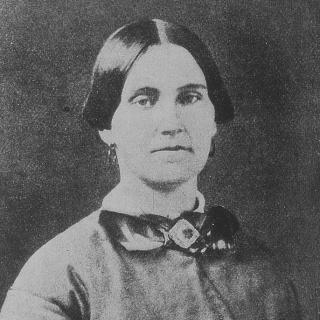

Kate Chase: Washington's 19th Century Supreme

In the second half of the 19th century, Kate Chase (1840-1899) was known the country over as the most beautiful and influential woman there ever was in Washington. She occupied the most powerful position in Washington society that a woman could hold, and held sway far beyond her gender. A National Tribune article from 1898, a year before her death, called her life the history of the Civil war itself, stating:

"No one woman had more to do with influencing the movements on the military and the political chessboard than she, and it was her influence largely that kept McClellan at the head of the military.”[1]

Kate Chase’s role in Washington and the Civil War was partly due to the position of her father, Salmon P. Chase, the Secretary of the Treasury. Because Salmon was without a wife when he was appointed in 1861 by Abraham Lincoln, Kate was her father’s official hostess, a position she had held since she was 15 when her father was Governor of Ohio.

As the hostess for the Secretary of the Treasury, Kate would traditionally have been only the third most important lady in the district. However, the number two spot was vacant because Frances Seward, the wife of the Secretary of State, was ill and withdrawn from society. The supreme of Washington still should have been the First Lady, but the awkward Mary Todd Lincoln was no match for the secretary’s daughter.

Here are just a few things people had to say about young Kate:

"[She was] cultivated to her fingertips, she had the manners that come from exquisite breeding and a charming heart, and had been, all through her father’s public career, a daughter of whom any could be extravagantly proud."[2]

"[She is] full of intelligence and knowledge. Her figure is tall and slight, but at the same time beautifully rounded; her neck is long and graceful, with a sweet pretty brunette face. I have seldom seen such lovely eyes and dark eyelashes; she has rich hair in great profusion, but her style and dress were of the utmost simplicity and grace."[3]

"The most brilliant woman of her day. None outshone her."[4]

"When she is talking to you, you feel that you are the very person she wanted to meet. That she has forgotten your existence the next moment is an afterthought."[5]

Mary Todd Lincoln tried to exclude Kate by forbidding her husband from dancing with her or even talking to her. But whether the young lady talked to the President or not, she still had the ear of her father, the most prominent statesmen of the day, and several military generals.

Kate’s activities didn’t stop at the parlor door. In the 1860s, Kate functioned as her father’s private secretary. In the elections of 1864 and 1868, she was “consistently referred to as her father’s campaign manager.”[6] Her efforts to put her father in the White House were viewed by many as a move to put herself truly at the peak of society but she denied these assertions in an 1893 interview, saying simply: “I was anxious that my father might be president in order that he might carry out his ideals.”[7]

After her father moved from the Cabinet to the Supreme Court, Kate remained the belle of Washington. During the impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson, she appeared in court every day to observe her father oversee the proceedings, and “others competed for tickets to see her.”[8]

For a woman who’d known such bloom in her life, how did she end up dying in poverty in 1899? Well, in 1863 Kate Chase made what writers would later call “the greatest mistake of her life.”[9] She married the rich and handsome governor of Rhode Island, William Sprague. Their wedding was the wedding of the year, if not the decade. The guest list numbered at least 600 and the gifts were said to be worth “nearly one hundred thousand dollars.”[10] The wedding march was specifically written for the occasion and President Lincoln was in attendance (Mary Todd was not).

Sprague’s fortunes disappeared in the early 1870s, and it might have been around the same time that his good nature disappeared, too, and he took to drink. There were whispers in the papers that Kate was having an affair with a senator from New York, Roscoe Conkling. The situation exploded in 1879 when Sprague, in a rage, chased Conkling out of the house with a shotgun.[11]

Kate was awarded a divorce in 1882, and the court returned her maiden name — which the press had always continued to call her anyway. She retired to her family estate, Edgewood, on the outskirts of Washington. Although in poverty and peddling vegetables to make ends meet, Kate retained the friendship of prominent Washingtonians. Friends arranged mortgages for Edgewood and an allowance for the former belle.

1899, nine years after the suicide of her son, Kate Chase breathed her last at the age of 58. From the highest peak of national society to poverty and eventual obscurity, Kate Chase joined the ranks of Washington stars that burned “twice as bright and half as long."

Footnotes

- ^ The National Tribune. (Washington, D.C.), 17 March 1898. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ A woman who met her in 58. “William Sprague Papers” Rhode Island Historical Society.

- ^ Diarist Isabela Trotter. “William Sprague Papers.

- ^ From The Washington Star. Chiaverini, Jennifer, Mrs. Lincoln’s Rival.

- ^ Ex secretary McCulloch. The Evening Times. (Washington, D.C.), 21 Feb. 1896. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ Aynes, Richard L, “Kate Chase, the Sphere of Women’s Work, and Her Influence upon her Father’s Dissent in Brawell v. Illinois,” Ohio History, 117, (2010).

- ^ Carpenter, Frank G, “Kate Chase chats about…,” Los Angeles Times, 15 Oct. 1893.

- ^ Caroli, Betty Boyd. First Ladies: Expanded Edition. (Oxford University Press: 1995) 56.

- ^ Carpenter, Frank G, “Kate Chase chats about…”

- ^ Evening Star. (Washington, D.C.), 12 Nov. 1863. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ "A Famous Beauty." The Argus. (Holbrook, Ariz.), 21 Oct. 1899. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)