How "Schneider's Folly" Became D.C.'s Most Exotic Landmark

One of the things that helps make Washington's vistas so grand--but continually frustrates developers and architects--is the district's Congressionally-imposed 115-year-long ban on skyscrapers. Congress passed the 1899 Height of Buildings Act, and then modified the law in 1910, creating a complex set of restrictions based on location and street width. As a result, the tallest commercial-residential structure in the city is the 12-story, 210-foot-tall One Franklin Square building on K Street NW, completed in 1989, which is dwarfed by the towers that dominate the skylines of many other big U.S. cities. Despite complaints that the ban has inflated office rents and limited affordable housing, it has withstood the test of time. Last November, in fact, the National Capital Planning Commission, a federal agency that controls development in the District, rejected changes that might have allowed sightly taller buildings in some areas of Washington.

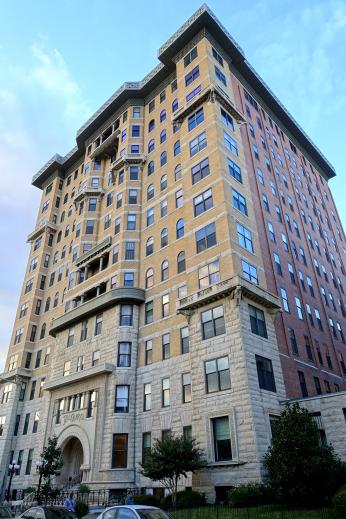

It might seem intuitive that the skyscraper ban was imposed to protect views of the U.S. Capitol and the Washington Monument. But oddly, Congress was prompted to restrict construction heights because of Dupont Circle residents' griping about being overshadowed by what today is regarded as one of the District's architectural treasures--The Cairo apartments at 1615 Q Street NW, which is honored in the National Register of Historic Places. The 12, story, 164-foot-tall brick structure, is hailed in the National Register as a prime example of Moorish Revival or Neo-Moorish architecture, a movement popular in from the mid-1880s to the early 1990s in Europe and the U.S., evoked the Muslim architecture of pre-1492 Spain. That theme can be seen in the building's elegant archways and columns, and its exotic decorative flourishes, such as elephant head carvingsover the first-story windowsills and what the National Register describes as "eagle-like gargoyles" that were possibly inspired by the Patio of the Lions in the Alhambra, a mid-1300s landmark in Granada, Spain. At the time of its completion in 1894, the Cairo also was one of the first steel frame buildings in Washington, and the largest non-government structure built in the nation's capital.

The Cairo was the work of a Washington architect and builder of the late 1800s and early 1900s, Thomas Franklin Schneider, who was known as "the young Napoleon of F Street," in deference to both his ambition and his love of grandeur. That probably was an apt description for someone who erected scores of grand homes in the District, including his own eponymous mansion, Schneider House at 18th and Q Streets NW, a 50-room Romanesque mansion at the present location of the Dupont East condominiums. Between 1888 and 1906, Schneider erected 19 apartment houses in DC, including The Woodley on Columbia Road and The Iowa on Logan Circle. He also built the Forest Inn resort in Forest Glen, Maryland.

But The Cairo would be Schneider's signature piece--and a lightning rod for controversty. In 1893, he attended the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where he saw Louis Sullivan's magnificent Transportation Building, and returned home with the ambition of erecting his own flamboyant masterpiece. He spent a then-princely $425,000--about $11 million in today's dollars-to build The Cairo, a 100-unit luxury hotel. In February 1894, he obtained a building permit from the District's commissioners, and erected The Cairo so rapidly that it was completed by December of that year. The ornate structure quickly attracted attention. A brochure for The Cairo noted that it also relied exclusively upon electricity for artificial interior light--a technological advance that other builders, who were slow to completely abandon the gaslights, hadn't yet embraced. According to a 1906 advertisement, it boasted "the largest rooms of any apartment house in the city," in addition to amenities such as a billiard room and a phone in every apartment.

Nevertheless, Schneider's fellow architects didn't think too highly of his new building. The Cairo was the subject of a nasty review in the presitigous publication Architectural Record, which derided the building as a "revolting notion" that was not an offense against taste but flimsily designed as well. But most of all, interestingly, the publication thought it was absurd that anyone would erect a private building of that size in Washington, which the architectural aesthetes of the time apparently saw as Podunk compared to metropolises such as New York and Chicago. "A twelve-story apartment house in Washington is gratuitous and inexcusible, and denotes a deeper dye of depravity than it would in a more crowded city, where land is not to be had," the Record railed.

That scathing denunciation probably only increased the ire of angry Dupont residents, who complained that it was out of scale with the rest of the neighborhood, and blocked their views and left them in its shadows. Additionally, even though the building had been advertised as fireproof because of its steel frame, neighbors worried that it might turn into an inferno, because District firefighters didn't have ladders capable of reaching the top floors. Some even feared that The Cairo would fall over in a strong wind, prompting District officials to conduct tests to make sure the structure was solid. The outcry, nevertheless, didn't subside, and Congress eventually caught enough of the heat to step in and enact building height limitations five years after the Cairo was built.

Despite that bad publicity, The Cairo proved to attract plenty of long-term tenants--including Schneider himself, who abandoned his own mansion to move in--and also visitors such as F. Scott Fitzgerald and Thomas Edison. Another illustrious patron, Queen Liliuokalani, the deposed monarch of Hawaii, stayed there when she visited Washington in a fruitless effort to regain her throne in 1897.

Schneider continued to work as an architect until the 1920s, when he retired to a house that he had designed for himself on the edge of Rock Creek Park. After his death in 1938, the building's ownership passed to his daughters, who sold in in 1958 for $3 million. After that, according to a 2003 Metro Weekly article, the building gradually fell into a long period of decline, and Schneider's once-grand palace became a flophouse peopled by squatters, drug dealers and pimps, while its grand ballroom became a venue for clandestine drag shows. Eventually, however, the building was rehabilitated, and despite suffering damage in a 2007 fire, today again is an upscale residence. Architectural historian G. Martin Moeller, Jr., describes it as "one of Washington's guilty architectural pleasures."

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)