Sit-ins Come to Arlington

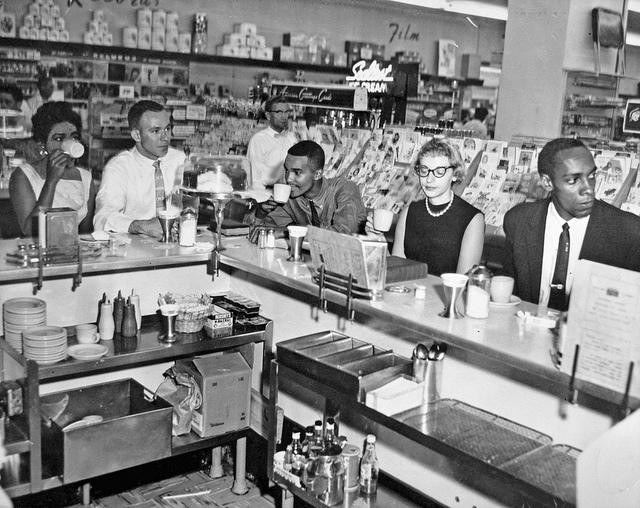

Shortly after 1 p.m. on June 9, 1960 a biracial contingent of college students entered the People’s Drug Store at Lee Highway and Old Dominion Dr. in Arlington and requested service at the store’s lunch counter. Less than a mile away, a similar group sat down at the counter at the Cherrydale Drug Fair.

Both lunch counters promptly closed.

Still, the students did not move. In fact, they remained seated for hours, calmly reading books and Bibles until well after dark, in protest of the stores’ refusal to serve African American patrons at their lunch counters.

The next day, the scene repeated itself and expanded to include two other establishments: another Drug Fair location at 5401 Lee Highway and the nearby Howard Johnson’s Restaurant.

For the most part, the Arlington sit-ins were calm and peaceful. Some white patrons even offered encouragement to the demonstrators. In fact, organizers would later point to the community’s reaction as proof that Arlington was ready for integration.

The major exception was at the Drug Fair in Cherrydale, where American Nazi Party leader George Lincoln Rockwell staged a counter-demonstration. Over the course of the two days, a crowd attempted to incite the students with taunts and abuse. At least one demonstrator had lit cigarettes placed in his pants.

As Dion Diamond told The Washington Post, “I’ve heard that term, n---, so much in the last few days – more than I’ve ever heard it before. But I kept thinking that if I struck back, I’d be defeating my purpose.”

When asked about the goals of the demonstration, Diamond continued, “I have friends in Arlington and frequently come to see them. I was told I couldn’t eat in a decent restaurant because of my race. I thought that if I could buy other things in a drug store or restaurant, I should get served. Some other students I know felt the same way, so we just decided to ask for service.”[1]

In fact, the sit-in effort was much more organized and coordinated than Diamond let on. The students represented the Non-violent Action Group (NAG) and were led by Howard University divinity student Laurence Henry. In all, about two dozen demonstrators participated in the Arlington sit-ins and just over half of them were Howard students. Others – including a number of whites – came from other universities.

The NAG had previously led several Civil Rights demonstrations in Washington, including picketing at the White House and U.S. Capitol.[2] The move to Arlington extended the group’s Civil Rights efforts and highlighted the hypocrisy of the segregation policies that existed there. Both the Drug Fair and the People’s chains already served black customers in the District and other states. However, the chains had elected to observe Virginia’s custom of segregation at their Arlington stores.[3]

According to Arlington County Board Chairman Herbert L. Brown, Jr., despite Virginia’s Jim Crow tradition, “Anybody may go into any commercial establishment and request service in an orderly manner. But it is private property and the owner has a right to make his own decision about whom he will serve.”[4]

Under Virginia’s trespassing laws, arrests could only be made if a business’s management preferred to press charges and most in Arlington didn’t – probably for fear of drawing increased attention in the press.[5] The lone exception was Howard Johnson’s, where Henry and Diamond were arrested on June 10.

For the students, occupying seats at the lunch counters was just the first step in a process toward change. What they were ultimately after was a dialogue with business owners and community leaders, as the NAG explained in a formal statement to the press: “Our aim is to effect community discussion and action on immediate and orderly racial integration of eating facilities…mediation now seems desirable for two reasons: for the improvement of Arlington community relations and for the economic well being of the community.”[6]

Toward that end, the group put a temporary halt to the sit-ins late on the evening of June 10 to give Arlington leaders the opportunity to start mediation with store managers.[7] But, in doing so, they promised more sit-ins if no meaningful progress was made in the following days. The students followed with letters to County Board members urging them to facilitate a meeting between the demonstrators, business owners, and community leaders.

Henry sensed that the Arlington community was ready for change. “We noticed the public is quite willing to accept integrated eating facilities in the areas in which the demonstrators have appeared in Arlington County.” The problem, he explained, was that “no one wants to be first.”[8]

With no measurable progress made in a week, NAG re-started the sit-ins on June 18, occupying lunch counters at the Woolworth’s and Landburgh’s department stores in Shirlington. Like Drug Fair and People’s those chains were already serving black patrons in D.C. and Maryland.

With the threat of more demonstrations to follow, business owners finally capitulated. On the morning of June 22, F.W. Woolworth’s announced that it was desegregating its lunch counter in Shirlington, effective immediately. Later that same day, Drug Fair, People’s, Landburgh’s, and Kahn’s made similar announcements.

County Board Chairman Herbert Brown applauded the decision as “consistent, reasonable and fair,” and predicted that “most people will quietly accept it as such.”[9]

The student demonstrators were, of course, pleased with the decision as well but kept looking ahead. As Laurence Henry said, “We are extremely happy. We hope this action will inspire other chain and department stores to adopt a similar policy.”[10]

It did. Within days, nearly all chain department stores and drug stores in Arlington, Alexandria, and Fairfax had integrated their lunch counters – most of which NAG had never visited.

For more photos of the Arlington sit-ins, visit the Washington Area Spark Flickr collection.

Footnotes

- ^ McBee, Susanna. “Negro Relates Objectives of Sitdown”. The Washington Post, 12 June 1960: B14.

- ^ Triggs, Jan Leighton and John Paul Dietrich. “Freedom Movement in Washington DC: 1960-61. Based on the Actions of the Nonviolent Action Group (NAG) 1961, Revised 2011.

- ^ McBee, Susanna, “Negro Relates Objectives of Sitdown,” The Washington Post, 12 Jun 1960: B14.

- ^ “Two Negroes in Restaurant Sitdown Held for Trespassing,” The Washington Post, 11 Jun 1960: D1.

- ^ McBee, Susanna and Elsie Carper, “Sitdown Comes to N. Virginia,” The Washington Post, 10 Jun 1960: D6.

- ^ “Two Negroes in Restaurant Sitdown Held for Trespassing,” The Washington Post, 11 Jun 1960: D1.

- ^ “Two Negroes in Restaurant Sitdown Held for Trespassing,” The Washington Post, 11 Jun 1960: D1.

- ^ Anderson, John, “Arlington Accepts Lunch Integration Say Sitdowners,” The Washington Post, 19 Jun 1960: B2.

- ^ McBee, Susanna, “2 Drug Outlets, 3 Major Stores Desegregate Arlington Counters,” The Washington Post, 23 Jun 23, 1960: A1.

- ^ McBee, Susanna, “2 Drug Outlets, 3 Major Stores Desegregate Arlington Counters,” The Washington Post, 23 Jun 23, 1960: A1.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)