of joy, President Bush addressed the nation declaring, “let the shameful wall of exclusion finally come tumbling down.”[25]

Since its signing, the ADA has profoundly changed the country. Things we take for granted in our everyday lives from ramps to curb cuts to warning tiles on train platforms to automatic doors, all came as a result of the advocacy of the fearless protesters of the Disability Rights Movement. The New York Times succinctly summarized the impact of the ADA stating, “the act does more than enlarge the independence of disabled Americans. It enlarges civil rights, and humanity, for all Americans.”[26]

Footnotes

- ^ William M. Welch, “Disabled Climb Capitol Steps To Plea For Government Protection,” Associated Press, March 12, 1990.

- ^ William J. Eaton, “Disabled Persons Rally, Crawl Up Capitol Steps Congress: Scores Protest Delays in Passage of Rights Legislation. The Logjam in the House Is Expected to Break Soon,” Los Angeles Times, March 13, 1990.

- ^ Steven A. Holmes, “Measure Barring Discrimination Against Disabled Runs Into Snag,” New York Times, March 13, 1990.

- ^ Frank Wolfe and Sonsyrea Tate, “Disabled Occupy House Offices; 59 Are Arrested,” The Washington Times, March 15, 1990.

- ^ Wolfe and Tate.

- ^ Steven A. Holmes, “Rights Bill for Disabled Is Sent to Bush,” New York Times, July 14, 1990.

- ^ Eaton, “Disabled Persons Rally, Crawl Up Capitol Steps Congress: Scores Protest Delays in Passage of Rights Legislation. The Logjam in the House Is Expected to Break Soon,” Los Angeles Times, March 13, 1990.

- ^ Welch, “Disabled Climb Capitol Steps To Plea For Government Protection,” Associated Press, March 12, 1990.

- ^ Eaton, “Disabled Persons Rally, Crawl Up Capitol Steps Congress: Scores Protest Delays in Passage of Rights Legislation. The Logjam in the House Is Expected to Break Soon,” Los Angeles Times, March 13, 1990.

- ^ Holmes, “Measure Barring Discrimination Against Disabled Runs Into Snag,” New York Times, March 13, 1990.

- ^ Julia Carmel, “15 Moments Within the Fight for Disability Rights,” New York Times, July 26, 2020.

- ^ Eaton, “Disabled Persons Rally, Crawl Up Capitol Steps Congress: Scores Protest Delays in Passage of Rights Legislation. The Logjam in the House Is Expected to Break Soon,” Los Angeles Times, March 13, 1990.

- ^ Earl Shoop, “Where Was the Coverage?,” The Washington Post, March 24, 1990.

- ^ Eaton, “Disabled Persons Rally, Crawl Up Capitol Steps Congress: Scores Protest Delays in Passage of Rights Legislation. The Logjam in the House Is Expected to Break Soon,” Los Angeles Times, March 13, 1990.

- ^ Eric Anderson, “Springs People Are Arrested in D.C. Protest,” Colorado Springs Gazette - Telegraph, March 14, 1990.

- ^ Steven A. Holmes, “Disabled Protest And Are Arrested,” New York Times, March 14, 1990.

- ^ Holmes, “Disabled Protest And Are Arrested.”

- ^ “Handicapped Protesters Arrested,” The Washington Times, March 14, 1990.

- ^ “Handicapped Protesters Arrested.”

- ^ “Protest Arrests,” Orlando Sentinel, March 14, 1990.

- ^ Helen Dewar, “Senate Approves Disabled Rights Bill: Bush Expected to Sign Landmark Legislation,” The Washington Post, July 14, 1990.

- ^ Holmes, “Rights Bill for Disabled Is Sent to Bush.” New York Times, July 14, 1990.

- ^ Holmes, “Rights Bill for Disabled Is Sent to Bush.”

- ^ “A Law for Every American,” New York Times, July 27, 1990.

- ^ Ann Devroy, “In Emotion-Filled Ceremony, Bush Signs Rights Law For America’s Disabled,” The Washington Post, July 27, 1990.

- ^ “A Law for Every American,” New York Times, July 27, 1990.

![504 Button Bright yellow protest button created by the American Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities (ACCD). The pin reads in black block-lettering: "Handicapped Human Rights, Sign 504, ACCD." [Source: National Museum of American History]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/504%20Button.jpeg?itok=yiaSjVx2)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)