Mussolini’s Mysterious Stay at St. Elizabeths Hospital in DC

St. Elizabeths Hospital has had its fair share of infamous patients. Would-be Presidential assassins Richard Lawrence and John Hinckley, silent film actress Mary Fuller, and “The Shotgun Stalker” James Swann have all called the psychiatric hospital home. But the building has also had some lesser-known, but equally significant, guests – or at least parts of them. St. Elizabeths quite literally got a piece of Benito Mussolini’s mind when sections of his brain were sent there for research in 1945. That’s right: as literary great Ezra Pound spent time in the Chestnut Ward, a portion of his fascist idol was just next door. And while Pound left after twelve years, the brain remained, shrouded in obscurity, until its eventual disappearance more than twenty years later.

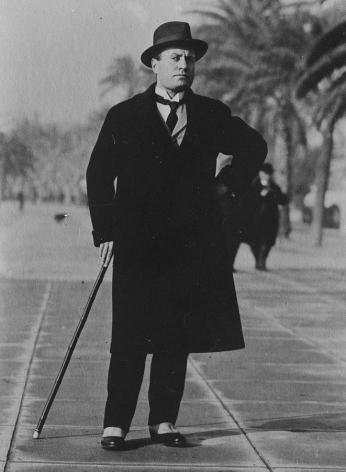

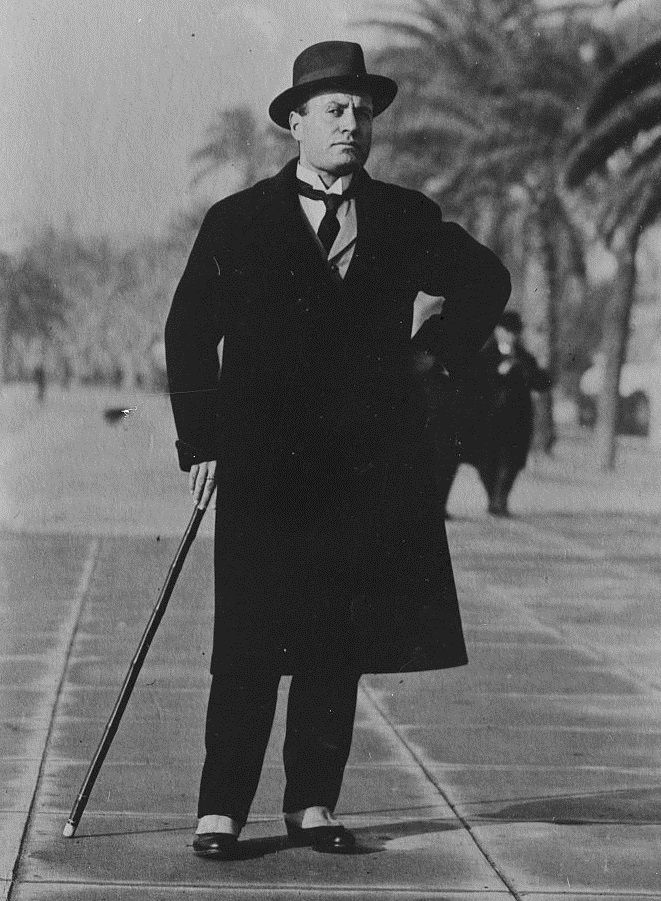

Let’s go back to April of 1945. It was the final year of World War II, and things weren’t going well for Il Duce. Allied forces were invading Italy, and as he attempted to flee, Mussolini was captured by Communist partisans near Lake Como. There, he was executed with his mistress, Clara Petacci, and taken to Piazzale Loreto in Milan. His body hung with other Fascists from a gas station, head down, and “for the first time, the common people could reach out and touch their untouchable leader.”[1] They did so brutally, throwing punches, kicking, and spitting. Weeks later, an autopsy conducted at the University of Milan revealed a misshapen head due to destruction of the cranium, and damage to the cerebellum, midbrain, and parts of the occipital lobes.[2] Mussolini’s brain was basically a piece of mush, and Americans wanted a slice of it.

