The Police Scandal That Nearly Toppled D.C.’s Government

In July 1886, an insurance executive took command of D.C.’s police department. Commissioned as a major, Samuel Walker was hired to reform law enforcement in Washington, which was known for inefficiency, incompetence, and brutality. Walker was an outsider, but he had a vision. He promoted good officers, demoted poorly-regarded ones, and reshaped the city’s precinct map. He cracked down on on-duty drinking, and put police on notice that violence against civilians would no longer be tolerated. In his budget for 1887, he offered a sweeping proposal for modernization, aspiring to hire 75 new officers and integrate new telephone technology. After four months on the job, Walker started to see results.[1]

Then the rumor got out. Its origins were murky, but by early November, even President Grover Cleveland had heard it. Major Walker had ordered Washington police to spy on members of Congress. His goal? Collect incriminating information that could be used as blackmail to boost the department’s budget.

Over the following weeks, Walker’s supposed order sparked the biggest scandal in the history of Washington policing to that point. Debates over “who said what when” took place everywhere from local taverns to Capitol hallways. Along the way, the affair took on even greater significance. What began as a sensational charge grew into a struggle over the meaning and legitimacy of government in the District of Columbia.

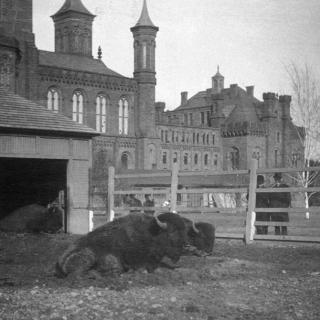

A story of police espionage and blackmail would have made headlines in any U.S. city, but it was particularly loaded in 1880s Washington. In 1874, Congress had abolished democracy in D.C. Officially, the move was a response to a debt crisis caused by Washington’s governor Alexander Shepard, but the underlying motives were racial. As one history of the city put it, Congress and local leaders “wanted to get rid of the negro vote” by eliminating self-government altogether. In its place, Congress created a three-man Board of Commissioners, nominated by the president, to oversee the District. Congressional committees managed Washington’s budget, including funding for its police department. Outside of a few powerful business figures, Washingtonians of all races had little-to-no say in the governance of their city.[2]

Unsurprisingly, Walker’s alleged order stunned the federal officers tasked with running Washington. When Grover Cleveland heard of it, he personally wrote a letter to the D.C. Commission telling them to investigate. Walker told them that he never ordered anyone to spy on Congress. Later that day, he produced a letter signed by every captain and lieutenant in the police department backing him up. But the rumors kept circulating, and the public found them too credible to ignore.[3]

On November 8, Walker struck back. He blamed the scandal on Lt. Richard Arnold, head of the city’s First Precinct. In an open letter, Walker said that Arnold “willfully and falsely” told others that the major had initiated a blackmail scheme, with the intention of “inaugurating a public scandal.” The accusations shocked Washington. Arnold was one of the city’s most popular officers, a friend of notables like department store magnate Isadore Saks and Sen. George Edmunds. Just months earlier, he had been a leading candidate for the position of major, which the commissioners had given to Walker. By all accounts, the two were friendly. Now, they would face off in a trial before the Commission.

The following Saturday, Walker, Arnold, and a bevy of witnesses gathered around a single table in the dingy commission headquarters on Four-and-a-half Street. They all agreed on some basic facts. Lt. Arnold had returned from headquarters one day in October and told his deputy about a remarkable instruction from Major Walker: to “keep a quiet lookout for Congressmen, and whenever any of them were found south of the Avenue, or in places of questionable repute, to make a note of it.” Arnold told no one else, but his deputy shared the supposed order with a disgruntled officer who Walker had demoted. This man seemingly repeated it to half of Washington.[4]

Walker and his allies argued that Arnold had relayed a total falsehood. In the Major’s telling, he had simply encouraged his subordinates to reach out to their friends in Congress on behalf of the department’s budget. Washington was a small town, and most lieutenants had personal connections they could leverage. Recounting the meeting, Walker recalled that Arnold had mentioned that a certain congressman who was often found in the First Precinct’s “bawdy houses” might be easy to sway, but that he rebuked this nod to blackmail. One by one, other lieutenants corroborated Walker’s story.

But in the afternoon, Walker’s narrative collapsed when Lt. John F. Kelly took the stand. Like Arnold, Kelly was a prominent officer, having served since 1861 and possessing friends in high places. Few expected Kelly to support Arnold- the two were rivals who barely spoke to each other.[5] But on the stand, Kelly backed Arnold and quoted Walker as encouraging espionage:

“Any time you gentlemen know anything of that kind about members of Congress, just come quietly to me and report and I think we can get the force increased by a hundred men before Congress adjourns.”

