The Oldest Profession in Washington

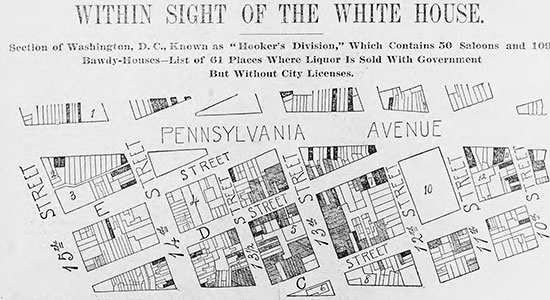

Not to cast any doubt on the virtue of our historical statesmen, but for the latter half of the 1800s, at least two major red light districts were right in the center of D.C., even “within sight of the White House.”[1]

One of the most notorious of these was Hooker’s Division, on the west end of the federal triangle and right on the National Mall. With the White House to the north, the Capital to the east, and the business district within walking distance, it was pretty perfectly positioned. The area got its name during the Civil War, when Union General Hooker moved everything seedy in the capital to a choice few spots and The Division was one such place.[2] The name also at least partially arose from how often Hooker’s men visited the district (hint: a lot). The Evening Star had this to say of Hooker’s Division in 1863:

There are at present, more houses of this character [ill-repute], by ten times, in the city than have ever existed here before, and loose characters can now be counted by the thousands.[3]

After the end of the Civil war, business returned to the normal ebb and flow of the seasons –that is, with the rhythm of congressional sessions. Things remained relatively quiet until the end of the century. Until the 1890s, Hooker’s Division was mixed residential and commercial area, with native-born white and black citizens as well as European immigrants. With the high-wheeling corruption and extravagant spending associated with the Gilded Age, business was booming again. By 1900, most of the buildings in the Division were brothels and the number of sex workers registered in the area increased significantly.

The nature of the work also changed over time. Earlier, most sex workers were their own bosses. They rented rooms in boarding houses, found their own clients, and kept all their wages. But capitalism took hold of the sex industry as well as it did the rest of America. By the end of the century, most sex work took place in brothels managed by a madam.

One such madam of note was Mary Ann Hall, who managed one of the “upper ten,” the fanciest and most discreet brothels in the city in the 1860s. Hall’s brothel was located in “Louse Alley,” a red light district located where the National Museum of the American Indian is today.[4] Hall and her brothel did very well as evidenced by what they left behind. A recent excavation of the site of the three story brick house turned up imported bottles of French Piper-Heidsieck champagne, which today would be worth “between $1,000 and $5,000.”[5] Upon her death in 1886, her estate was valued at $100,000, or $1.9 million in today’s dollars. You can still visit her imposing grave today, in the Congressional Cemetery.

Though it might seem counter-intuitive, establishments like Hall’s offered an attractive option for some women in Washington. Given the scarcity of factory jobs (D.C. was never a big industrial center) and low wages for work that was available, women here had fewer opportunities than their counterparts in other cities.

But life in a brothel could be comfortable. In sex work it was possible to have regular meals and good food, fancy household furnishing, servants, and good clothes. And that’s without mentioning the possible influence these women had on national policy. Although it cannot be confirmed, one expose from 1883 had this to say about the lobbying of sex workers from the Senate balcony:

From this flattering perch, they become objects of unctuous admiration, displaying to excellent advantage their gorgeous apparel with half revealing monuments of maternity peeping over brilliant bodices, and arms dressed in rouge the helps nature amazingly.[4]

But it was not to be forever. The red light districts closed down in the Progressive Era that followed the Gilded Age. Senate hearings about sex work in the city in 1912 and 1913 led to the 1914 banning of these houses of ill-repute. The police cracked down and the sex workers and madams left their establishments. In the 1930s, Louse Alley, which had eclipsed Hooker’s Division as the worst den in the city, was razed to the ground and the area was converted to public park land.

Sources:

Seifert, Donna, “Within Site of the White House: The Archeology of Working Women,” Historical Archeology 25.4, (1991).

Footnotes

- ^ “Within Sight of the White House.” Library of Congress.

- ^ "Rough-and-Tumble Lost Neighborhood of Murder Bay," on Ghosts of DC. Accessed 3 June 2015.

- ^ Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 27 Oct. 1863. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- a, b O’Brien, Elizabeth Barthold. “Illicit Congress in the Nation’s Capital: The History of Mary Ann Hall’s Brothel.” Historical Archeology, 39.1 (2005): 47-58.

- ^ “Madam on the Mall.” The Smithsonian.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)