Rumors had recently taken off telling of Mussolini’s struggle with general paresis, a disease which impairs mental function due to untreated syphilis.[3] Dr. Winfred Overholser, superintendent of St. Elizabeths and a scholar of psychiatry’s role in the war, itched to look into this diagnosis. Many believed Mussolini’s erratic behavior (his outlandish uniforms, his pet lion, his ideas of empire building) could be attributed to this brain damage, and Dr. Overholser wished to test the theory. Unaware of the state of the dictator’s brain, he requested specimens. Months later, Italy’s Institute of Legal Medicine divided the brain and sent test tubes across the Atlantic.[4] Their destination: Washington, D.C.

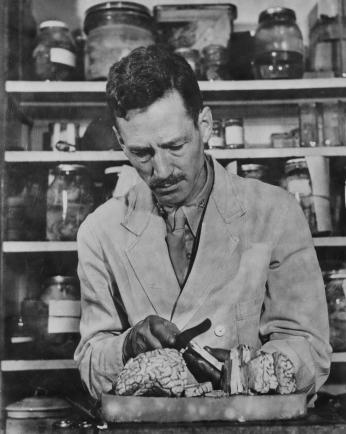

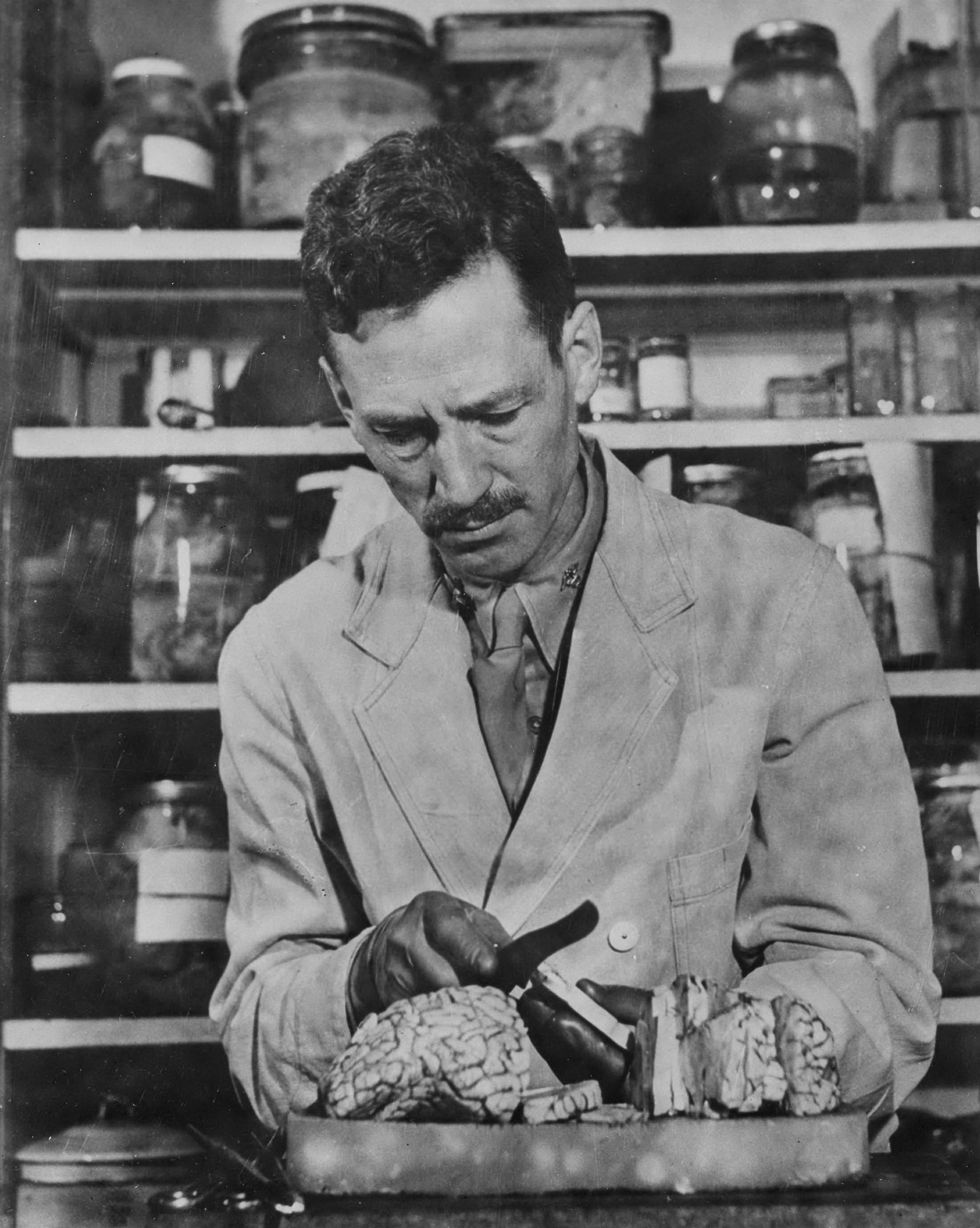

Despite the obvious damage done in Piazzale Loreto, Dr. Overholser and Dr. Webb Haymaker[5] at the Army Institute of Pathology (later the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology) began their study of Mussolini’s gray matter in the fall of 1945. By November, the investigation had fallen flat. The researchers determined that Mussolini’s brain was quite normal. They ascertained that the dictator was most likely not afflicted with paresis, and that no visible brain damage could have accounted for his mad quest for power. “As far as looks and structures are concerned,” wrote the editors of the Evening Star, “ his gray matter and white matter could just as well have been that of any reasonably healthy human being or could have belonged as much to a peace-loving non-Fascist as to him.”[6]

Of course, there was the possibility that the Milanese mob had destroyed any evidence of a mental disorder in Mussolini. But Dr. Overholser doubted it, considering Mussolini’s behavior before the rumor of paresis arose (because, you know, he had already founded fascism and created a dictatorship.)[7] In all likeliness, Mussolini was just an abnormal guy with a normal brain. The study proving fruitless, the doctors shut it down, and the brain matter was filed away and forgotten: half at St. Elizabeths, and half at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology.

