The Rise and Fall of the Washington City Canal

Just within sight of the Washington Monument is a little stone house not open to the public. Used for National Park Service storage today, this house is the last remnant of one of the biggest mistakes in municipal planning in the District’s history: the Washington City Canal.

The canal was first conceived of by architect Pierre Charles L’Enfant. He envisioned something grand like, well, the Grand Canal at Versailles. George Washington thought the canal was a good idea because it would increase commerce by bringing goods directly into the city center.

But, right from the beginning, the proposed canal was plagued with problems. Two fundraising lotteries in 1796 were a “dismal failure.” The first managing company, the Washington City Canal Company, went under in 1809 with little less than a mile completed. The succeeding canal company estimated $100,000 would be needed to complete the project, but only raised half that amount by 1810. They still threw a party in May of that year to break ground. President James Madison symbolically opened the event and a good celebration was had, everyone apparently ignoring the low possibility of success.

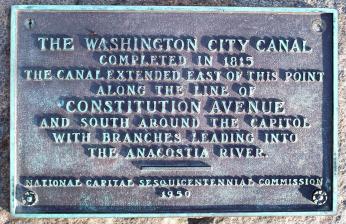

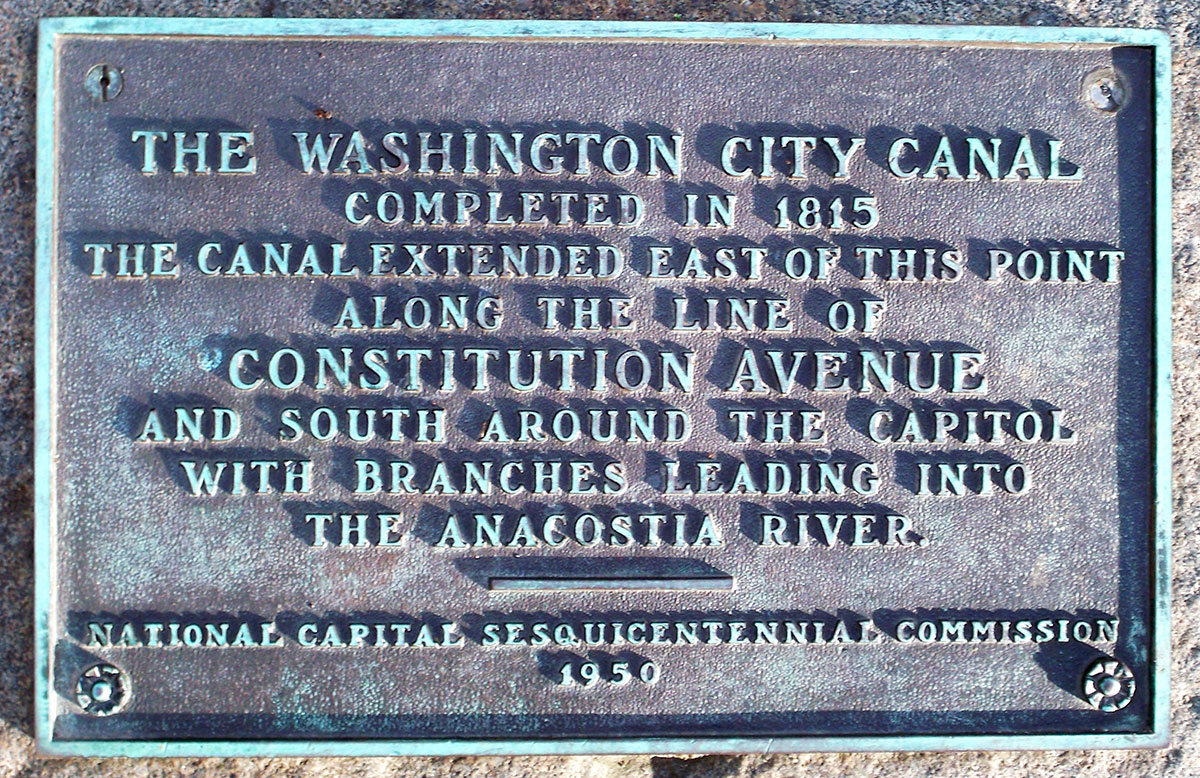

Although the company never managed to raise the full amount, and the War of 1812 halted construction, the Canal formally opened in November of 1815. Barges with a marine band and distinguished guests inaugurated the event by traveling the length of the canal from 12th and B St, N.W., to the Eastern Branch. Despite the hopeful parties, the remainder of the canal’s history was a disaster.

Most larger boats could not travel on it because it had only been cut three feet deep. This made its stone walls, built to accommodate the steamboat travel that would never fit, more than “slightly ridiculous.”[1] Well, perhaps that problem wasn’t such a big deal, right? Initial crafts were little more than rafts, but after the Canal was connected with the (much more successful) Chesapeake and Ohio Canal in 1833, the impressive barges of the American Canal era made their appearance. And then there was the other problem with the Canal: no one had accounted for the tide. At high tide the Canal threatened to break banks and flood parts of the city; at low tide, long stretches of the Canal were unusable.

Overall, the construction of the Canal was a bust, but it only got worse. Silt from erosion began to collect in the trench, and Washington City citizens, this being years before garbage collectors, threw all sorts of garbage and unmentionables in the canal. It became by 1860 “a canal only in name [and] a open municipal sewer by use.”[2] The most traffic the canal ever got in later years were the cows who frequently fell in and had to be rescued.

Most of the canal was filled in in the 1870s and 1880s. By the 20th century, not a sign of the old waterway remained. Very likely the city wanted to forget it as soon as possible. The last trace, the stone building, is the former home of the lockkeeper who managed the canal’s extension into the C&O canal. The unassuming building, mostly overlooked by tourists skirting the Washington Monument, is itself a monument to the city of Washington, and its early failures in city planning.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)