When Arnold testified the next day, he shared an identical story, mentioning that he and Kelly had discussed just how dangerous the idea was after the meeting. The two had signed Walker’s letter denying the existence of the order, but under oath they said that was only to help avoid a public scandal once rumors started circulating.[6]

After hearing from Kelly and Arnold, almost every Washingtonian believed that Major Walker had given the order. Kelly’s testimony was particularly decisive, coming from a reputable man who had no reason to help Arnold. The Washington Post said Walker had “committed a most serious blunder, which, in this case, is equivalent to a crime,” and reluctantly called on him to resign. Congressmen reached a similar conclusion, threatening an investigation if Walker was not dismissed.[7] As the commissioners reviewed the testimony, public speculation went wild. Many suspected that the commissioners themselves had planned the espionage, maybe to secure federal funds to extend Massachusetts Avenue. Their situation was becoming tenuous. As one D.C. official put it, “It is not a question now how they can save Walker, but how the Commissioners can save themselves.”[8]

On November 24, the Board released their judgement. To no surprise, they ruled that there was not enough evidence to convict Lt. Arnold. But that did stop them. They decided that Walker had never issued the espionage order, and that Arnold must therefore have been lying when he discussed it. The Commissioners dismissed him from the force. They did not end there. Because Kelly had supported Arnold, the Commissioners found him liable for perjury and suspended him without pay. They also suspended multiple witnesses who had testified during the trial. As a final coda, they bowed to public opinion and also accepted Major Walker’s offer to resign.[9]

Almost every group in Washington condemned the ruling. Police were furious at the cruel treatment of their most senior, respected members. D.C.’s business community was similarly inflamed. Meanwhile, the Commission suffered in the press. An Washington Critic editorial quipped that “the court could hardly have surprised the public more if it had gone a step further and found itself guilty.” New York newspapers, always eager to poke fun at upstart Washington, went even further. The Tribune called the verdict “laughable, illogical, and unjust” and noted with amusement that “everybody is ridiculing and denouncing it.” [10]

Soon, ridicule turned into action. Supporters of Arnold and Kelly staged a rally at the National Rifles’ Armory near Ford Theatre, where anger at the treatment of the lieutenants morphed into indictments of the District’s form of government. Speakers questioned why, in the face of such an obvious wrong, D.C. residents could not protest at the ballot box like other Americans. In a fiery speech, former congressman J. Hale Sypher called the absence of democracy in Washington an affront to the Constitution that only benefited the rich and connected:

“The extraordinary tribunal not only convicted the accused, but the accuser, the witnesses, and the tribunal itself. The immortal words of Lincoln were that this was ‘A government of the people, by the people, for the people.’ However, I apprehend that in this District it is a government of jobbers, by the jobbers, for the jobbers.” [11]

The fire of discontent kept spreading. Business leaders from Arnold’s base in South Washington convened a general meeting of Washingtonians to discuss a new system of government. Calling the D.C. commission “one of the most arbitrary in existence” and “dangerous to the interests of the city,” they proposed a new 14-man board with equal representation for each part of the city. Other activists demanded a return to suffrage. Within weeks, every neighborhood in Washington formed citizens’ associations and elected delegates to a Committee of 100, which could lobby Congress on behalf of the city.

In these discussions, the plight of Arnold and the police department faded from view. D.C. residents had a list of even more pressing complaints. Georgetown residents felt marginalized and wanted gas prices slashed. In Northeast, the citizens’ association demanded reforms to their decaying streetcars. Around modern day Logan Circle, water and lighting issues took center stage, with one furious resident noting that the only benefit of the neighborhood was that its lack of streetlights hid how dirty he was for lack of bathing water. The police scandal may have lit the fuse, but as the New York World put it, “nothing will satisfy the people here but a sweeping change.”[12]

Ultimately, though, a revolution did not arrive. Though furious at the commission, most white leaders did not want any power returned Black voters. They tabled resolutions calling for a return to democracy. Congress wanted nothing to do with reform either. Legislators worried that backing an investigation or reorganization of D.C. government would make them seem entangled in the police scandal and perhaps imply that they were a plump target for blackmail. But the campaign for government reform was hardly futile. The neighborhood committees got many of their grievances addressed. After these successes, they stayed organized and became staples of life in Washington, advocating for local communities before the Commission and Congress in the nine decades before democracy finally returned to the District. [13]

As the cause it launched faded, the police scandal itself slipped into obscurity. Maj. Walker returned to insurance, channeling his law enforcement passion into the Prohibition crusade. When Lt. Arnold’s Republican allies won the White House, and with it Washington, in 1888, he received the job of Inspector of Streets as compensation for his dismissal.[14] The pair and everyone else involved in the affair had an interest in letting the story pass unremembered by history, and it was quickly forgotten. Nonetheless, the police scandal of 1886 holds a sensational and impactful place in the long struggle for self-government in the District of Columbia.

