Nixon's Weirdest Day

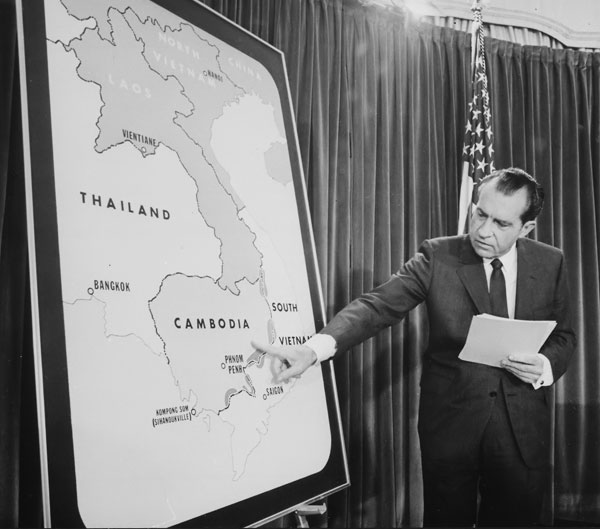

On April 20, 1970 President Nixon addressed the nation outlining his plan for the withdrawal of 150,000 troops from Vietnam, signaling that he was serious about his promise to get America out of the war. Ten days later however, the anti-war movement was stunned by his announcement of a major new escalation in the fighting — the U.S. invasion of Cambodia. Campuses across the country exploded in dissent, culminating in the killing of four students at Kent State University by National Guard troops on May 4.

In the tense days following Kent State, impromptu rallies erupted all over the Washington region, and a major demonstration was planned for May 9 on the National Mall. Law enforcement entities went on hair-trigger alert, mobilizing all available resources including the entire D.C. police force and 5,000 locally-stationed troops.[1]

“Henry Kissinger said Washington and the White House were besieged. There were district buses lined up around the White House for who knows what. The 82nd Airborne was in the basement of the Executive Office Building across the street.” [2]

It was in this combustible atmosphere that an idea germinated in Richard Nixon’s muddled mind in the wee hours of May 9, 1970. It would prove to be one of the most bizarre incidents of his presidency, and that’s saying a lot.

After a contentious press conference at 10 p.m. on Friday, May 8, Nixon stayed up until 2:15 a.m. making phone calls. He slept for a couple of hours, woke up, put on a classical music album (Rachmaninoff), and peered out the window at the gathering crowds on the mall. He then hatched a not-so-brilliant plan — he would take his valet, Cuban immigrant Manolo Sanchez, down to the Lincoln Memorial. Ostensibly, Nixon wanted to provide Manolo with the opportunity to see the monument lit up at night for the first time. While there, perhaps, he just might talk some sense into the young anti-war protesters. So he informed the “petrified” secret service, and the small party left the barricaded White House in darkness around 4:35 a.m.[3]

Upon arriving at the Lincoln Memorial, Nixon engaged a small (but steadily growing) group of protesters camped out for the rally scheduled to begin later that day. Nixon, as always socially awkward, tried to get the dialogue started with some small talk:

"To get the conversation going I asked how old they were, what they were studying, the usual questions." When several of the students said they attended Syracuse University, Nixon commented on how good the school's football team was. Far from being overawed, the students found Nixon's line of questioning downright bizarre.[4]

"I hope it was because he was tired but most of what he was saying was absurd," one of the Syracuse students told The Washington Post afterward. "Here we had come from a university that's completely uptight, on strike, and when we told him where we were from, he talked about the football team. And when someone said he was from California, he talked about surfing."[5]

Nixon's rambling dialogue covered various topics from travel and marriage to race relations and pollution, but eventually, the President got around to his primary purpose — explaining his recent actions on Vietnam as motivated by a desire for peace:

“I had tried to explain in the press conference that my goals in Vietnam were the same as theirs — to stop the killing, to end the war, to bring peace. Our goal was not to get into Cambodia by what we were doing, but to get out of Vietnam.

There seemed to be no — they did not respond. I hoped that their hatred of the war, which I could well understand, would not turn into a bitter hatred of our whole system, our country and everything that it stood for.

I said, I know you, that probably most of you think I’m an SOB. But I want you to know that I understand just how you feel.”[6]

As the dawn approached and rays of sunshine spread over the Mall, Nixon decided it was probably time to wrap up the rap session, and headed back to the Presidential limousine, to the great relief of his small (and increasingly apprehensive) Secret Service detail.

But Dick and Manolo’s excellent adventure wasn’t over just yet. The President ordered the detail over to the Capitol, where they walked through the nearly-deserted building with tour guide Nixon pointing out the sights in the House Chamber.

"He [Nixon] takes a seat in his old representative seat. And he asks Manolo to go up to the speaker’s platform and to deliver a short speech. Then they go off to breakfast. He said he hadn’t had hash ever since he had been president. They try a famous hash diner.

That was closed. So they went off to the Mayflower Hotel and had breakfast. And only after that did he go back to the White House, after this amazing evening, early morning."[7]

Nixon’s now infamous pre-dawn sojourn took place at a tumultuous time for his presidency, when the nation seemed to be fraying along social, political and racial lines. But his erratic behavior that morning would have even his closest allies wondering if he was going off the deep end. Nixon's Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman wrote in his diary hours after the Lincoln Memorial visit, "I am concerned about his condition," and noted that Nixon's behavior that morning constituted "the weirdest day so far."[8]

Footnotes

- ^ “5,000 Troops Alerted For Saturday's Rally,” by Carl Bernstein; The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); May 8, 1970; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post

- ^ Melvin Small, PBS NewsHour interview, “New Nixon Tapes Reveal Details of Meeting With Anti-War Activists,” November 25, 2011

- ^ “Dawn at Memorial: Nixon, Youth Talk: President Pays Visit to Protesters,” by Don Oberdorfer; The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); May 10, 1970; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post; Dictation of a memo by the President to Haldeman regarding the President’s visit with college students at the Lincoln Memorial; Textual Location: WHSF—SMOF—President's Personal File—Box 2—Memos-May 1970, Date: 05-13-1970; Audio: DB076_04.mp3; Nixon Presidential Library

- ^ “I Am Not a Kook: Richard Nixon's Bizarre Visit to the Lincoln Memorial,” by Tom McNichol, Nov. 14, 2011, The Atlantic

- ^ “Dawn at Memorial: Nixon, Youth Talk: President Pays Visit to Protesters,” by Don Oberdorfer; The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); May 10, 1970; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post

- ^ Dictation of a memo by the President to Haldeman regarding the President’s visit with college students at the Lincoln Memorial; Textual Location: WHSF—SMOF—President's Personal File—Box 2—Memos-May 1970; Date: 05-13-1970: Audio: DB079_01.mp3; Nixon Presidential Library

- ^ Melvin Small, PBS NewsHour interview, “New Nixon Tapes Reveal Details of Meeting With Anti-War Activists,” November 25, 2011

- ^ “I Am Not a Kook: Richard Nixon's Bizarre Visit to the Lincoln Memorial,” by Tom McNichol, Nov. 14, 2011, The Atlantic

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)