Eleanor Roosevelt and the Bonus Marchers

In 1932, as the nation lingered in the desperate depths of the Great Depression, thousands of World War I veterans and their families marched on Washington to demand immediate lump-sum payment of their military pensions. To the consternation of President Herbert Hoover, who was about to embark upon a difficult reelection campaign, the ragtag army camped in tents and shacks along the Anacostia River, and began trying to pressure the White House and Congress by marching up and down Pennsylvania Avenue. Unfortunately, the bill to pay them their benefits passed the House but was overwhelmingly defeated in the Senate in June.

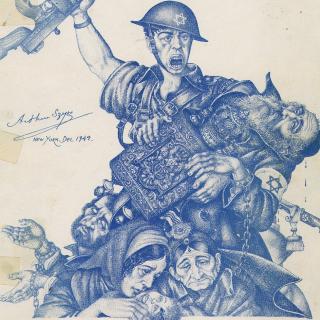

The marchers stubbornly stayed, and rebuffed the Hoover administration's offer of train fare out of town. In response, Hoover decided to evict them by force. On July 28, in one of the most disturbing moments in the history of Washington, U.S. horse cavalry wearing gas masks and steel helmets, and backed by five tanks, descended upon the bonus marchers, scattering them and their wives and children and burning their campsites.

What some called the Battle of Washington made a powerful impression upon soon-to-be First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, whose husband would unseat Hoover in the fall of 1932. According to biographer Blanche Wiesen Cook, Eleanor wrote the incident "shows what fear can make people do," and she was determined to do whatever she could to prevent such a thing from ever happening again.

It wouldn't be long before she got her opportunity.

In May 1933, the marchers returned to demand their bonus and protest President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Economy Act, which actually had reduced what benefits they already were receiving. But this time, the veterans weren't met by bayonets. Instead, Roosevelt sent adviser Louis Howe to meet with their leaders, and provided a clean campsite for them at Fort Hunt in Virginia, including sanitation and three meals each day. Roosevelt, who didn't want to give veterans preference over other needy Americans, balked at paying the lump-sum bonus too. But according to historian Alfred B. Rollins, Jr., the President had Howe offer them a concession — his administration would offer spots to marchers who wanted to enlist in the Civilian Conservation Corps, a public works jobs program, and the fort would be converted into a training camp for them. To ease the bitterness and build support for the deal, Howe and Roosevelt decided to resort to their most persuasive asset: Eleanor Roosevelt.

On the afternoon of May 16, 1933, according to Cook's and Rollins' accounts, Howe asked Eleanor to take him for a drive, without explaining the purpose. As they neared Fort Hunt, he explained that the President needed her to visit with the bonus marchers, and that it would be best if she did it alone — an idea to which the Secret Service would have objected strenuously, if they had known. But the First Lady, who liked mingling with the public sans handlers, agreed.

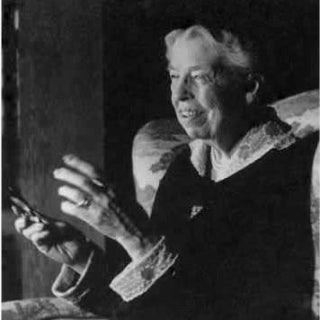

While Howe dozed in the car, Eleanor got out and walked right into the camp, and headed for a line of men were waiting for food. "They looked at me curiously, and one of them asked my name and what I wanted," she later recalled. "When I said I just wanted to see how they were getting on, they asked me to join them." Pretty soon, they were reminiscing about the war, and she joined them in singing old Army songs, such as "There's a Long, Long Trail a-Winding" and "Pack Up Your Troubles in Your Old Kit Bag."

Eleanor spent an hour on an impromptu tour of the veterans' camp, wading through ankle-deep mud to visit their living quarters and the camp's hospital. In the camp's convention tent, marchers gathered to hear her impromptu speech. She apologized for not being able to tell them anything about the bonus, but explained that she understood their frustration. During the war, she told them, she had volunteered to drive a truck into the railroad yards at night and served sandwiches and coffee to soldiers who were waiting to ship out. She also told them of seeing wounded veterans return on crutches, and how she had been moved by the sight.

"I never want to see another war," the First Lady told the marchers, who interrupted her speech repeatedly with cheers, according to Cook. "I would like to see fair consideration for everyone, and I shall always be grateful to those who served their country. I hope we will never have to ask such service again." The veterans then accompanied her back to the car, and waved as she drove off.

It was the First Lady's first effort acting as an emissary for the White House, according to Cook. And though Eleanor would have preferred to pay the soldiers their bonus, she could at least take some satisfaction in how the "grand-looking boys" had been treated humanely by her husband's administration.

By June, about 2,600 veterans had accepted CCC jobs — though some rejected the $1 daily wage as too meager. In 1936, Congress finally passed a bill authorizing early payment of the veterans' benefits, overriding the President's veto. Three million former soldiers received nearly $2 billion, which worked out to $580 per man. During World War II, the President changed his position on veterans benefits, and in 1944 signed the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, which became better known as the G.I. Bill. The educational benefits and assistance to homebuyers and small-business entrepreneurs in the legislation helped to create a well-educated, prosperous cadre of veterans whose consumption helped make the 1950s a prosperous era.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)