Secrets in the Forest: A Virginia Summer Camp Becomes a Playground for Spies

On a quiet summer day in 1942, a local farmer walking through the fields of Triangle, Virginia approached a wooded area when a rustle of leaves caught his attention. He turned his head just in time to see a blur of movement disappear quickly behind the green foliage. Was it a loose branch shaking in the wind? A deer bounding through the trees? Or… something else? Strange things had been happening in these woods lately. Loud cracks of thunder would break the silence on clear nights, and snippets of German, French, and Japanese could be heard between the armed guards that now lined the wooded perimeter. Wondering if he should take the risk and venture further into the mysterious curtain of leaves, the farmer resolved to make a quick escape instead, looking over his shoulder from time to time, deciding that the secrets in the forest could stay hidden for another day.

In the midst of World War II, the residents of Dumfries, Quantico, and Triangle, in Prince William County, Virginia, realized something big was happening in the woods they knew as the Chopawamsic Recreational Demonstration Area (RDA). Once used as a pyrite mine in the late 1800s, the land became home to summer camp programs catering to low-income families from Washington in the 1930s.[1] The CCC-built cabin camps were segregated by race, however the goal of the Chopawamsic RDA was to provide accessible outdoor recreation activities for all in the D.C.-area. As a “natural playground” in 1936, the Washington Post printed that, “less fortunate children and their mothers of the District of Columbia will find retreat this year for the first time at Chopawamsic...for a two-week vacation in pleasant surroundings in the 15,000-acre tract of woods and streams.”[2]

Back in Washington, President Franklin D. Roosevelt struggled to collect foreign intelligence on the European and Pacific fronts of World War II. Prior to the war, US intelligence organizations were solely focused on domestic issues. The Army and Navy were responsible for foreign reconnaissance, which they were often inefficient in acquiring. As senior diplomat Robert Murphy observed, “It must be confessed that our intelligence organization in 1940 was primitive and inadequate.”[3]

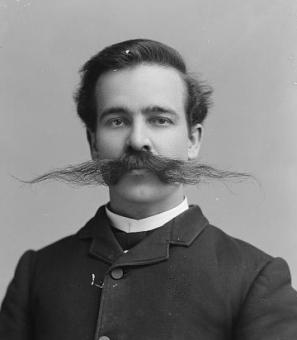

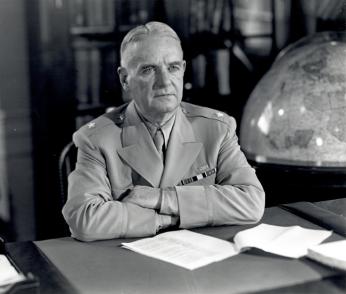

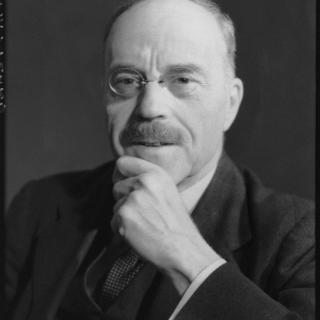

To make intelligence collection more organized and efficient, President Roosevelt appointed William “Wild Bill” Donovan as the Coordinator of Information (COI) on July 11, 1941. A World War I veteran with a Medal of Honor, Donovan used his international experience and exposure to Great Britain’s intelligence agency to develop a new espionage organization under civilian control called the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).[4]

Agents were hired from both the military and civilian sectors for displaying creativity, courage, and specialized skills. Intellectuals, soldiers, con-men, and even future chefs like Julia Child were all recruited to join the OSS ranks...even if they didn’t know what they were signing up for. David Kenney, a student recruit from Wyoming recounted that “They said that we are in the OSS, but they did not even tell us what OSS stood for. They said it is a secret thing. We were not to tell anyone about it.”[5]

On the hunt for a secret place to train his new operatives for dangerous missions, Donovan shared a long wishlist with his realtors. The training center would have to be isolated enough to set off explosives without hurting any residents or attracting unwanted attention, yet also close enough to Washington to communicate vital information to the President. Oh and electricity and running water were “must-haves”, even in the wilderness.

