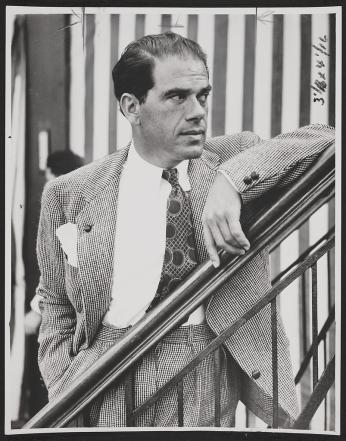

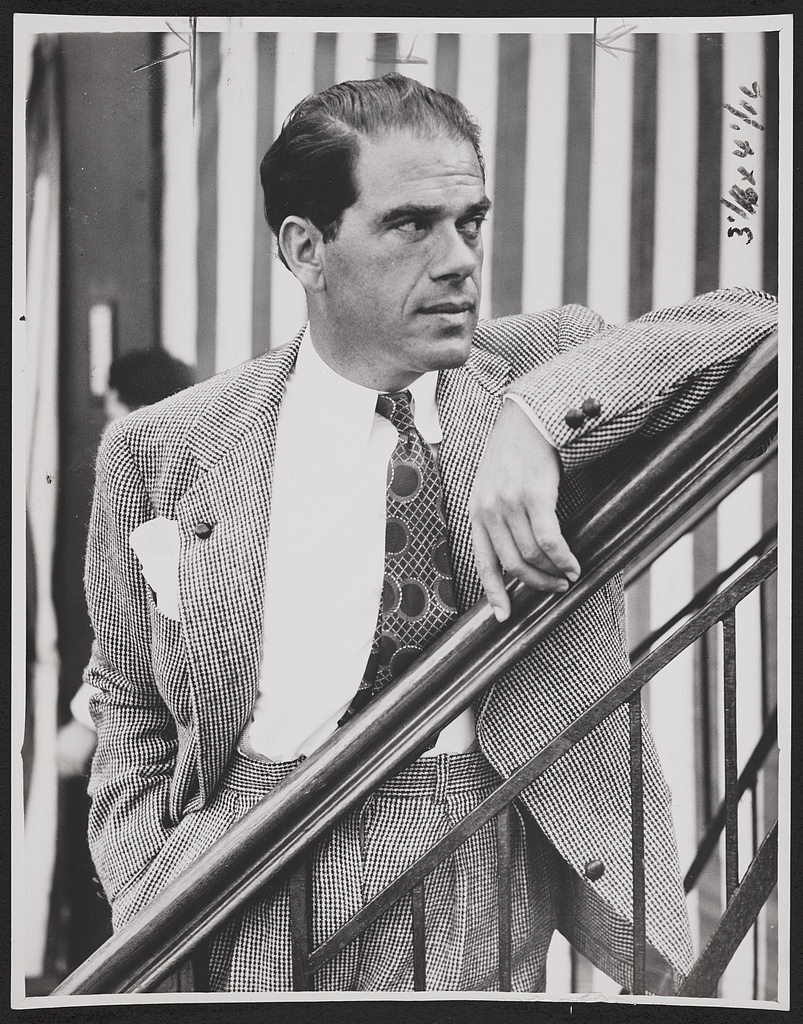

How Frank Capra Aroused Washington's Ire

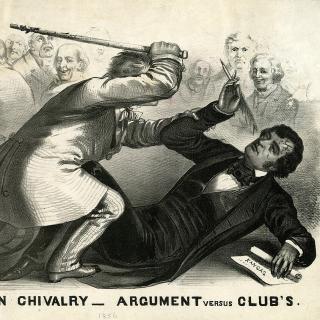

Director Frank Capra's classic 1939 film, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, a comedy-drama about an ordinary citizen who ascends to the U.S. Senate, today is widely regarded as an uplifting, if overly sentimental, tribute to the egalitarianism at the heart of American-style democracy. But when it was released, Mr. Smith wasn't regarded as a feel-good film by members of Congress. Though Capra's depiction of a Capitol Hill ruled by corrupt, cynical dealmakers was vastly tamer than the blackmailing, murderous libertines in the current hit Netflix series House of Cards, it seemed utterly scandalous to legislators of the day, who vehemently denounced the film and sought to punish Hollywood for daring to make it.

