Red Summer Race Riot in Washington, 1919

By all accounts, Saturday, July 19, 1919 was a hot, muggy night in Washington, D.C. The stifling heat probably didn’t help the disposition of patrons in the city’s saloons which, in this era of early-Prohibition, could only offer the tamest of liquid refreshments.[1] (Though, undoubtedly many barflies acquired stiffer drinks at one of the city’s many speakeasies.) It probably didn’t help matters, either, that many of the soldiers and sailors who had recently returned home from the battlefields of World War I were struggling to find work.

The day’s Washington Times reported that Mrs. Elsie Stephnick, a white woman who worked in the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, had been assaulted by “2 negro thugs” on her way home from work the previous evening. The paper noted, “This is the sixth attack made on women in Washington since June 25 and while the police are working day and night in an effort to arrest the negro assailant of the women, only two suspects are in custody.”[2]

In the Times’ estimation, the nation’s capital was in the midst of a crime wave of the worst kind. Indeed, in the Jim Crow era, nothing incited the white community like the idea of violence perpetrated by black men toward white women—real or, many times, fabricated.[3]

Rumors began to circulate that police had picked up Charles Ralls, a black man from the city’s primarily African-American Southwest quadrant, but had released him after questioning. Deciding to take matters into their own hands, a throng of sailors, soldiers, marines and veterans gathered near the Knights of Columbus hut at 7th and Pennsylvania, NW around 10 pm.

The mob – which included many men in uniform – swelled to over 200 during the march to Southwest. En route, they attacked African Americans they encountered on the street, including George Montgomery, a 55-year old who was severely beaten while grocery shopping. Upon spotting Charles Ralls and his wife out walking, the mob gave chase. The Ralls barricaded themselves into their home as neighbors came to their defense. Gunfire pierced the summer air.

When police arrived, two white ringleaders and eight black men were arrested. However, that did little to cool off the simmering hostilities. The next evening, a similar mob formed and targeted African Americans along Pennsylvania Avenue in NW, beating pedestrians and pulling black riders off of streetcars. The Washington Herald reported that “Many civilians, defiant of the police, were openly advocating lynching.”[4]

District Commissioner Louis Brownlow spoke out against the violence, “The actions of the men who attacked innocent negroes cannot be too strongly condemned, and it is the duty of every citizen to express his support of law and order by refraining from any inciting conversation or the repetition of inciting rumors and tales.”[5]

However, the attacks continued and—with police unable to quell the violence—many black Washingtonians took matters into their own hands. As the Post reported: “In the negro district along U Street from Seventh to Fourteenth streets, the negroes began early in the evening to take vengeance for the assaults on their race.”[6]

The Afro American newspaper applauded both the black community’s initial restraint and its change heart: “To the credit of the colored citizenry of the Capital, it can be said that in the first stages of the riot, no single colored man took the initiative of creating disturbances. Every time whites were the aggressors until human nature could stand it no longer, and in pure defense groups of men in fifties and hundreds went out to show the attackers that the colored population was not altogether defenceless. [sic]”[7]

Monday, July 21 saw the worst violence. In addition to the mob clashes on the streets, assailants assaulted people in streetcars and shot from automobiles. At the Navy Hospital on 23rd St., NW, four African Americans fired at convalescing sailors before driving away. Along the H Street corridor in NE, three whites were seen shooting from a vehicle.[8] Clashes seemed to be happening on nearly every corner. As one news report put it, “At times the mob outrages on both sides of the color-line were so staged as to suggest a fine Machiavellian hand back of them all and pulling the wires.”[9]

Though Brownlow and the other commissioners had been reluctant to appeal to the President for martial law, Wilson mobilized about 2,000 troops to restore order late on July 22. Their presence, along with a fortuitous summer storm, finally succeeded in stamping out the riots. According to the Post, “Raindrops were as effective as bullets in dispersing the downtown crowds and sending the individuals scurrying for shelter in doorways and under awnings. Many of them tired of dodging both rain and policemen, went home.”[10]

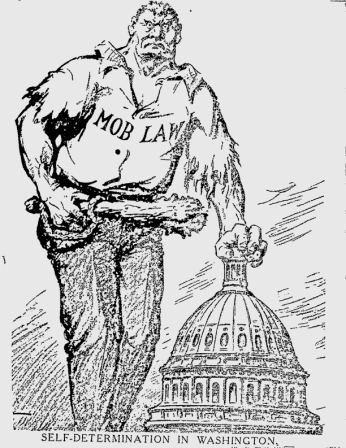

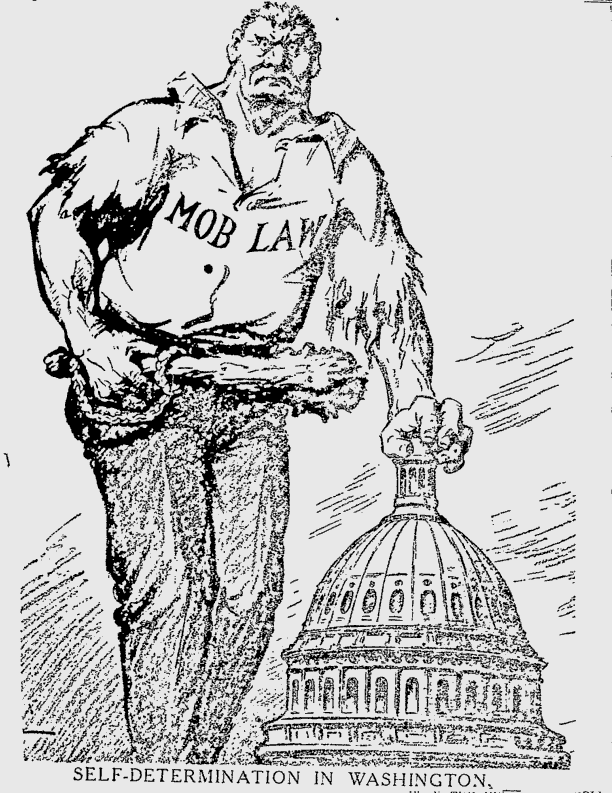

When it was all over, it was clear that the hostilities were unlike anything Washington had experienced before. Multiple people, both black and white, were killed and scores more had been hospitalized. As the Times put it, “There is no precedent in Washington’s history for such a race riot as this, and the law-abiding element of the town was amazed at the sight of law and order toppled over in the flame of the sinister passions engendered.”[11]