Suddenly, the summer camp infrastructure at the Chopawamsic RDA seemed to be an attractive and adaptable choice. Chosen to host the OSS training center along with its sister park Catoctin Mountain in Frederick County, Maryland, Chopawamsic’s park manager Ira B. Lykes received a letter from the Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, ordering that all resources be placed in the hands of an unnamed organization. Stimson wrote that, “The War program demands that the utmost secrecy be maintained regarding the military use of this property. That fact, or the arm of the service so using this property, should not appear in published Federal Records.”[6] (Incidentally, Chopawamsic wasn’t the only place in Virginia where secret projects were being organized to advance the war effort. Codenamed P.O. Box 1142, Fort Hunt in Alexandria, Virginia was also conducting highly classified operations to acquire intelligence during World War II.)

By April of 1942, OSS recruits began to arrive at Chopawamsic causing rumors to run wild among locals who were now prohibited from entering the forest. Eyebrows raised as sightings of armored trucks and heavy machinery increased and loud bangs disrupted sleep in the middle of the night. Some residents hypothesized that foreign POWs were being held in the park. Ultimately, gossip boiled down to the assumption that military exercises were being extended from the nearby Marine Corps. base in Quantico.[7] For the time being, the OSS presence remained secret.

Classified training videos filmed by Hollywood director John Ford documented what life was like at the OSS camp. Most recruits started their journey on a covered truck that drove in a confusing pattern of loops and turns from Washington to Chopawamsic, completely disorienting anyone onboard.

The first stop in the park was Area A, where students were filmed in their crisp uniforms as an anonymous narrator recounted how: “fresh from offices and laboratories, we leave our real names behind for reasons of security and are given students names which we will be known by for the duration of our training. Names such as Joe, Ben, and Al. Mine was Michael.”[8] Anonymity was key to keeping the training center a secret and the agents and their families safe. Donning their fake identities, trainees didn’t expect to make lifelong friendships as they prepared for covert missions behind enemy lines. Quickly and quietly, the trainees were split up into two camps. Recruits for Advanced Special Operations Training stayed at Camp Area A, while communications students moved to Camp Area C.

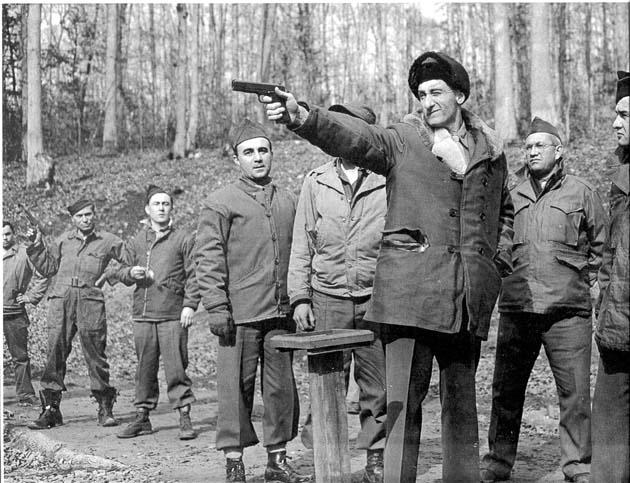

Both camp areas consisted of small log cabins, a main lodge, a dining hall, and administrative offices all outfitted with the newest electronic devices including fridges and dishwashers.[9] Area A was split into smaller camps that included a pistol range, obstacle course and boathouse. At the park’s parachuting school, agents would board a plane on the Quantico Marine Base and parachute into the park, hiking back to the airfield or to the mysterious building known as the “House of Horrors”.[10]

Always engulfed in secrecy, everyone filmed in the training videos wore black masks to conceal their identities, which only added to the spookiness of the “House of Horrors” footage. In the middle of the night, trainees would be awoken suddenly and given instructions to report to the mysterious pistol house. Upon entering the dark cabin, an instructor would give the agent-in-training his problem. The conundrum went something like this: “A group of enemy saboteurs are active in the neighborhood taking a heavy toll of life and property. [You are] to make contact and maintain it until either [you] or the enemy is wiped out.”[11] The trainee would then venture down dark hallways, kicking down doors and shooting at “pop-up” cut-outs of German soldiers meant to test their reaction time and decision making skills.

