Thomas Edison's D.C. Invention

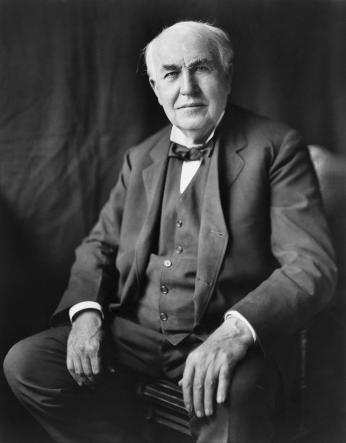

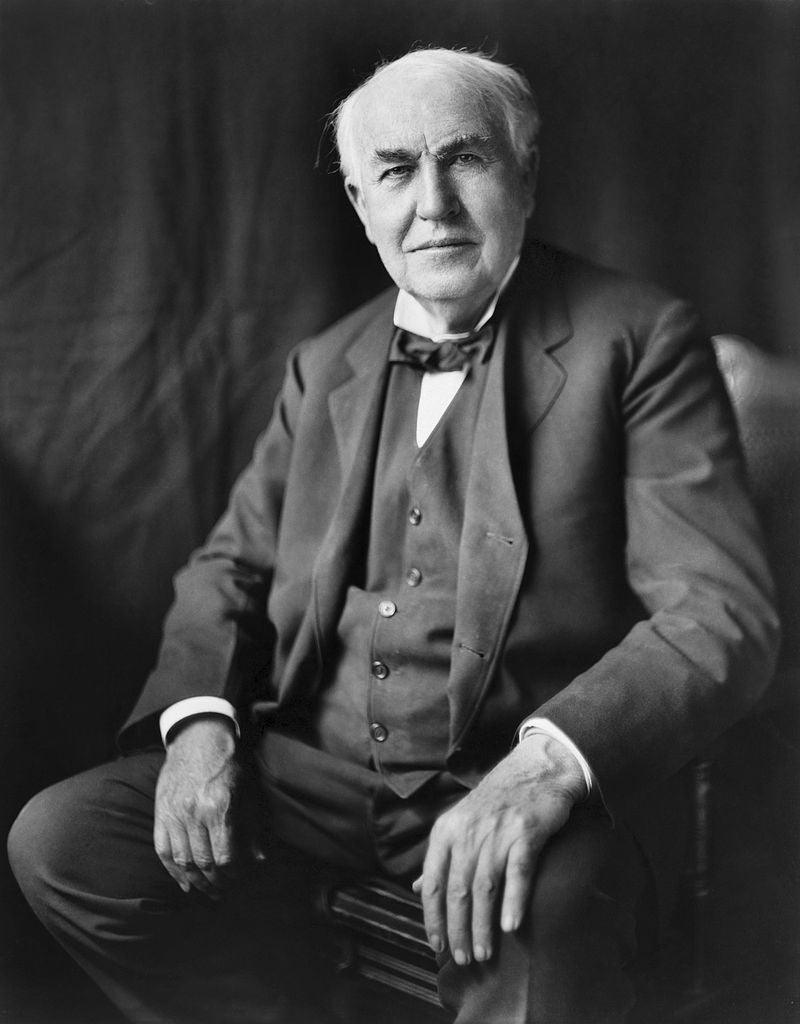

The year was 1915. World War I was raging in Europe and Americans were uneasy at the prospect that their country would soon be brought into the conflict. As a man with a history of creative ideas, it’s no surprise Thomas Edison had some thoughts on the situation and he was not shy about sharing them.

On May 30, 1915 the New York Times ran a two-page spread entitled, “Edison’s Plan for Preparedness,” in which the inventor spoke at length about how the United States could learn from the mistakes made by the combatants in Europe and build a highly-efficient war machine.

Citing his faith in American ingenuity and industrial prowess, Edison’s ideas ran from manufacturing improvements to developments in transportation and weapons production. But perhaps his most far-reaching (and locally significant!) proposal was this:

“The Government should maintain a great research laboratory, jointly under military and naval and civilian control. In this could be developed the continually increasing possibilities of great guns, the minutiae of new explosives, all the technique of military and naval progression, without any vast expense. When the time came, if it ever did, we could take advantage of the knowledge gained through this research work and quickly manufacture in large quantities the very latest and most efficient instruments of warfare.”[1]

Picking up the newspaper in Washington, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels was intrigued. The Navy was already receiving many of proposals from civilians and companies suggesting new inventions that would aid in national defense. But, with no single department tapped to consider them, these ideas largely fell by the wayside.

