Arlington's First Official Unknown Soldier

At Arlington National Cemetery, one of the most haunting features is the Tomb of the Unknowns, also known as the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. (The memorial never has been officially named, so either name works.) The white marble sarcophagus has a flat-faced form with neoclassical columns set into the surface, and is emblazoned with three Greek figures representing Peace, Victory and Valor, along with six wreaths.

On the rear of the monument, there's a haunting inscription: Here rests in honored glory, an American soldier known but to God.

But the story of how the first official unknown soldier from World War I was selected for burial in the graves alongside the monument is a strange one. For one, he wasn't actually the first unidentified casualty to be entombed at Arlington, which was created from the confiscated estate of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee. About 2,011 unidentified sets of Civil War remains were buried there starting in 1865, in a simple pit, 20 feet deep, that was dug inside what had been the flower garden of the general's wife, Mary Lee. (As historian George W. Dodge notes, Mrs. Lee was not too happy about that, and complained after an 1866 visit that "they have done everything to debase and desecrate" the Lees' former property.

In 1866, a granite sarcophagus was dedicated at Arlington to honor the bodies of 2,011 unidentified Civil War casualties. An 1873 Associated Press dispatch describes a particularly moving service on Decoration Day (now Memorial Day), led by President Ulysses S. Grant, in which mourners gathered around the sarcophagus as orphans from the National Soldiers' and Sailors' Home sang a hymn, and a war veteran named J.P. Irvine recited a poem entitled "Unknown," the words of which unfortunately seem to have vanished into the mists of history.

After World War I, the idea of selecting a single unknown soldier for honors gained currency, in part because the British and the French had decided to do it. U.S. Rep. Hamilton Fish, Jr. of New York convinced Congress to pass a resolution calling for the U.S. military to retrieve the remains of an unidentified U.S. soldier from Europe and bury him in a new tomb in Arlington near the cemetery's amphitheater, where a new, more elaborate monument also would be built. ish wanted a body in time to hold an elaborate memorial service on the traditional May 30 Decoration Day.

But according to a U.S. Army historical account, officials at the War Department, the forerunner of today's Department of Defense, weren't so thrilled with the idea. As then-War Secretary Newton D. Baker told a Senate committee considering the legislation, while 1,237 American dead were still unidentified, the military was hopeful that it eventually would be able to put a name on them all, and was reluctant to hastily select and bury an "unknown" soldier who might later be identified. After Baker was replaced by a new War Secretary, John W. Weeks, he voiced similar objections, but instead suggested that one might be found by Nov. 11, the date of the armistice that ended the war. In response, Congress agreed to make Nov. 11 a national holiday for honoring World War I dead.

Military officials still had the problem of finding a soldier whose remains were unlikely ever to be identified. In September 1921, the War Department ordered a Quartermaster Corps team to select a body from those buried in French graveyards. After examining the paperwork connected with the buried dead, they selected four bodies to be exhumed--one each from Aisne-Maine, Meuse-Argonne, Somme, and St. Mihiel cemeteries--as possible recipients of the honor. (They also were poised to dig up another four alternates, if none of those worked out.) In October, all four were transported by truck to the city hall of Chalons-sur-Marne for an induction ceremony in which one of the bodies would be chosen for burial in the Arlington tomb.

Since maintaining the mystery was crucial at that point, U.S. and French soldiers rearranged the caskets, so that it would be difficult even to tell which cemetery each of the bodies had come from. Originally, an officer was to pick the honoree, but after American officials found out that the French had designated an enlisted man to pick their own unknown soldier, they did the same, and left the selection to a Sgt. Edward F. Younger. As a band played a hymn, Younger walked around the caskets several times, and then randomly placed roses on one of the lids. The body inside was then transferred into a special, more elaborate casket, which was sealed for shipment to the U.S. The other three also-rans were then shipped by truck to a cemetery outside Paris, where they were reburied.

On Nov. 9, 1921, the U.S.S. Olympia sailed up the Potomac River, receiving and returning salutes from military posts along the route, and docked at the Washington Navy Yard. There, a contingent of dignitaries, including General of the Armies John J. Pershing and War Secretary Weeks, were on hand to meet the casket and watch it placed on a caisson. The procession, escorted by two squadrons of horse cavalry, then proceeded via M Street and New Jersey Avenue to the Capitol, where the casket was taken into the rotunda to lie in state. President Warren Harding and his wife then paid their respects, with Mrs. Harding placing a wide white band of ribbon, which she had made herself, on the casket.

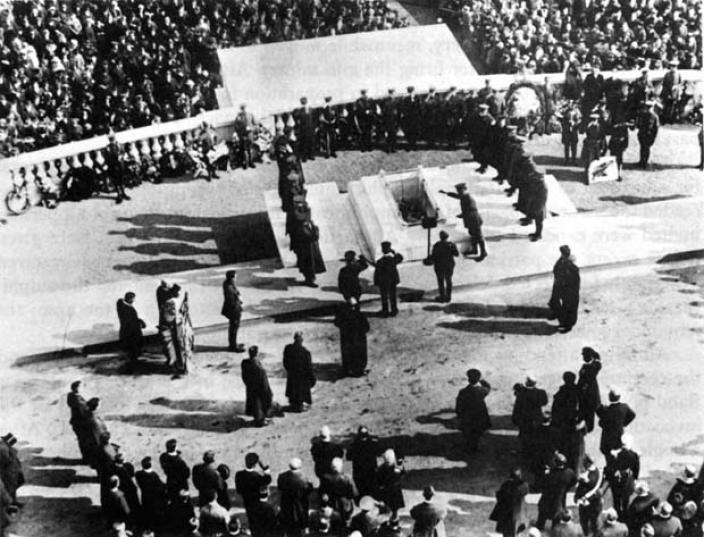

Two days later, an even more elaborate funeral procession that included a regiment of marching infantry, a band, a drum corps, and cavalry and artillery squadrons, the casket was transported down along Pennsylvania Avenue to 15th Street, on 15th Street to Pennsylvania Avenue again, past the White House to M Street, then on M Street to Aqueduct Bridge (slightly upstream from the present-day Francis Scott Key Bridge). Three hours later, the parade reached Arlington cemetery, and the casket was carried inside the amphitheater. President Harding addressed a crowd of more than 5,000 people, giving a speech in which he pleaded for an end to war. Then, various dignitaries, including Congressman Fish, paid their respects and laid wreaths. Perhaps the most unusual tribute came from Chief Plenty Coups of the Crow nation, who laid his war bonnet and coup stick at the tomb.

Then, the casket finally was lowered into the crypt, the bottom of which had been covered with a layer of soil from France. A battery fired 21 guns in salute, and a bugler played taps.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)