Congress and local Washingtonians alike tried to make sense of it all. Some pointed to the poor pay of the city’s police officers. Others suggested that enforcement of Prohibition (which had begun in D.C. in 1917, three years before the rest of the country went dry) had stretched the department too thin. One Congressman even went so far as to say that homemade whiskey was the culprit: “Drinking too much green whisky is responsible for this unprecedented wave of crime over the Nation’s Capital.… It is making them stark mad, that’s what’s the matter.”[12]

An editorial in The Evening Star was probably closer to the mark: “The cause is undeniably an intense race animosity that has been developing for some time.”[13] Indeed, as journalist Peter Perl wrote in 1999, post World War I Washington was “a racial tinderbox.” Housing and jobs were in short supply and there were deep resentments on both sides.

Many whites resented the modest gains that Washington’s black community – then about 25% of the city’s population – had made in the decades before the war, during which

Federal government offices were (relatively) integrated and offered good jobs to African Americans. Meanwhile black Washingtonians – particularly returning soldiers who President Wilson had sent to Europe “to make the world safe for Democracy” – resented the growing discriminatory Jim Crow policies at home. (Indeed, Wilson, had effectively re-segregrated the Federal government during his first term.)

In 1919, these tensions finally came to the surface. Sadly, the scene would be repeated in cities across the country in what Civil Rights activist and author James Weldon Johnson termed "Red Summer."

Footnotes

- ^ While Prohibition went into effect across the country in 1920, it was the law in Washington three years earlier. Dry proponents in Congress sought to make the nation’s capital a model dry city.

- ^ “Screams Save Girl From 2 Negro Thugs.” The Washington Times. (Washington [D.C.]) 1902-1939, July 19, 1919, FINAL EDITION, SECTION TWO, Image 11, July 19, 1919.

- ^ The Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia has a detailed article about the stereotypes of black men, which proliferated during the 19th and early 20th centuries. These stereotypes routinely characterized African American males as brutes with an instatiable desire for white women. “JCM: The Brute Caricature.” Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia. Accessed April 13, 2017.

- ^ “Score of Negroes Hurt as Race Riot Spreads; Police Make 6 Arrests.” The Washington Herald. (Washington, D.C.) 1906-1939, July 21, 1919, Image 1, July 21, 1919.

- ^ “Brownlow Urges Citizens Not to Come Downtown Tonight.” The Washington Times. (Washington [D.C.]) 1902-1939, July 21, 1919, FINAL EDITION, Image 1, July 21, 1919, Final edition.

- ^ “DETECTIVE SERGEANT WILSON VICTIM; OTHER OFFICERS HURT; NEGRO RUNS AMUCK, WOUNDING MANY IN FLIGHT: Fighting Spreads to Many Sections After Troops Form a Cordon Around Center of City. Martial Law Virtually in Force Downtown From White House to Mall and Capitol, Thence to H, K and L Streets Northwest. One Policeman Wounded -- Negroes Fired on Whites From Speeding Autos.” The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. July 22, 1919.

- ^ “Washington Riots.” The Afro American, July 25, 1919. p 4.

- ^ “Colored Men Shoot at Patients and Sentry; Provost Aids Police.” Evening Star. (Washington, D.C.) 1854-1972, July 21, 1919, Image 1, July 21, 1919.

- ^ “Police Stations Refuge Centers For Terrified Families Who Fled Bullets.” The Washington Times. (Washington [D.C.]) 1902-1939, July 22, 1919, FINAL EDITION, Image 2, July 22, 1919.

- ^ “GEN. HAAN IN COMMAND AFTER WILSON CONFERS WITH BAKER ON RIOTS: Score More Shootings as Fighting Is Resumed in Various Parts of City’s Outlying Districts. Home Defense Officer Isaac Halbfinger Slain by Negro He Attempts to Arrest -- G. Belmont, Another Home Defense Officer, Fatally Injured Also by Negro’s Shot. Numerous Other Clashes Result in Serious Injuries to Negroes and White Men -- Many Treated at Hospitals -- Scores of Both Races Arrested by Police and Military. ONE DEAD AND ANOTHER WOUNDED; NEW VICTIMS OF NEGRO BULLETS.” The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. July 23, 1919.

- ^ “Police Stations Refuge Centers For Terrified Families Who Fled Bullets.” The Washington Times. (Washington [D.C.]) 1902-1939, July 22, 1919, FINAL EDITION, Image 2, July 22, 1919.

- ^ “Riots Taken Up in Congress; Kahn Blames New ‘Dry’ Law; Inquiry Is to Be Asked Today: Some Members Criticize Maj. Pullman and Police Generally -- Senate and House District Committees Ready to Increase Pay and Obtain More Men for the Force -- Opinions Expressed.” The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. July 22, 1919.

- ^ “A Climax of Mob Crime.” Evening Star. (Washington, D.C.) 1854-1972, July 22, 1919, Image 6, July 22, 1919.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)