It resurfaced again ten years later, in July of 1955, when Evening Star reporter John McKelway heard gossip about Mussolini’s brain quartered in the archives of St. Elizabeths. The study of the brain had turned largely into legend by this time, and McKelway didn’t expect much as he headed over to the hospital. But he was lucky. After poking around a bit, he got a hold of Dr. Overholser himself, who went into his safe and pulled out a small glass vial. “Floating in the bottle in preservative was something resembling a chicken’s liver,” McKelway wrote. “The label on the bottle sent one’s thoughts back to the dictator’s ignominious end. The label read: ‘Mussolini brain.’”[7]

McKelway was the last to see this sliver of Il Duce’s brain. Although the article he published broke the news of its presence in the city to many Washingtonians, its hype quickly faded, especially as people learned of the futility of its study. Before long, the brain had floated once again into obscurity. It remained secured in Dr. Overholser’s safe until his death in 1964, and even then, it remained forgotten. It wasn’t until 1966 that the brain entered the public’s eye once more.

The brain matter hadn’t been the only part of Mussolini’s body traveling around the world since his death. His corpse itself had had quite the journey. After being kidnapped by Fascist adherents and moved around Italy for sixteen weeks, it was hidden in a Capuchin monastery for eleven years, and even Mussolini’s widow and children were unaware of its location. It wasn’t until 1957 that Republican leaders returned Mussolini’s body to his family, where it was buried in a crypt in his hometown of Predappio.[8] But Rachele Mussolini claimed she would not be satisfied until all of her late husband rested in the same place. For eight years, she wrote to James D. Zellerbach, United States Ambassador to Italy, demanding the bits of his brain back.[9] In 1966, her plea was finally heard.