Seizing on Edison’s suggestion of a civilian-military research lab, Daniels reached out to the inventor to gauge his interest in chairing an advisory board for the Navy – which would later be called the Naval Consulting Board on Inventions – “to which all ideas and suggestions, either from the service or from civilian inventors, can be referred for determination as to whether they contain practical suggestions for us to take up and perfect.”[2]

The board would consist of two dozen scientific leaders from around the country. But, in the eyes of the Secretary, Edison’s participation was particularly crucial: “I feel that our chances of getting the public interested and back of this project will be enormously increased if we can have, at the start, some man whose inventive genius is recognized by the whole world to assist us in consultation from time to time on matters of sufficient importance to bring his attention. You are recognized by all of us as the one man above all others who can turn dreams into realities.”[3]

Edison was interested (and perhaps also flattered by the Secretary’s praise) and he accepted the appointment on July 13. However, in doing so, he once again urged the government to think bigger: “In addition to the Advisory Board of Engineers I would also suggest a department of experimentation, where ideas might be tried out. The cost would be nominal. Only a few acres of land would be required with proper buildings and a corps of efficient men.”[3]

With the war raging on, the idea for a lab gathered steam. In October, the board unanimously approved Edison’s proposal, which called for a lab complex with “complete equipment, to enable working models to be made and tested to destruction.” Facilities would include a woodworking shop, a brass foundry, a cast iron and steel foundry, a chemical lab, a motion picture developing and printing department and an explosives lab amongst other specialties. It was pretty much an inventor’s heaven.

A naval officer would be put in charge and lead a team of lower ranking Navy experts and civilian scientists. The lab was to be located “on tidewater of sufficient depth to permit a dreadnought [battleship] to come to dock and that it be near but not in a large city.” Edison personally drew the plans for the campus, which the press touted as “the greatest research laboratory in the world, where work that now takes months to accomplish can be finished in as many days.”[4] Congress approved an initial allocation of $1.5 million for the project in 1916.

But exactly where would this world-class lab be built?

As one might imagine, it was an attractive project and cities lined up to make their pitches. The mayor of Baltimore put together a delegation to meet with Navy officials and make the case for that city; Philadelphia expressed an interest, as did New York and other jurisdictions.

Most on the board leaned toward a site on the Severn River near the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, while Edison favored New York. Meanwhile, many senior government officers preferred putting the lab in Washington so that it would be close to the Navy Department. Skeptics of the D.C. location claimed that the Potomac River was not wide or deep enough to accommodate the ships the lab would require for its tests.

The lack of consensus delayed the project. So, too, ironically, did America’s entry into the war. As the Washington Post reported in June 1917, “The explanation to postpone construction of this plant is that practically without exception the inventors and scientists that are working on naval problems have excellently equipped laboratories in which to carry on their work. Therefore, it is felt that equipping one at great cost to the government at this time would be unwise, not only on account of the money involved, but also on account of the sidetracking of valuable skilled labor and much needed officers.”[5]

So, Edison’s dream of creating an invention laboratory to help the war cause would have to wait until after the war was over? Yes, pretty much.

Fortunately, however, the project did not die altogether as, even in peace time, officials still recognized its potential. In 1920, the government finally decided to build the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington “on the site of the old powder magazine at Bellevue, on the District side of the Potomac River.”[6]

The United States Naval Research Laboratory began operations on July 2, 1923 and remains one of the nation’s premier research and development installations today. Since 1953, visitors to the lab have been greeted by a large bust of Edison at the NRL’s front gate, which was sculpted by Evelyn Beatrice Longman (who also did work on the Lincoln Memorial) and presented to the Navy by the Thomas Alva Edison Foundation, Inc.[7]

Footnotes

- ^ Marshall, Edward, “Edison’s Plan for Preparedness: The Inventor Tells How We Could Be Made Invincible in War Without Overburdening Ourselves With Taxation,” New York Times, 30 May 1915: SM6.

- ^ “Thomas Edison’s Role In Birth Of Navy’s Department Of Invention And Development,”CHIPS, The Department of the Navy’s Information Technology Magazine, 11 Jul 2014.

- a, b “Edison Will Head Navy Test Board,” New York Times, 15 Jul 1915: 1.

- ^ “Our Navy Torpedo Called the Best,” New York Times, 10 Feb 1916: 3.

- ^ “Army and Navy Gossip,” The Washington Post, 17 Jun 1917: A3.

- ^ “News of the Army and Navy,” The Washington Post, 3 Oct 1920: 24.

- ^ “Thomas Edison’s Vision,” Navy Research Laboratory website. Accessed 27 Jan 2015.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)