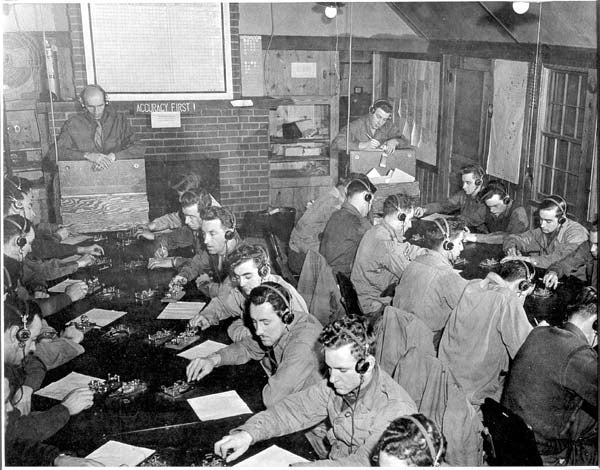

Area C was established as the Communications, or “Commo”, Branch of the training site. Every single OSS agent who worked in communications came to Chopawamsic for training.[12] Over 1,500 people trained at Area C between 1942-1945 developing codes and ciphers and learning short-wave radio, telegraphy, morse code.[13] In Area C, a typical day started with a song. Unlike bugle blasts on military bases, OSS agents were given the freedom to choose their 6:15a alarm, opting for popular hits like “Oh, What a Beautiful Morning,” or “There’s a Star Spangled Banner Waving Somewhere.”[14] Similar to a college or university, trainees had an extensive “course browser” of classes to choose from. Although instead of philosophy or biology, they could register for “elementary principles of explosives”, “lectures on street and house to house fighting”, or “compass problems”.[15]

Whether it was a midnight escapade in the “House of Horrors'' or setting off explosives on abandoned bridges, OSS instructors were dedicated to creating realistic scenarios their operatives might encounter in the field. Designing a tense environment to test survival skills aligned with the OSS training motto: “Hit first and talk afterwards. In short, get tough.”[16]In his training journal, Private Albert Guay reflected:

“Had my first combat training today. Advancing over an open field under fire. Ground frozen and awful hard. Slipped once and banged my kneecap hard. Probably be sore tomorrow. Enjoyed it very much, but it showed me how tough it would be to actually advance under fire. Casualties would be high. We are expendable.”[17]

One of the most elaborate espionage simulations included a trip to Fredericksburg, Virginia, about 25 miles south of Chopawamsic. The mission objective was to infiltrate the local government and sabotage the iron bridge on Route 1 that crossed the Rappahannock River. A team of trainees would show up to the City Manager’s office with a letter forged from the White House, which they would use to gain access to Fredericksburg’s administrative files detailing the town’s water supply, electrical connections, and telephone system.[18]

Equipped with this intelligence, two agents posing as fishermen along the city’s reservoir would stealthy dive into the water in search of their targets. Crawling through a dam, they could gain access to the hydroelectric plant, and mark selected generators with white chalk to indicate that they had been “destroyed”.[19] The simulation was often successful, however the OSS could only duplicate the mock sabotage so many times before Fredericksburg’s City Manager figured out that he was being used and put a stop to the “mission”.

Towards the end of the war, groups of Asian-Americans, primarily Koreans, were brought to Area C to work with the OSS communications system as the US was planning their final offensive strikes in East Asia.[20] After graduating from Chopawamsic, OSS detachments traveled to China and Burma where they were instrumental in establishing intelligence networks against the Japanese.[21] Although not well known by the public, OSS agents and analysts completed operations in the shadows that brought the Allies closer and closer to victory.

Despite all of their successes, the postwar future of the OSS looked grim. OSS leaders argued that their temporary wartime organization should be made permanent to keep the US from falling behind in the race to collect international intelligence as tensions with the Soviet Union escalated.[22] However, Donovan, bored by Washington’s bureaucratic processes, made political enemies that exposed his organization to critics who thought the OSS would become the “American Gestapo” in Washington.[23] The totalitarianism of the Nazi regime was still fresh in the nation’s memory, and Americans wondered how they could ever trust secret surveillance organization. Even President Truman himself feared that OSS would corrupt the United States’ government.[24]

So, on September 20, 1945, President Harry Truman signed Executive Order 9621 which disbanded the OSS and distributed its assets between the Departments of State and War. Donovan gave a farewell address to his organization on September 28, 1945 saying, “We have come to the end of an unusual experiment.”[25]

With only ten days to disassemble the entire agency, many highly trained spies were left dazed and out of work.[26] However, as tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States mounted into a Cold War, the public began to accept the need for a new intelligence agency. In July 1947, President Truman signed the National Security Act, officially creating the CIA. Setting up their offices in the old OSS headquarters on 24th and E Streets NW in Washington, the CIA got to work, recruiting many former OSS agents to join their ranks.[27]

The legacy of the OSS within the National Park Service is still visible today among the trees at Chopawamsic, now called Prince William Forest Park. Visitors can camp in the cabins where OSS recruits lived and hike along the paths where they trained. Who knows...on your next visit to the park, you might just discover a lost artifact or uncover another secret hidden in the woods.