Officials had no problem finding the half of the brain slivers stored away at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. But when it came time to search for the sample once kept in Dr. Overholser’s safe, the St. Elizabeths staff was stupefied. It was nowhere to be found, nor did any record of it exist in hospital documents. Some even doubted its presence at St. Elizabeths at all. Dr. Solomon Katsenelbogen, director of research in 1945, recalled talk of the brain but didn’t remember ever seeing it. “If it was studied,” he claimed, “the very meticulous pathologist on staff would’ve made a careful record.”[10] But others were sure of its existence. McKelway testified that he had seen the brain, and St. Elizabeths’ then superintendent Dr. David Harris confirmed that it had indeed traveled to the hospital for research. One thing that everyone agreed on was that its fate had been sealed with Dr. Overholser’s death.[11]

With their condolences, U.S. officials packed up and sent off the known remains of Mussolini’s brain to Rachele in Italy. They arrived in Florence from D.C. in a plain white envelope labeled “Mussolinni.” Despite their bitterness over this spelling error, Mussolini’s family was relieved to finally have (most) all of the body in one place. His eldest daughter, Edda, was especially thankful his postmortem journey had ended. “He had an unusual destiny, my father, even in death,” she said. “His body was shipped like merchandise in a packing crate and his brain in an envelope, like a special delivery letter.”[12] But now the majority of Mussolini was finally at rest. The brain matter that had spent over twenty years across the Atlantic was placed in a box above his tomb, to the right of a large marble bust of his head.

The sample that had once been at St. Elizabeths was never seen again. Whether it was destroyed, stolen, or simply lost in the hospital’s extensive archives will remain a mystery. But a clue as to its existence did appear in 2009, when what were allegedly samples of Mussolini’s brain went for sale on eBay. With a price tag of $22,000, Mussolini’s granddaughter Alessandra[13] believed the samples could be the missing remains that had been sent to D.C.[14] But there was no way of finding out. The seller was anonymous, and based on eBay’s strict policy against selling body parts, the listing was quickly removed. Mussolini’s lost brain matter once again slipped into the realm of the unknown, where it will probably remain forever in the gap between history and hearsay.

Footnotes

- ^ Felix Gillette, “Brain Spotting,” Washington City Paper, 2 August 2002.

- ^ Sergio Luzzatto, The Body of Il Duce, trans. Fredericka Randall (New York: Picador, 2006), 70.

- ^ “Mussolini’s Brain May be Studied by D.C. Experts,” The Washington Post, 31 July 1945.

- ^ “Mussolini Brain, Studied Here, Fails to Explain His Behavior,”Evening Star, 3 November 1945.

- ^ Dr. Haymaker would later go on to study the brain of Dr. Robert Ley, a Nazi henchman who had hung himself in his cell at Nuremburg. His research proved that Ley had a “bad brain” – his cranial lobes had deteriorated, explaining in part his erratic behavior. Basically, Dr. Haymaker accomplished here what Dr. Overholser hoped to prove with Mussolini (Gillette, "Brain Spotting").

- ^ “Man and Evil,” Evening Star, 12 November 1945.

- a, b John McKelway, “Mussolini Brain Here, But Study is Fruitless,”Evening Star, 31 July 1955.

- ^ Luzzatto, The Body of Il Duce.

- ^ Robert C. Doty, “Duce’s Widow Asks Return of His Brain Tissue,” The New York Times, 9 February 1966.

- ^ Orr Kelly, “Mussolini Brain Bits Hunted,” Evening Star, 9 February 1966.

- ^ Nate Haseltine, “Fragment of Mussolini’s Brain Sought in Vain, at St. Elizabeths,” The Washington Post, 10 February 1966.

- ^ “Mussolini Brain Returned With Misspelled Name,” Evening Star, 6 April 1966.

- ^ Fun fact: Alessandra Mussolini is the niece of actress Sophia Loren. Loren’s sister married Benito Mussolini’s youngest son, Romano.

- ^ Nick Pisa, “Mussolini’s ‘brain and blood’ removed from eBay after granddaughter complains,” Daily Mail, 20 November 2009.

![Small Arms Practice Six OSS recruits watch an instructor shoot a small arm during training at Chopawamsic's Area C. [Source: National Park Service]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2A8CB9F8-1DD8-B71C-070E22100840145DOriginal.jpg?itok=xboGo_08)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)