Capra, who himself described Mr. Smith as "a very mild motion picture" and claimed the goal was to "idealize American democracy, not attack it," clearly didn't set out to create such a controversy when he began working on the project in 1938. As he recalled in his 1971 memoir, he simply loved the two-page synopsis of an original story by Lewis R. Foster, a silent movie director who went on to greater fame as a screenwriter. Capra was eager to repeat his smash 1936 success Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, and his assistants pitched Mr. Smith to him as a perfect vehicle for that movie's stars, Gary Cooper and Jean Arthur. "Buy it, Quick!" Capra recalled saying. (In the director's version of events, he immediately envisioned Jimmy Stewart instead of Cooper in the lead role, but Capra biographer Joseph McBride notes that when the project was first announced that summer, Cooper's name was still associated with it in press reports, and Stewart wasn't announced as the star until January 1939.)

That October, according to McBride, Capra and his screenwriter, Sidney Buchman, went to Washington to do research for the film. They toured the District by bus and visited the Lincoln Memorial — something their protagonist, Jefferson Smith (portrayed by Stewart), also does in the film. They even arranged to attend a press conference in the Oval Office, standing in the back row as reporters clustered around President Franklin D. Roosevelt's desk. Capra was too short to see over the journalists' heads as they asked questions about Hitler and the Munich agreement to partition Czechoslovakia. Capra did manage to catch a brief glimpse of FDR, sitting in a high-back chair. "A long cigarette holder tilted up rakishly from his massive face as he scanned the reporters with a roguish, challenging smile," wrote Capra, who was so startled by the President's seeming physical vigor that he momentarily wondered if he actually was crippled by polio. Though Capra disapproved of FDR's policies — voting for Wendell Willkie in 1940 — he nevertheless came away deeply impressed with FDR's stage presence.

Capra also visited FBI headquarters, where he was allowed to fire a submachine gun on the bureau's shooting range. Then-FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover had a photograph of that experience delivered to Capra's suite at the Mayflower Hotel. There was a certain irony to the ferociously anti-Red Hoover extending that gesture since Capra's film was being written by Buchman, a then-active member of the communist party who years later would be subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee and blacklisted for refusing to name names.

According to film historian Daniel Eagan, Capra later returned to Washington with a film crew to do some outdoor location shots. But most of Mr. Smith was shot on the Columbia lot back in California, where carpenters built a full-scale model of the U.S. Senate chamber that was exacting in its details, thanks to the help of Capra's technical advisor James D. Preston, a former superintendent of the Senate press gallery.

In April 1939, Capra began principal photography. Moving tons of equipment around in the imitation Senate chamber, a four-sided, multi-level set filled with hundreds of extras and technicians, was a logistical nightmare for the cameramen and sound crew. So instead of the single-camera approach that was customary at the time, Capra tried a then-novel approach of using multiple cameras, which also enabled him to shoot entire scenes without pausing for closeups. Without that innovation, Capra later recalled, "we might still be there." He also perfected the trick of using the original soundtrack of the scenes to feed the actors lines for their off-set closeups, rather than have someone read the script to them. Even so, he still ran a week over schedule and $300,000 over budget.

That autumn, Capra brought the film to Washington for an Oct. 17 preview at Constitution Hall. The Washington Post excitedly billed the event as the "world premiere" and noted, incorrectly, that "many scenes" had been filmed in Washington. The old Washington Times-Herald actually printed a special edition, with the premiere as its front-page story. The event was attended by 4,000 guests, including Senate Majority Leader Alben W. Barkley, Speaker of the House William Bankhead and Majority Leader Sam Rayburn, and 44 other senators and 250 representatives. FDR's Attorney General Frank Murphy and Postmaster General Jim Farley also were in attendance, as were several members of the U.S. Supreme Court. In addition to the Washington press corps, reporters and columnists from New York, including big names such as Walter Winchell and Dorthy Kilgallen, also came in for the event. Columbia Pictures sent a delegation of executives, though the film's stars, Stewart and Jean Arthur, didn't make it. (Stewart was busy filming Destry Rides Again.)