Footnotes

- ^ “A New Chief of Police,” Washington Post, June 28, 1886, 1. “Major Dye’s Successor,” Washington Post, June 29, 1886, 2. “Maj. Walker's Well Deserved Rebuke,” Washington Post, July 5, 1886, 2. “New Detectives Named.: Maj. Walker Begins His Reorganization Of The Force,” Washington Post, July 16, 1886, 1. “Changing the Precincts,” Washington Post, July 22, 1886, 4. “An Increased Police Force.: Maj. Walker Submits Larger Estimates For Next Year,” Washington Post, September 5, 1886, 2.

- ^ Quote from Wilhelmus Bogart Bryan, A History Of The National Capital From Its Foundation Through The Period Of The Adoption Of The Organic Act, (New York : The Macmillan Company, 1914), 634. Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove, Chocolate City: A History Of Race And Democracy In The Nation's Capital, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 156-184.

- ^ “Emphatic Denials,” Washington Post, November 9, 1886, 4. “The Police Scandal,” Evening Star, November 9, 1886, 4. “Lieut. Arnold's Trial.: The President's Autograph Letter To Commissioner Webb,” Washington Post, November 13, 1886, 1.

- ^ For accounts of the trial’s first day, see “Lieut. Arnold’s Trial,” Evening Star, November 13, 1886, 1; “Lieut. Arnold On Trial.: An Unexpected Sensation At The Close Of The Day,” Washington Post, November 14, 1886, 1; and “Lieut. Arnold’s Case,” Washington Critic, November 13, 1886, 1.

- ^ “Lieut. Arnold On Trial,” Washington Post

- ^ For accounts of the trial’s second day, see “The Police Scandal: Arnold Tells His Story,” Evening Star, November 15, 1886, 1; “Lt. Arnold on the Stand,” Washington Post, November 16, 1886, 1; and “Hearing the Defense,” Washington Critic, November 15, 1886, 1.

- ^ “Gossip about the Trial,” Washington Post, November 15, 1886, 1. “Our Police Scandal,” Washington Post, November 18, 1886, 2. “The Police Scandal: What Members of Congress Say,” Evening Star, November 17, 1886, 1. “A Verdict Agreed Upon: It Is Said That Lieut. Arnold Will Be Acquited,” Washington Post, November 24, 1886, 1. “The Metropolitan Police Scandal,” Washington Bee, November 20, 1886, 1.

- ^ “The Police Scandal: The Arnold Case Still Pending,” Evening Star, November 17, 1886, 3.

- ^ Commissioners’ verdict as reprinted in “A Clean Sweep Made.: The Commissioners' Action In The Police Scandal,” Washington Post, November 25, 1886, 1.

- ^ Reactions described in “Clean Sweep,” Washington Post. Quotes from the Tribune as reprinted in “Who Shall be Chief,” Washington Critic, November 26, 1886, 1. “The Police Report,” Washington Critic, November 26, 1886, 2.

- ^ Quote from “Their Friends At Work: Admirers Of Lieuts. Arnold And Kelly Act With Vigor,” Washington Post, November 28, 1886, 2. “For Arnold and Kelly,” Evening Star, November 29, 1886, 4.

- ^ “The Local Government.: A Scheme To Reorganize It Under Consideration,” Washington Post, November 27, 1886, 1. “Who Shall be Chief,” Washington Critic. “The District Interests: A Meeting Held To Promote Them Before Congress,” Washington Post, December 9, 1886, 1. “Citizens' Association, No. 6,” Washington Post, February 20, 1887, 2. “Northeast Washington.: The Citizens; Improvement Association Discusses Local Affairs,” Washington Post, February 25, 1886, 4. “In A Neglected Condition.: The Citizens Of North Washington Appeal,” Washington Post, March 2, 1886, 3. “A Change Of Divisions.: Reorganizing The City Into New Association Districts,” Washington Post, March 29, 1887, 1.

- ^ “Who Shall Be Chief,” Washington Critic. “The District Interests,” Washington Post. “No Investigation Probable,” Washington Post, November 27, 1886, 2.

- ^ “An Anti-saloon League: Planning A Vigorous Fight Against The Granting Of Licenses,” Washington Post, October 2, 1888, 6. “Inspector Of Streets: Lieutenant Arnold Will Watch The Cleaning Of Thoroughfares,” Washington Post, August 16, 1889, 8.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)