*Special thanks to Chris Alford, Chief of Interpretation, Education, and Visitor Services at Prince William Forest Park for his help with this article.

Footnotes

- ^ Henry Christner, “Public Park, Private Past,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, January 29, 1995.

- ^ “Capital’s Poor Folk To Go Camping Soon: Beautiful Chopawamsic Area Is Being Prepared as Vacation Site for Underprivileged Children and Their Mothers.,” The Washington Post, April 19, 1936.

- ^ Master Sgt. Matthew J. Morrow, “Office of Strategic Services Revolutionized American Warfare,” Association of the US Army 65, no. 1 (January 2015): 53–55.

- ^ National Park Service, “Office of Strategic Services (U.S. National Park Service),” December 16, 2015, https://www.nps.gov/articles/office-of-strategic-services.htm.

- ^ Chambers II, OSS Training in the National Parks and Service Abroad in World War II, 2008.

- ^ John Whiteclay Chambers II, OSS Training in the National Parks and Service Abroad in World War II (Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Park Service, 2008).

- ^ Chris Alford, Interview with the Chief of Interpretation, Education and Visitor Services at Prince William Forest Park, interview by Dominique Mickiewicz, August 3, 2021.

- ^ John Ford, OSS Training Video, 1:12-1:30, https://www.nps.gov/media/video/view.htm?id=53C70DAA-B910-F8A8-56C7C44A….

- ^ National Park Service, “Office of Strategic Services (U.S. National Park Service),” December 16, 2015.

- ^ Alford, Interview with the Chief of Interpretation, Education and Visitor Services at Prince William Forest Park.

- ^ John Ford, House of Horrors, 0:20-0:35, https://www.nps.gov/media/video/view.htm?id=53E9FA2B-B372-99D6-C53519DE….

- ^ Alford, Interview with the Chief of Interpretation, Education and Visitor Services at Prince William Forest Park.

- ^ National Park Service, “Office of Strategic Services (U.S. National Park Service),” December 16, 2015.

- ^ Chambers II, OSS Training in the National Parks and Service Abroad in World War II, 2008.

- ^ Chambers II.

- ^ John Ford, Obstacle Course, 0:23-0:26, https://www.nps.gov/media/video/view.htm?id=53DD6E27-B8D8-004F-38CBA4F2….

- ^ Chambers II, OSS Training in the National Parks and Service Abroad in World War II.

- ^ Christner, “Public Park, Private Past,”Richmond Times-Dispatch, January 29, 1995.

- ^ Chambers II, OSS Training in the National Parks and Service Abroad in World War II, 2008.

- ^ National Park Service, “Office of Strategic Services (U.S. National Park Service),” December 16, 2015.

- ^ Morrow, “Office of Strategic Services Revolutionized American Warfare,” Association of the US Army 65, no. 1 (January 2015): 53–55.

- ^ “Establishment of the CIA,” Harry S. Truman Library, https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/education/presidential-inquiries/establis….

- ^ Chambers II, OSS Training in the National Parks and Service Abroad in World War II, 2008.

- ^ “Establishment of the CIA,” Harry S. Truman Library, https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/education/presidential-inquiries/establis….

- ^ Morrow, “Office of Strategic Services Revolutionized American Warfare,” Association of the US Army 65, no. 1 (January 2015): 53–55.

- ^ Chambers II, OSS Training in the National Parks and Service Abroad in World War II.

- ^ John Whiteclay Chambers II, OSS Training in the National Parks and Service Abroad in World War II (Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Park Service, 2008).

![OSS Suitcase Color image of a brown suitcase on display at Prince William Forest Park's Visitor Center. The objects inside include the OSS Weapons Manual (1944) and two silk maps of China's rivers and railways developed by the recruits at the Chopawamsic training site. [Photo Credit: Dominique Mickiewicz]](/sites/default/files/styles/embed/public/Suitcase%20Final.jpg?itok=8O3apSpS)

![OSS Suitcase Color image of a brown suitcase on display at Prince William Forest Park's Visitor Center. The objects inside include the OSS Weapons Manual (1944) and two silk maps of China's rivers and railways developed by the recruits at the Chopawamsic training site. [Photo Credit: Dominique Mickiewicz]](/sites/default/files/Suitcase%20Final.jpg)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)