That evening, the crowd was serenaded by a Marine Corps band playing that service's hymn and other patriotic songs. Capra sat in a box with Sen. Burton K, Wheeler of Montana, and his wife and daughter. As the opening credits appeared on the screen, the director got a case of nerves. "I crossed all my fingers and prayed a little that nothing would go wrong," he later recalled.

But it did. About 20 minutes into the film, during a scene between Stewart and Arthur, their voices abruptly speeded up. Capra instantly knew that the film in the projector had jumped a sprocket wheel. He jumped up out of his seat and searched frantically for the upstairs projection room. After climbing up a ladder, the director found himself out in the nighttime darkness, dampened by a misty rain, until he spotted the glow of the booth, which had been built into the hall's roof. He ran along a catwalk and bumped his head on overhanging pipes. Finally, Capra flung open the door, startling the projectionist, who told the director to back off. "Keep your shirt on, Mac," he warned in a raspy voice. "I got it, I got it."

Thus chastened, a soggy Capra returned to his seat inside the hall, his skull still throbbing from his encounter with the pipe. But according to his account, the director soon had a bigger headache. When Stewart's character Jefferson Smith started his famous filibuster in a fruitless effort to prevent a corrupt dam-building scheme, Capra recalled, Sen. Wheeler's wife and daughter began giving him hostile stares and whispering in the senator's ear. He also noticed dignitaries getting up and moving to the exits. "By the time Mr. Smith sputtered to the end music, about one-third of Washington's finest had left," Capra later wrote. "Of those who remained, some applauded, some laughed, but most pressed grimly for the doors." Even Sen. Wheeler, who had stayed, left huffily with a curt, over-the-shoulder "Good evening," Capra recalled.

Capra biographer McBride says the director exaggerated the negative ambiance a bit, noting that press accounts of the event don't describe any walkouts. But he writes that members of the Senate and the press corps looked noticeably frazzled, "as if they'd been through a tough session with a traffic cop."

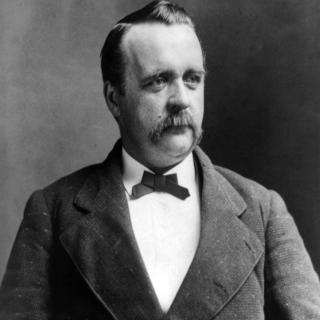

Either way, though, it soon became obvious that Washington politicians hated Mr. Smith. Majority Leader Barkley denounced the movie in an interview, calling it a "grotesque distortion" of the way the Senate is run. "It showed the Senate as the biggest aggregation of nincompoops on record," he ranted, adding that "I did not hear a single Senator praise it." Another senator, James F. Byrnes from South Carolina, complained that Capra's film turned Congress into a mockery "that dictators of totalitarian governments would like to have their subjects believe exists in a democracy." Joseph P. Kennedy, the U.S. ambassador to England (and father of future President John F. Kennedy), sent a telegram to Harry Cohn at Columbia pictures, urging the studio to withdraw the film from distribution overseas, lest it harm U.S. prestige as war erupted in Europe.

What was even scarier for Hollywood: Members of Congress also made noises about reviving legislation to ban studios from compelling theater owners to rent multi-movie "blocks," a practice that forced the latter to accept several stinkers in order to get a hit film. (Eventually, the studios were pressured into a federal consent decree in 1940 that put limits on the practice, and it finally died when the U.S. Supreme Court demolished the old studio system with U.S. v. Paramount in 1948.)

The brouhaha over Mr. Smith gradually died down, and the film went on to receive 11 Oscar nominations. But the competition was too strong in a year that also saw classics such as Gone With The Wind, Goodbye Mr. Chips, Stagecoach, and The Wizard of Oz, and in the end, the film's only statuette went to Foster for best original story. Nevertheless, Mr. Smith has continued to resonate over the years with audiences disillusioned with politics, and in 1998 American Film Institute put it at no. 29 on its list of the 100 greatest films of the past century.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)